(Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 - UMR SENS (Savoirs ENvironnement Sociétés))

Undoubtedly in spite of herself, María Sabina, a Mazatec shaman1 from the town of Huautla2 in the Sierra Madre Oriental in Mexico, traveled around the world. As a poor, illiterate Indian woman who died destitute in 1985, at the age of over eighty, she obviously rarely actually left the mountains except for occasional trips to Oaxaca or Mexico City. Through writings, films, photos, and paintings, however, her image, her chants, and the vicissitudes of her life, crossed many international borders. Traces of the shaman thus traveled through time and across space, weaving an intricate web of meanings and representations around a glorified image of the shaman that ranged from esoteric, psychedelic, mystical, and ethnic to political, social, literary, and artistic.

As the image of María Sabina gained this level of multivariate circulation, however, its meanings were also inevitably eroded by mechanical reproduction and marketing. She can be found being marketed alongside other representative icons—such a Che Guevarra--of forms of “eclectic wisdom” attributed to Mexican and Latin American cultures3. Images of the shaman have been duplicated, purified, and reduced to photographic prints or stylized portraits that are available for a wide variety of audiences and uses. The assemblage of imaginary projections projected by standardized copies offers an idea, reduced to its simplest form, of resistance to conformity and the rationality of the modern world. The goal of this article is to examine this nebulous opposition, of which the shaman María Sabina became the source, in order to identify pivotal moments in the creation process of creating the partially anticolonial4 narrative and protests—however “suitable” and “authorized”—that shaped her symbolic capital as a figure of protest and resistance.

Despite the fact that María Sabina has often been cited as proof of the persistence of an original, primeval world, she is most definitively not a timeless figure. Her past, and the principal phases of its fabrication, can be investigated, as can the back-and-forth process between various references and factors surrounding its endlessly renewed discovery. In order to navigate these diverse discursive spheres, this article borrows certain principles from the analysis of “social iconology” defined by Jean-Claude Chamboredon5 to approach photographic, cinematographic, and literary forms that become collective symbols, with a specific focus on the “conditions of their fixation and interpretation”6. Historicizing the figure of the shaman leads to “browsing” among the successive instantiations of meaning that they distill by examining them according to the principal socio-historical contexts that motivated them, while also identifying the photographers and authors who integrated her into their own life stories.

As an heiress of ancestral rituals and “archaic” language, María Sabina’s itinerary was unique not only in Mexico, but also in terms of her relations with the outside world—and most significantly, the United States. Her iconological and literary—but also touristic and political--path suggests the use of a historical definition of the notion of primitivism, in addition to a “reterritorialization” of the notion through a close reading of dialogues between “Western and extra-Western” authors7. How did the heroization of a “primitive” figure become transformed into images of a marginalized woman, a victim, a resistance fighter, or even a combatant? How did María Sabina come to represent different chronological periods, including both precolonial and postcolonial eras? What discursive and iconographic rhetorical devices contributed to the development of the intensity of her image, which has become memorable and persistent in such a wide variety of patrimonial, political, and touristic domains?

A Romantic Exploration

As the center of a veritable “discursive explosion”8 in the 1960s, “the sage of the sacred mushrooms”9 initially personified--and bore witness to--the mystery of an ancient world. The narrative follows a familiar pattern10. The “primitive Indian” belonging to one of the “tribes that are most remote from our culture”11, was “discovered” by Gordon R. Wasson, a New York banker who was passionate about mycology and who in 1957 published a summary of his shamanic encounter in Life magazine. In his words, the purpose of the project was to “scrutinize the most intimate religious secrets of this remote people!”12 The story in Life was accompanied by photographs of the ritual taken by Allan Richardson, a photographer from the New York Historical Society13. Transcriptions of her chanted rations, the high point of the story, were made available on a record album issued concurrently with the article’s publication14. Her voice, her words in Mazatec--and the translation that penetrated the enigma, and the description and accompanying photographs of the ceremony resemble pieces of a puzzle that showed the shaman in action. They also established the basic arguments that identified her, as a Mazatec healer, but also as a witness and archetypal mediatrix who possessed the ancestral secrets of “another world”15.

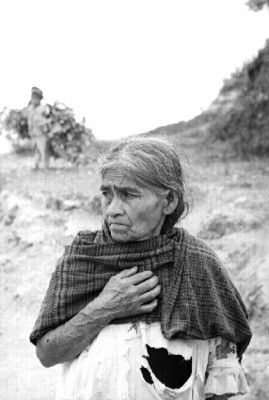

Fig. 1 : Alan Richardson, Huautla, 1958

Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann, Les Plantes des Dieux, Paris, Les Éditions du Lézard, 1993, p. 153.

It is important to emphasize the fact that Wasson was not alone in his quest, which took place at a time when shamanism was about to become a global phenomenon and the focus of tension between fascination with anti-modern practices, as well as an escape for Westerners seeking the interstices of globalization16. The myth of an archaic secret buried in the folds of History and surrounded by the sulfurous halo of mystery is assuredly not new17. The duality of dissemination and discovery that structures this myth is among the orientations adopted as early as the eighteenth century by literary modernity, when the desire for knowledge stimulated a kind of economy of secrets and revelations. The configuration of the creation and reception of this paradigm, i.e., ways of interpreting or indicating it, was in any an established historical phenomenon18. The banker/explorer Wasson thus revealed the story of the phases of his discovery of María Sabina, cultivating the idea of the revelation of a powerful enigma, like an archeologist excavating an antique treasure and deliberately unveiling it using a series of gestures19.

A notable extension of the fascination of shamanism as a romantic inversion of Enlightenment rationality underlies this rhetoric of the discovery of secret treasures of archaism20. Indeed, this is the same rhetoric that provided the iterative value of Wasson’s project, in which the quest for the secrets of the Other intersected with the discovery of the Other in oneself through the shamanic experience. In addition, the social and political context of the 1960s and 1970s clearly influenced this economy of revelation through experience and revelation. Wasson’s discovery had a particularly powerful impact in Mexico because it became indirectly associated with—and not by chance—the crisis of the Mexican government in the 1970s, as well as transformed by indigenist and anthropological literature.

At the Margins of Anthropology

Wasson’s article, which also appeared in the Spanish-language edition of Life, quickly appeared in other publications. He had essentially created a new, hybrid genre that merged journalism with literature and anthropology. Other writers who defied genre boundaries, including Gutierre Tibón and Fernando Benítez, appropriated Wasson’s discovery, reaching still wider audiences21. In addition to a number of articles about the shaman and her sacred mushrooms, beginning in 1964, Benítez published Los Hongos Alucinantes, embellishing Wasson’s primitivist rhetoric and giving a starring role to María Sabina and linking her to other shamans, whom he described as “nearly extinct saints and heroes” from a “savage world”22.

Interestingly, writings about the shaman and sacred mushrooms remained on the margins of Mexican academic anthropology. Wasson, a banker by profession and a self-taught mycologist, was able to involve a number of well-known scientists23, but the discovery of the shaman nevertheless remained largely outside the scope of academic research. The French anthropologist Guy Stresser-Péan was referenced in the Life article, however, although he appeared only in the background of a photograph of the ceremony and participated minimally to the written account of the ceremonial experience24. Similarly, with the exception of a chapter by Claude Lévi-Strauss25 concerning the epistemic project implied by Wasson’s “mycology,” and despite Wasson’s numerous literary and journalistic publications about Huautla, he was seldom mentioned in the ethnological literature.

Indeed, the advent of this “dubious tourism,” as the indigenist anthropologist Carlos Inchaustegui called it26, was treated with scorn in most Mexican academic circles27. Beginning in the 1970s, hybrid writings about Huautla that blended chronicles with personal narrative, history, archeology, and anthropology were scientifically assessed: “Literature or anthropology?” inquired Andrés Médina28. Médina found Benítez’s work chaotic and uncategorizable in spite of his “claims to offer ethnological interpretations”29, primarily as much due to his ideological position as his methodological oversights. Médina, who worked for the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia (ENAH) at the time, called attention to the journalist’s romantic vision that reduced the Indians to a static, neolithic state of immutable perfection30. His denunciation of Benitez’s primitivism, tinged with a combination of nationalist ideology and indigenist rhetoric, was slightly tempered by his discussion of Benitez’s journalistic contribution by presenting himself as “a liberal journalist with the healthy and simple intention of denouncing a social problem in which corruption and exploitation predominate”31.

There are several weaknesses in Benitez’s work on the Mazatec, and specifically on María Sabina. First, echoing Wasson’s attitude, he projected his own Manichean apologia for primitivism onto María Sabina. Second—and relatedly--Benítez used the exploration of the ceremonial hallucinogenic experience to gain privileged access to the Other’s knowledge, discrediting him among academic anthropologists. Finally, the focus on the social context that he inherited from the indigenist literary tradition indirectly tainted his portrayal of the shaman, whose life he portrayed as a spiritual path lined with challenges. He depicted the shaman’s ancestral – and precolonial – wisdom against a background of misery and victimization, but also of virtue, that of an “unblemished, immaculate woman” “of rare morality and elevated spirituality”32.

Political Protest and Literary Innovation: The Author-Witness

The aura of primitivism around the shaman that Masson helped generate reinforced her image as an authentic witness from the “other world.” Relayed by Benítez, this idealized vision resonated in 1970s Mexico, when post-Revolution plans for economic and social progress included policies intended to integrate indigenous minorities that were struggling for legitimacy. Plans to homogenize the Mexican population by “mixing” the Indians through a process of Hispanicization and “whitening”—in an approach that was racial as well as cultural and linguistic--were the subject of harsh criticism33. As Claudio Lomnitz observes, older, more epic visions of revolutionary nationalism later gave way to more personal narratives centered on artists such as Frida Kahlo and new literary experiments by authors such as Elena Poniatowska and Carols Monsiváis34. These writers adopted a novel narrative voice that resembled chronicles and testimonials in order to “recover the silent voices of the dispossessed” of internal colonialism35.

The historical circumstances under which María Sabina was elevated to the status of an archetype greatly contributed to her oppositional symbolic capital. Amid the turbulence of the 1970s and the affirmation of countercultures around the world, and against the backdrop of conflicts related to the Vietnam War, María Sabina came to symbolize resistance to the global grip of North American conformism36. The climate of protest was at its peak in Mexico, coinciding with the rejection of the policy that sought to bring about the integration of Indian minorities, initially through social movements with demands that were increasingly ethnically centered37, and later by a new generation of anthropologists who were deeply critical of a strand of applied anthropology that supported cultural assimilation38. Paternalistic policies seeking to integrate Indians were described as promoting “de-Indianization”39. As a counterpoint to assimilationist objectives and the anthropology that supported it, Wasson’s discovery thus appealed to Indianist opponents and writers inspired by non-academic anthropology who sympathized with neo-Indian and New Age trends--an echo that was continually repeated.

Bonds that developed between students protesting in several Mexican universities and Mexican intellectuals, artists, writers, and cultural press journalists played a key role in legitimizing the student movement40. The 2 October 1968 massacre by the Mexican Army during the protest in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco was the tragic culmination of this movement. Published a scant twenty days after the event, a supplement to the cultural journal Siempre! entitled “Cultura in México”41, was a milestone in the denunciation of the government’s bloody response to the protest. Fernando Benítez, who had already published his book on the discovery of María Sabina, wrote a solemn article, “Los días de la ignominia” [Days of Ignominy]42, bitterly condemning State-sponsored repression, conservative Mexican culture, and a corrupt society. The social movements of the period also fostered a cultural effervescence that fueled a widespread, eclectic artistic and cultural phenomenon called la onda [the wave]. Amid this climate of social protest and literary, musical, and cinematic innovation, María Sabina and her sacred mushrooms represented a source of inspiration for a social resistance movement, against a background of emergent, holistic, neo-Indian ideas, psychedelic experiments, and the drama of Tlatelolco raised as a symbol of revolt43.

The period was an outgrowth of crises during which the “crystallization of esthetic and political debate around question”44 and artists’ commitments to social struggles was accompanied by creative abundance in a variety of media. Within this context, the Andrés Medina’s critique decrying the impossibility of situating Fernando Benítez is understandable. Neither literary nor anthropological, Medina described his writings as “constituting a kind of pamphleteer literature that simulates scientific essays, [either] literary work or political complaint”45. Indeed, this intermediate position as an uncategorizable writer could also describe of a number of other emerging writers at the time. This illustrates Jean-Claude Chamboredon’s argument that the “conceptualization of cultural systems as configurations of places and jobs” “led to the reconstruction of the individual situation as a collection of positions.” Chamboredon proposed the concept of “crystallization of status” as a way of modeling “the representation of social position as a structure of positions in different dimensions”46.

In simultaneously functioning as a journalist, an anthropologist, a writer, a publisher, a historian, and a professor, Benítez clearly participated in this genre-mixing process47. He did not have a monopoly on accumulating job descriptions, however, although while publishing his work, he also began authoring chronicles and a language of memory, a literary genre also that served as a substitute for historiography, filling the void concerning the Tlatelolco massacre in official history48.

There was a noticeable rise in the number of hybrid texts “between novels, testimonials, and journalistic investigations,” also furthering their writers’ critical purposes. One example of this authorial turn was Elena Poniatowska’s emblematic book, published one year after the student massacre, La Nuit de Tlatelolco. Témoignages d’histoire orale. Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero49 notes that Poniatowska used narrative techniques that rendered her text “polyphonic” in the Bakhtinian sense, an idea later adopted by “postmodern” anthropology50 because of its critique of historical cultural totalization. Beyond the plurality of autonomous voices, “heroes” did not serve simply as objects, but as “discursive subjects”51.

The discursive construction of María Sabina reflects this pivotal period, when post-1968 literary inventiveness intersected with a trend towards writing that concentrated on memory, protesting against prevailing academic anthropology, and political denunciations of the fragmentation of marginalized populations in Mexico, including Indians. Undoubtedly unbeknownst to her, the shaman served as a reference in the 1970s controversy that criticized anthropology by insisting that Indian populations had the right to cultural difference. In 1969, for example, the cultural journal that Benítez founded, Siempre!, featured an interview with the “the world’s most renowned shaman, a victim of anthropology and irresponsibility”52. This “woman-shaman” incarnated the virtues of the “the culture of resistance” among the Mexican population that Guillermo Bonfil53, an anthropologist involved in the 1970s protests who opposed against Mexican national elites and their civilizing project in the 1990s. The mediator of precolonial “ancient hymns” was then invented as the concretization of this invisible Mexico (for the authorities), which was peopled by “those who resist rooted in forms of life of Mesoamerican origin”54 despite the yoke of the dominating classes.

The Time of the Word

By distributing recordings, transcriptions, and translations of her chants, Wasson thus led the way in deciphering of the shaman’s discourse. There were a number of incentives for the interest in her messages, both within the new Mexican anthropology, which sought to reconsider the Indian perspective, and new hybrid literary work using a politically committed “I-witness”55. Arguments that María Sabina was a source of a different way of knowing effectively contributed to a broader transformation that gradually replaced the integrationist paradigm with a multicultural approach.

Unlike classical indigenist literature, the shaman was framed within her irreducible alterity, which had been transmitted despite centuries of “Westernization” and colonial domination. Fernando Benítez and a variety of fellow authors who published their experiences promoted another means of gaining access to this knowledge through ceremonial and experiential learning, facilitated by hallucinogens56. María Sabina, mediator through ecstasy, was perceived as the crucial link to an expanded archeological past that possesses a subterranean, secret language that resonates in the present as a faithful echo of the pre-Hispanic world from beyond the tomb because it enables its vestiges to resonate and express themselves57. The sacred mushrooms thus provide an experience that channels the past through the body. The shaman incarnates this past, a conduit for memories that reached back to their origins: “Her expressive face glowed, reflecting the mysterious light of that first inebriation, so remote in time but still so alive in memory”58.

Asked to transpose the past into the present through the effect of the hallucinogens and her ritual chanting, so often recorded in experimental writings, she enacted a different relationship with the past, while, as Myriam Hernandez Reyna has shown59, a new system of national historicity was established based on the “memorialization of history.” It is no coincidence that the discursive explosion surrounding the shaman and these chants and ecstatic experiences emerged in the 1960s, when memory was an important resource for a postcolonial process that pursued “an interest in finding ‘subaltern’ world views, memories made by colonial system of knowledge production”60.

In addition to narratives of the ecstatic ceremonial experience, this was a case of the shaman as a source of words and knowledge from the postcolonial past. Her voice is not exclusively described as emanating from the distant past, however. From the perspective of hybridization of registers, innovations that collide with certain canons of indigenist literature are included in its contributions. The broad outlines of this literary form can be observed, as Reyna affirmed in the so-called “Chiapas cycle”61, whose authors drew on specific characters to recreate Indian reality and describe customs and daily life while also voicing a critical perspective on social inequalities. The passage written by Benítez about the “Life of a Mazatec Woman”62 presented the shaman through the prism of social realism, echoing critical indigenist literature about Indians relegated to the margins of economic development.

Seen in this way, it was clear that the shaman was not exclusively perceived as representing precolonial antiquity. Alongside her representations as atemporal in the ceremonial setting, she was also framed as a contemporary to the author-witness, thereby emphasizing the singularity of her own presence as an indigent Indian woman. This sharing of time with the author is reinforced by dialogic writing that presents the shaman as an interlocutor. In using this narrative process, the author positions himself as if not equal to, co-subjective and engaged with other subjects whose points of view he describes alongside his own. This assumed horizontality is relative, however, as Benítez focuses a significant proportion of his narrative on his own experience. He also regretfully underscores the limitations of their exchanges due to the lack of a shared language: “Unfortunately, the fact that María Sabina speaks only Mazatec prevented me from getting to know her in her complete richness and spiritual depth”63.

The Native Point of View: The Life of a Woman-Spirit

The discovery of María Sabina’s private life in the wake of Wasson’s initial “discovery” through Benitez’s revelations unfolded in the pages of the most successful adaptation of her narrative, transcribed and translated from the Mazatec by Álvaro Estrada, also a native of Huautla. Initially published in Mexico in 1977 as Vida de María Sabina, la sabia de los hongos64, the book was so internationally successful that it reached fourteen editions65. After Wasson and Benítez, Estrada’s intention was to act as a mediator who portrayed the shaman’s point of view and removed the focus from her ceremonial function. María Sabina’s story takes the reader beyond her fame and provides the details about her personal history. We read about her life as an indigent person, her unhappy marriages, her periods of mourning, her daily life, her work as a healer, and how she viewed foreigners and outsiders. Álvaro Estrada’s contribution unquestionably foreshadowed the arrival of a new figure on the scene, the “indigenous ethnographer,” as James Clifford called them in reference to the Negritude movement66. Indeed, Estrada’s legitimacy as author/intermediary derived from the fact that he shared his subject’s community of origin, and specifically her language community. His ethnographic work was also the product of a writing and publishing pact, however, encouraged by hybrid genres amid the protest-rich environment of the times, as mentioned earlier.

Álvaro Estrada, who was also worked a journalist in Mexico City, derived his editorial legitimacy from contacts and by circulating his project among a number of mentors. They included colleagues at the cultural journal Siempre!, where he worked on occasion, who reportedly suggested that he record the shaman for publication. Álvaro Estrada spontaneously expressed his reservations about such a project, which he feared would be exceptionally difficult because it followed the work of Benítez and Wasson. He “authorized” himself to do so by admitting that María Sabina “has not been entirely understood by those who had revealed it to the world”67. This admission, it is worth emphasizing, reveals the extent to which his undertaking appears to respond to the frequent ellipses in Benítez’s writings, whose partiality was scarcely acknowledged because of an inability to understand her native language.

Based on interviews conducted and recorded, the text was also translated into Spanish by Estrada. It was subsequently forwarded to Wasson in 1975, who in turn submitted it to Octavio Paz, who made editorial changes. Journalism, anthropology, mycology, poetry combined to again fuel hybrid genres in which intermediaries between María Sabina and the world collaborated with her. This creative pact with the shaman confirmed an image initiated by Masson, the amateur mycologist, and extended by Estrada, a Mexican journalist68. The result was that María Sabina functioned as an archetypal source of the language of the Other that would later become the basis for a variety of poetic experiments.

The resulting texts contrast with other publications surrounding the shaman. The author-ity of the I-witness and author-middleman is the product, not of scholarly or literary erudition (as was the case with his mentors), but of a shared “horizon of alterity”69. The narrative process, which benefited from Octavio Paz’s editorial assistance, was indeed quite different from Benítez’s approach. In this regard, Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero70 highlights the textual contrast by analyzing the two authorial figures: Fernando Benítez, who is highly present in the narration, reveals his lack of familiarity with María Sabina’s culture while suggesting ethnocentric interpretations. Álvaro Estrada, on the other hand, remains largely mute in the narrative, which is therefore María Sabina’s story. In the text, Estrada’s questions are effaced in favor of María Sabina’s voice and the ongoing narration. He positions himself at the same time in para-texts such as footnotes as a creator-mediator and specialist in the culture, commenting on several vernacular concepts. In effacing himself, the author-witness thus offers a direct narrative. María Sabina thus functioned as an I-witness, like a co-author associated in a half-equal position with the author, who remains a discrete but useful commentor throughout the book.

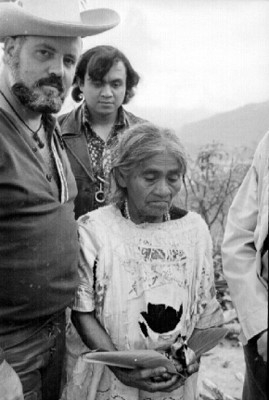

This apparent desire for self-effacement in favor of the subject was extended in 1979 in the film María Sabina, Mujer Espíritu (María Sabina, Spirit Woman), which was directed by the filmmaker Nicolás Echevarría. The “portrait-biography” of the curandera (“healer”), part of a category of films referred to as “cinema-vérité,” “direct cinema,” or “ethnographic cinema”71, shows her engaged in her ordinary activities and her functions as healer. A first-person male voice narrates her life in the background as it was printed in Álvaro Estrada’s book72. As in the written biography, the filmmaker conceals himself to enable the heroine to occupy center-stage, although he orients the frame in order to focus on the celebration. In the end, beyond its objectivism, this film “pursues the invention (in the sense of inventio, discovery) of the individual, by bearing the traces of the social and configuring itself according to her”73.

In this project, Echevarría brought together the few pieces of the puzzle--of voice, image, and text--initially shown by Wasson, although it goes further by articulating them with María Sabina’s everyday life and her sociocultural context. Alongside Álvaro Estrada’s work, Echevarría’s contribution resituates the shaman within the present, and the surrounding poverty. It can therefore be seen as an exercise in counter-exoticization, as opposed to more esoteric and neo-Indian reinterpretations of the shaman. Representations of María Sabina seems to have alternated between these two perspectives--a form of social realism leading back to postcolonial co-temporality and her spiritualization as part of precolonial atemporality. Both realities are expressed in a series of images that evolved more or less directly in tandem with these writings.

Images in Dialogue and Counter-Exoticism

After Allan Richardson’s initial photographs, which focused on María Sabina while she officiated over ceremonies, came other representations, primarily photographic, but also cinematic and pictorial. As was true of writings and narratives surrounding her, the photographs of Wasson’s discovery inspired several later photographers, during a period of receptivity to hybrid images, as discussed by Serge Gruzinski74, whether baroque, muralist, or post-modern. Although their frenetic circulation intersects with recent patterns of consumption, according to Gruzinski, both colonial and contemporary imaginations practice “decontextualization and recycling, as well as both destructuring and restructuring languages”75.

Among Mexican photographers who participated in this growing photographic movement, Nacho Lopez76, who worked for the Instituto Nacional Indigenista (INI) from 1950 to 1981, collaborated periodically with Fernando Benítez and was a friend of Guillermo Bonfil77. As an indigenist photographer, Nacho Lopez resolutely avoided the picturesque78. He was committed to an ethnographic approach that supported development policies, with embellishment, glossing over reality, or forgetting the “authentic drama” of the Indians, who must be presented in their raw social state. Interestingly, Nacho Lopez participated in a 1972 film by a Colombian science-fiction writer, René Rebetez, La Magía, that was inspired by Popol Vuh Maya and was intended to “reveal the occult forces of the universe”79. He was involved in a cine-photographic series devoted to María Sabina that featured other facets of her role as ceremonial leader that complement Allan Richardson’s earlier depictions. In focusing on the ceremony, he followed in the footsteps of Wasson’s initial, much-mediatized distribution centered on María Sabina’s ritual function, relayed by Benítez, who provided a neo-Indian reinterpretation.

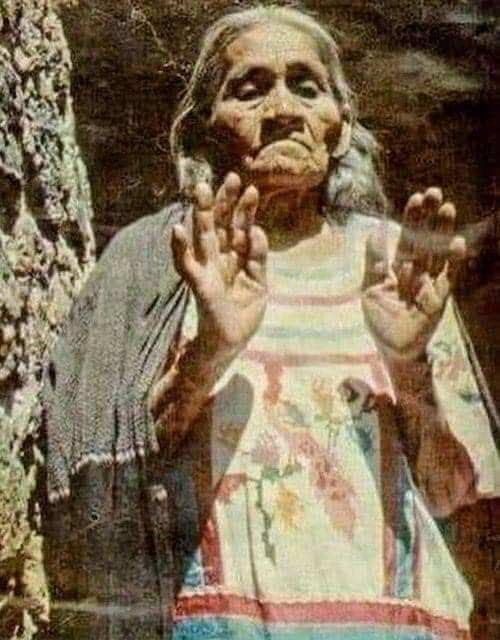

A great deal could be said about the changes that took place in the wake of Richardson’s early photographs, which focused on the shaman immersed in her ritual acts. Their duplication is evidence of the reiteration of the ceremonial experience, as well as the intention of numerous photographers to capture the solemn intimacy of the sacred moments of the first Encounter: Wasson’s mythicized initial discovery. These representations often appear to attempt to capture, albeit in diverse ways, the idea of María Sabina as Paz and Benítez described her, as a “priestess” or “saint.” Because they captured a sacred foundational moment in real time, Richardson’s photos of the ritual, in a play of black-and-white chiaroscuro that accentuated the shadows of faces and bodies, were clearly influential. As Walter Benjamin noted, “opposites touch each other: the most precise technique can give its products a magical value, far more than what we might perceive in a painted image.” According to Benjamin, this quality stems from a photograph’s ability to capture a “spark of chance” or a “here and now” “in the appearance of this long-past minute in which the future still lies”80. The photos of the ritual--some of which have become icons--illustrate the dual paradigm of dissimulation and discovery mentioned earlier: in playing with shadows and darkness, the chiaroscuro reveals as much as it veils amid reflections of the face and moving hands. In this sense, the photographic representation reflected an “optical unconscious”81, that flash of an instant would have vanished in the absence of its photographic source.

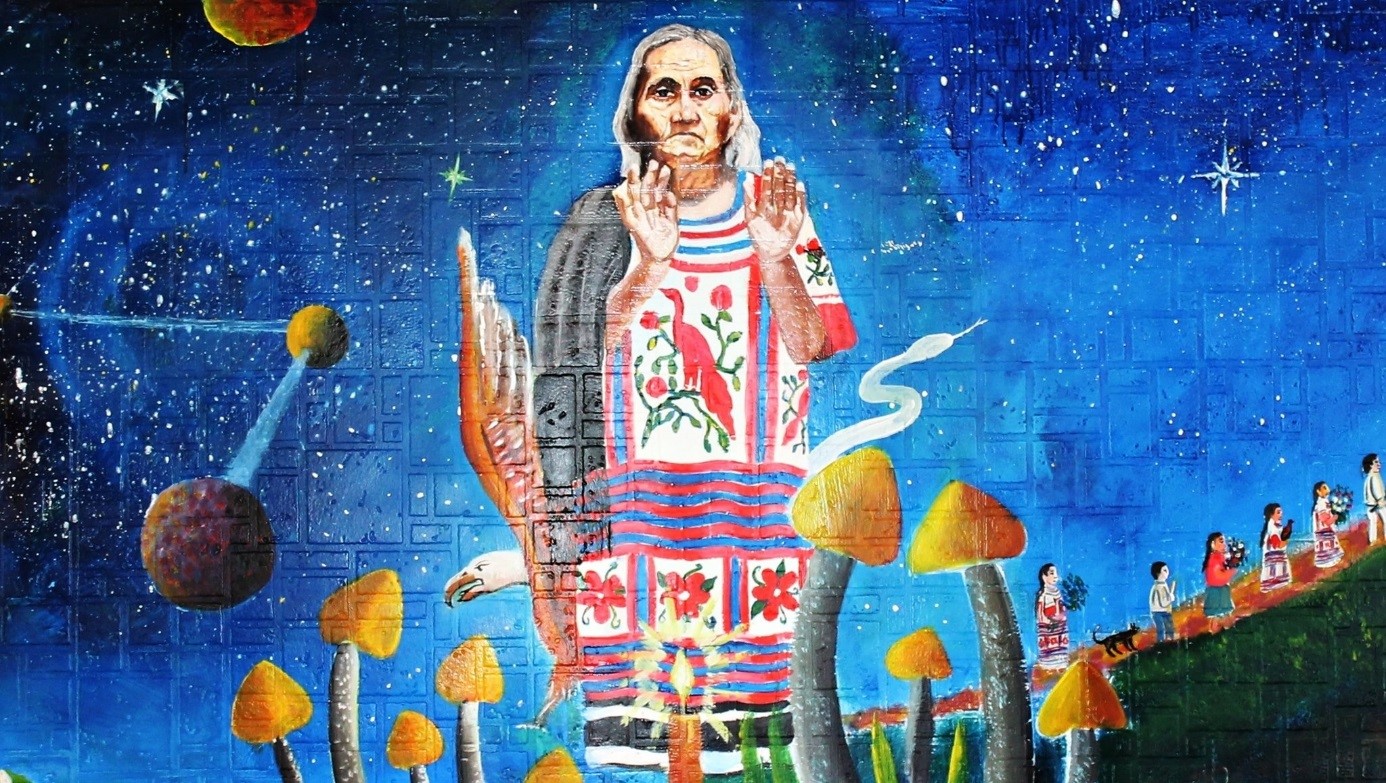

This initial ritual function was to prove central to the María Sabina’s elevation to iconic status. In portraits that followed Richardson’s, María Sabina seems to return to the same original pose, as though her body had been marked by the “optical unconscious” of earlier moments. With raised hands and open palms, she reproduces the posture of invocation that is pictured in mural frescos and a statue at the entrance of her native town, Huautla de Jimenez.

Fig. 2 : María Sabina. Photo provided by Albert Hoffmann to John W. Allen in the 1980s (distributed with his permission).

Other photographs show a ceremonial posture captured by Richardson in which the shaman’s hands are flat across her chest. Here again, the images inspired several painters to represent the shaman as the Virgin of Guadalupe, thus combining the baroque imagination of sacred images with neo-Indianist and nationalist reinterpretations.

Fig. 4 (left) : Allan Richardson, Huautla, 1958

Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann, Les Plantes des Dieux, Paris, Les Éditions du Lézard, 1993, p. 151.

Fig. 5 (right) : Maria Sabina Virgen de Guadalupe.

© J. R. Ruiz (2006), with the permission of José Tlatelpas.

Fig. 6 : Fresco on the wall of the Presidential Residence in Huautla de Jimenez.

These examples illustrate the central role played by photographs in sacralizing María Sabina by shaping her role while also inspiring the gaze of the photographer. They also demonstrate the prevailing discourses surrounding the shaman as incarnating knowledge of an invisible world and its various esoteric psychedelic and religious detours. Among available photos, particularly on the Internet82, very few mention photographers’ names. The photographs are also often unlabeled, increasing the overdetermination of the subject. The image of the icon of Che Guevara seems to grow almost independently of the actual individual who inspired it, taking on its own life: “The image exists as a symbol that transcends the biographical dimension, which has nothing to do with man”83. Partially freed of the identities of their photographers and the lives of their subjects, these images pursue a path that varies according to pictorial reinterpretations, which are in turn inspired and projected onto various media, generating a collective, impersonal creation. This detachment from the original context extends to the baroque representation of the shaman as the Virgin of Guadalupe, the “visual incarnation of the kingdom of New Spain” and a Criollo symbol of a rebaptized Brown Virgin or Virgin of the Indians84. The shaman thus merges with the myth of the saintly image through a process of inversion: the Indianization of the Virgin enables the Indian to become sanctified.

Nacho Lopez appears to have simultaneously taken the opposite perspective by incorporating contradictory aspects of the icon of a sanctified María Sabina. Indeed, Lopez’ indigenist work recently became an official part of national heritage when it entered the archives of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), validating his desire for social and historic contextualization. His series María Sabina consists of a black-and-white photographic narrative based on her life as an Indian peasant life and seen through the prism of the harshness and austerity. We see her atop a hill, her gaze lowered, dressed in a torn huipil85, or appearing frail next to foreign visitors, as though crushed by their height (Photo 7). The photographer shows a particular interest in the healer’s hands in unposed photographs that strangely echo earlier images of the sacralized shaman, while nevertheless inverting their meaning (Photo 8). Her hands lie flat against her body, not in the hieratic posture of a saint, but as if to protect herself. Other images focus closely on her gnarled hands, which are crossed and directed downwards against a background containing a child carrying bundles of sticks (Photo 9). Disconnected from their ritual functions, the hands redirect the viewer’s gaze to a poor Indian woman and her life of toil and misery.

Fig. 7 (left) : Nacho Lopez, « María Sabina en un cerro. Retrato », 1970

Fig. 8 (right) : Nacho Lopez, « María Sabina, retrato », 1980

Fig. 9 : Nacho Lopez, « María Sabina, detalle de sus manos », 1980

Wasson’s “discovery” became part of a powerful tendency to resort to hybrid content and narrative registers. Rather than monological, the dissemination of primitivist ideals and “shamanism” provoked considerable reinterpretations, deflections, and exchanges in Mexico, the United States, and elsewhere. The historical conditions of her reception were determining factors in the elevation of María Sabina to the status of symbol and her association with subaltern meanings and messages. This also raises questions “modern spiritual seekers’” attraction to the primitive, as often portrayed through the lens of an overdetermined Western imagination. At the same time, it suggests that the case of María Sabina is traversed by other imaginary fields that are influenced by both colonial and postcolonial pasts but simultaneously associated with their contemporary iterations.

Indeed, Mexico was convulsed by violent political conflicts in the 1970s, but also by artistic debates that contributed to appropriations and creations that turned towards the past and memory. In light of still-recent memories of state-sponsored violence that was endured mostly in silence, a form of commemoration emerged that focused on a subaltern, neo-Indian interpretation of the national mythology surrounding (pre)colonial history. The figure of María Sabina catalyzes the superimposition of these memorial motifs. On the one hand is her shamanic knowledge, coupled with rituals that included hallucinogenic experiences, which became the basis for the argument of ancient cultural transmission, while on the other is the possibility of an alternative pathway to official History. The ideal of primitivism that was initially projected onto the shaman was also redirected to support counter-cultural, psychedelic notions promoted by the eclectic movement called la onda and a universalist, nationalist viewpoint. In Mexico, this became associated with the desire to reclaim a pre-Hispanic past that had been appropriated by official elites. In the midst of these currents, María Sabina was presented as a figure of resistance and survivor of colonial domination who although physically frail was also indomitable. At the same time, critical reinterpretations centered on the present-day social situation of the Indians also participated in this subterranean historical crossing, thereby inscribing the healer María Sabina within a contemporary socioeconomic context. In other words, this lone figure simultaneously represented the interweaving of ideals of primitivism, the splendors of neo-Indianism, and the social realism of present-day Indians. From this combination, the “illiterate,” victimized Indian, economically excluded from a contemporary society born of colonialism, an image emerged of the Indian who possesses not only alternate ways of knowing, but also of a sublime, ill-understood artistic sensibility.

Analyzing various discursive and iconological strata has helped me become aware of a certain parallelism between the images and narrative developments. Visual representations of the sanctified shaman refocus attention on her message--her ritual chants--understood as the sublime expression of a timeless era and hence a presumably precolonial memory, detaching themselves from the contradictory social background of her difficult life. These narrative itineraries demonstrated that the narration of her life—whether iconographic, filmic, or literary—contributed to the construction of a figure who is a form of oxymoron that links ignorance, poverty, and exclusion to immeasurable wisdom and knowledge. The inversion contained in the symbol renders it memorable and useful for systems of knowledge that are shaped by power relations in a range of postcolonial contexts.

María Sabina is thus simultaneously perceived as a social victim, an emissary of mystery, a poet, and a muse. It is noteworthy that in Mexico, she is brandished in support of Indianist and ethnic demands as a representative of orality, vernacular languages, and Indian literature. Amid this multilingual dialogue—linked to the pact of creation discussed here—she also became the muse of a living form of poetic art. Between Mexico and the United States, she inspires writers who pursue postcolonial studies. Some of these authors are Mexican, including Homero Aridjis86, who develops an environmental critique, and the Mazatec poet and representative of Indian languages, Juan Gregorio Regino. Others are North American, such as Henry Munn and Jérôme Rothenberg87, who represent the field of ethno-poetry inspired by the priestesses’ chants. Still others are African-North Americans, including Alice Walker, an eco-feminist and defender of the Black rights who cited María Sabina in one of her poems88. References to María Sabina are also found in militant postcolonial publications that defend oppressed peoples. An article by the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska89, a militant defender of women’s rights, portrays her as a “shaman” alongside other Mexican “heroines” who have carved themselves places in History as poetesses, painters, or revolutionary fighters. Published in Rencontre, a “Haitian journal of society and culture,” in an issue about the feminine condition, Poniatowska’s article denounced exclusion while promoting enriched cultural pluralism and the cause of the citizens of Haiti and of the world. The symbol of María Sabina has served a range of causes, crossing boundaries and borders. As she has traveled through time and space, she has accumulated symbolic capital as a multi-faceted victim under the yoke of exclusion and domination, principally male because she was a woman, but also capitalist and colonial, because she was also poor, illiterate, and above all, Indian. As a consequence, like the resistance often attributed to other oppressed peoples, her resistance is all the more exemplary.

Notes

1

The term shaman refers to a vernacular term used in Maria Sabina’s territory that is now part of shamanic tourism. In the Mazatec language, these specialists are also referred to as “persons of knowledge” (chjota chjine) and in Spanish as “healers” (curanderos, curanderas).

2

The capital of the Mazatec highlands, the town’s full name is Huautla de Jimenez. It is located in Eastern Oaxaca at an altitude of roughly 1,650 meters and has a population of approximately ten thousand.

3

Benjamin Feinberg, “‘A symbol of wisdom and Love?’ Counter-cultural tourism and the multiple faces of María Sabina in Huautla,” in M. Baud & A. Ypeij (Eds.), Cultural Tourism in Latin America. The Politics of Space and Imagery, Leiden-Boston, Cedla Latin American Studies, vol. 96, 2009, p. 103. On this subject, the author insists on the twinship between the figure of Che and that of Maria Sabina. Although it is true that Che, as a heroic warrior, does not necessarily represent shamanic wisdom, he is nevertheless among the most celebrated images called to represent Mexican and Central American cultures.

4

As seen later, Maria Sabina is defined as resolutely outside modernity. She therefore found herself included in “decolonial” utopias as a primal witness from before the Spanish Conquest. Concerning critical approaches to Spanish colonization and the colonial period, it is important to emphasize the specificity of “postcolonial” positions in the Latin American context. A number of regional writers distinguish themselves from anglophone “post-colonial studies” by basing their argument on the concept of “coloniality.” Linked to a form of modernity that allegedly began with the Conquest of America in the sixteenth century, the concept is more closely associated with the heritage of the Spanish and Portuguese empires. Studies by Latin American authors thus differ from postcolonial studies in displaying a more critical, offensive posture in their “decolonial” theories centered on long-term rootedness in coloniality and its contemporary economic, racial, and social implications. See Capucine Boidin, “Études décoloniales et postcoloniales dans les débats français,” Cahiers des Amériques latines, n° 62, 2009, p. 129-140; Claude Bourguignon & Philippe Colin, “De l’universel au pluriversel. Enjeux et défis du paradigme décolonial,” Raison présente, vol. 199, n° 3, 2016, p. 99-108.

5

Jean-Claude Chamboredon, “Production symbolique et formes sociales. De la sociologie de l’art et de la littérature à la sociologie de la culture,” Revue française de sociologie, vol. 27, n° 3, 1986, p. 526. The author is notably inspired by Erwin Panofsky to propose a sociology of symbolic productions by analyzing how they are articulated with their functions in terms of socialization.

6

Jean-Claude Chamboredon, “Production symbolique et formes sociales. De la sociologie de l’art et de la littérature à la sociologie de la culture,” Revue française de sociologie, vol. 27, n° 3, 1986, p. 526.

7

I draw on studies by Ben Etherington, Literary Primitivism, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2018. I am especially inspired by comments made about his book by Jehanne Denogent and Nadejda Magnenat in “Décoloniser le primitivisme,” Acta fabula, vol. 21, n° 2, Essais critiques, 2020. From this point of view, “reterritorializing” the notion of primitivism suggests considering it not through its construction by Western authors, but by examining the historical context that inspired it and the dialogue with authors from the country.

8

According to terms used by Michel Foucault, Histoire de la sexualité, I, La volonté de savoir, Paris, Gallimard, 1994 [1976].

9

Álvaro Estrada (data collected by), Autobiographie de Maria Sabina. La Sage aux Champignon Sacrés, Paris, Le Seuil, 1979.

10

It has been endlessly repeated on the Internet and shared far beyond Mexico by those from the 1970s generation or who are inspired by that period.

11

Gordon R. Wasson, “Seeking the magic mushroom,” Life, vol. 49, n° 19, 13 May 1957, p. 100-120.

12

Gordon R. Wasson, “Chapitre II- Le champignon sacré in Mexico Contemporain,” in G. R. Wasson & R. Heim (Eds.), Les Champignons hallucinogènes du Mexique. Études ethnologiques, taxinomiques, biologiques, physiologiques et chimiques, Archives du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 7e série, 1958, p. 50.

13

Presented in articles reporting Wasson’s discovery, this is clearly the result of the cultural organization of the New York Historical Society, which operates one of the oldest, eponymous museums in New York.

14

Gordon R. Wasson, Mushroom Ceremony of the Mazatec Indians of Mexico, New York, Folkways Records and Service Corp., 1957.

15

See Magali Demanget, “La patrimonialisation de l’occulte. Secret et écritures en terres mazatèques (Mexico),” Mondes contemporains, n° 5, 2014, p. 29-52.

16

See, for example, Andrei A. Znamenski, The Beauty of the Primitive. Shamanism and the Western Imagination, New York, Oxford University Press, 2007. The author retraces the ways in which stories were written about “modern spiritual seekers” and returns to the beauty of the primitive in the Western imagination that gravitates around shamanism.

17

There are literary antecedents in the form of travel narratives with romanticized testimony. See, in particular, Magali Demanget, “Quand le secret devient parure. Les passeurs de chamanisme chez les Indiens mazatèques (Mexico),” in G. Ciarcia (Ed.), Ethnologues et passeurs de mémoires, Paris, Karthala-MSH-M, 2011, p. 173-174.

18

Dominique Rabaté, “Le secret et la modernité,” Modernités, n° 14, 2001, p. 9-32. See also Michel Foucault, Histoire de la sexualité, I, La volonté de savoir, Paris, Gallimard, 1994 [1976].

19

See Gordon R. Wasson, “El Hongo Sagrado en el México Contemporáneo,” Espacios, t. XIV, n° 20, 1996 [1957]. Fernando Benitez (1964 [1969], p.18-34), cited earlier, also summarizes the phases of the discovery of his Mexican publications. See also Magali Demanget, “La patrimonialisation de l’occulte. Secret et écritures en terres mazatèques (Mexique),” Mondes contemporains, n° 5, 2014, p. 29-52.

20

Nicholas Thomas & Caroline Humphrey, “Introduction,” in Nicholas Thomas & Caroline Humphrey (Eds.), Shamanism, History and the State, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1996, p. 2.

21

Beginning in October 1957, The Mexican-Italian writer Gutierre Tibón communicated Watson’s “discovery” of mushrooms in the editorial pages of the newspaper Excélsior (José Augustín, La Contracultura en México. La historia y el significado de los rebeldes sin causa, los jipitecas, los punks y las bandas, Mexico City, Grijalbo, 1996, p. 53). In 1964, Fernando Benitez published Los Hongos Alucinantes, a book in which he retold and embellished Gordon R. Wasson’s primitivist rhetoric.

22

Fernando Benitez, Los Hongos Alucinantes, Mexico, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964], p. 79. The book, which consists of three parts, devotes the second and third sections to Maria Sabina and the author’s hallucinogenic experience.

23

Wasson, who had no academic training or institutional affiliation, also developed his scientific legitimacy through interdisciplinary collaborative research. This included linguists from the ILV, Eunice Victoria Pike and George and Florence Cowan, as well as Roger Heim, a biologist with the Museum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris and the eminent Mexicanist anthropologists Roberto Weitlaner and Guy Stresser Pan, who accompanied him on his expeditions.

24

Indeed, it was only after he retired that he discussed his travels with Wasson (he was born in 1913) in a book published in 1990 and reprinted seven years later. The book reunited the key participants in the discovery of Maria Sabina and the sacred mushrooms. See Guy Stresser-Péan, “Travels with R. Gordon Wasson in Mexico, 1956-1962,” in Thomas J. Riedlinger (Ed.), The Sacred Mushroom Seeker. Essays for R. Gordon Wasson, Rochester, Park Street Press, 1997 [1990], p. 231-238. This was also true of another renowned Mexican anthropologist, Roberto Weitlaner, who participated in the expeditions but whose name was systematically misspelled in public documents. In the article in Life, for example, the misspelling “Waitlaner” was used in the English-language edition, while the equally erroneous spelling “Weitlander” appeared in the Spanish edition. The latter error was repeated in the previously cited book by Fernando, Los Hongos Alucinantes (Mexico City, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964]), which was published eight years later.

25

Claude Lévi-Strauss “Les champignons dans la culture. À propos d’un livre de R. G. Wasson,” in Anthropologie Structurale, Paris, Plon, 1996 [1973].

26

Carlos Inchaustegui, “Cinco años y un programa. El centro coordinador indigenista de la Sierra Mazateca,” América Indígena, vol. 26, n° 1, 1966.

27

This includes every generation through the 1990s.

28

Andrés Medina, “¿Etnología o literatura? El caso de Benítez y sus indios,” Anales de antropología, n° 11, 1974.

29

Andrés Medina, “¿Etnología o literatura? El caso de Benítez y sus indios,” Anales de antropología, n° 11, 1974, p. 121.

30

Andrés Medina, “¿Etnología o literatura? El caso de Benítez y sus indios,” Anales de antropología, n° 11, 1974, p. 123.

31

Andrés Medina, “¿Etnología o literatura? El caso de Benítez y sus indios,” Anales de antropología, n° 11, 1974, p. 121.

32

Fernando Benitez, Los Hongos Alucinantes, Mexico, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964], p. 44-52.

33

In principle founded on universal equality, the national plan clashed with the issue of colonized minorities. Successively excluded after independence, minorities were seen as a “problem” to solve due to increased racial mixing after the 1910 Revolution, before being seen as a positive resource in support of policies recognizing neoliberal multiculturalism. For a synthesis, see Pierre Beaucage, “Un débat à plusieurs voix: les Amérindiens et la nation in Mexico,” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, vol. 25, n° 4, 1995, p. 15-30.

34

Claudio Lomnitz, Modernidad Indiana. Nueve ensayos sobre nación y mediación en México, Mexico City, Planeta (coll. “Espejo Mexicano”), 1999, p. 62.

35

Kimberle Lopez, cited by Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero, “El testimonio problematizado en Hasta no verte Jesús mío: convergencias y divergencias con Oscar Lewis en la reconstrucción del Otro,” in Carla Fernandes (Ed.), D’oublis et d’Abandons. Notes sur l’Amérique latine, Binjes, Orbis Tertius, 2017, p. 69. Regarding the idea of internal colonialism, it should be noted that it was initially developed by Mexican sociologists in the 1960s who cited a continuum between the colonial and post-colonial periods, postulating that relations of economic and political domination persisted long after independence. It is also interesting to note that this notion is part of decolonial theories referred to earlier, and that this identification is articulated with the goals of development that decolonization made possible. See, in particular, Pablo González Casanova, “Société plurale, colonialisme interne et développement,” Tiers-Monde, t. 5, n° 18, 1964, p. 291-295.

36

Eliot Weinberger, “Elogio de la droga,” Semanal, n° 169, 6 September 1992, p. 20. Note that this North American writer had translated the work of Octavio Paz in the 1960s. He later became committed to ethno-poetry.

37

In Maria Sabina’s home territory, the State of Oaxaca, this emergence dates from the 1970s (Guillermo de la Peña, “Territoire et citoyenneté ethnique dans la nation globalisée,” in Marie-France Prévot Scharpia et Hélène Rivière d’Arc (Eds.), Les Territoires de l’État-nation en Amérique Latine, Paris, IHEAL, 2001; Raúl Víctor Martínez Vásquez, Movimiento Popular y Política en Oaxaca: 1968-1986, Mexico City, CNCA, 1990).

38

Margarita Nolascos Armas, “La antropología aplicada en México y su destino final,” in Mercedes Olivera et al. (Eds.), De eso que llaman antropología mexicana, Mexico City, Comité de publicaciones de Los alumnos de la ENAH, 1970, p. 66.

39

See Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, Lo indio desindianisado, in México Profundo. Una civilización negada, Mexico City, Grijalbo, 1994 [1987], p. 73-96.

40

Annick Lempérière-Roussin, “Le mouvement de 1968 in Mexico,” Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, n° 23, 1989, p. 78.

41

“La Cultura en México,” Siempre!, n° 349, 23 October 1968.

42

Fernando Benitez, “Los días de la ignominia,” Siempre!, n° 349, 23 October 1968.

43

See also Elena Poniatowska, La noche de Tlatelolco: Testimonios de historia oral, who published on this subject in 1971. Other authors, including the poet Octavio Paz, established the parallel between massacre and sacrifice in pre-Colombian civilizations. The book by Regina de Velasco Piña, 1987, returned to the subject of the Tlatelolco massacre in a fiction in which the author laid the foundations of a neo-Indian Mexican cult, the Reginistas (a cult discussed in Jacques Galinier & Antoinette Molinié, Les Néo-Indiens. Une religion du IIIe millénaire, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2006). With regard to María Sabina, she appears in numerous literary (see writings by authors identified with La Onda such as Enrique Maroquin and Jorge Augustin) and musical (Mexican rock, the group El TRI, see “María Sabina es un símbolo”) neo-Indian and psychedelic reinterpretations.

44

Jean-Claude Chamboredon, “Production symbolique et formes sociales. De la sociologie de l’art et de la littérature à la sociologie de la culture,” Revue française de sociologie, vol. 27, n° 3, 1986, p. 515-519.

45

Andrés Medina Hernández, “¿Etnología o literatura? El caso de Benítez y sus indios,” Anales de antropología, n° 11, 1974, p. 136.

46

Jean-Claude Chamboredon, “Production symbolique et formes sociales. De la sociologie de l’art et de la littérature à la sociologie de la culture,” Revue française de sociologie, vol. 27, n° 3, 1986, p. 519.

47

Lucero Margarita Aguirre-Valdés, “Los huicholes, de Fernando Benítez: un relato de viaje,” La colmena, n° 87, 2015, p. 25-37.

48

Raphaële Plu-Jenvrin, “Mémoire, chronique et discours culturel dans le Mexico de l’après 1968,” Mémoire et culture en Amérique latine, América. Cahiers du CRICCAL, n° 30, 2003, p. 117-124.

49

Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero, “El etnógrafo: autor, mediador y empatía en La noche de Tlatelolco, Chin Chin el teporocho y Vida de María Sabina,” Literatura Mexicana, vol. XXIX, n° 1, 2018, p. 107.

50

As James Clifford described it, “post-anthropological” or “post-literary” (James Clifford, “Introduction: Partial Truths,” in James Clifford & George E. Marcus (Eds.), Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986, p. 5).

51

Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero, “El etnógrafo: autor, mediador y empatía en La noche de Tlatelolco, Chin Chin el teporocho y Vida de María Sabina,” Literatura Mexicana, vol. XXIX, n° 1, 2018, p. 108. As she noted, E. P. Poniatowska initiated new registers that highlighted a range of subjectivities and that were precursors to the ethnographic writing as recommended ten years later by James Clifford.

52

Cited in Álvaro Estrada, Autobiographie de Maria Sabina, La Sage aux Champignon Sacrés, Paris, Le Seuil, 1979, p. 109.

53

Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, México Profundo. Una civilización negada, Mexico City, Grijalbo, 1994 [1987].

54

Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, México Profundo. Una civilización negada, Mexico City, Grijalbo, 1994 [1987], p. 10.

55

See Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero, “El etnógrafo: autor, mediador y empatía en La noche de Tlatelolco, Chin Chin el teporocho y Vida de María Sabina,” Literatura Mexicana, vol. XXIX, n° 1, 2018, p. 99-124.

56

See in particular his description of the ceremony in which he participated with the anthropologist Carlos Inchaustegui (among others) (Fernando Benitez, Los Hongos Alucinantes, Mexico City, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964], in particular, Part 3: “Delirios y extasis,” p. 83-126).

57

Magali Demanget, “Aux sources d’une communauté imaginée. Le tourisme chamanique à Huautla de Jimenez (Indiens mazatèques, Mexique),” Ethnologies, vol. 32, n° 2, 2010, p. 218.

58

Fernando Benitez, “La santa de los hongos, vida y misterio de Marla Sabina,” RUMex, XVIII, 1 September 1963, p. 15.

59

Miriam Hernández Reyna, “Memoria histórica y pluralidad cultural en México: un nuevo imaginario sobre el pasado ‘indígena’ para un futuro posible,” Revista Cambios y Permanencias, vol. 8, n° 2, 2017, p. 736-768.

60

Miriam Hernández Reyna, “Memoria histórica y pluralidad cultural en México: un nuevo imaginario sobre el pasado ‘indígena’ para un futuro posible,” Revista Cambios y Permanencias, vol. 8, n° 2, 2017, p. 744.

61

The “Ciclo de Chiapas” was identified by Joseph Sommers, “El ciclo de Chiapas: nueva corriente literaria,” Cuadernos Americanos, March-April 1964, p. 246-261. It discusses critical indigenist literature from the 1930s to the 1960s, consisting of books about Indian ethnic groups in the State of Chiapas.

62

Fernando Benitez, Los Hongos Alucinantes, Mexico City, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964], p. 45-56.

63

Fernando Benitez, Los Hongos Alucinantes, Mexico City, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964], p. 44.

64

The literal translation of the book’s Spanish-language title. Significant care was paid to the life narrative in the original edition.

65

Translated from Spanish into English, French, German, and Italian.

66

James Clifford, “Introduction: Partial Truths,” in James Clifford & George E. Marcus (Eds.), Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986, p. 8-9.

67

Álvaro Estrada, “Introduction to the Life of María Sabina,” in Jerome Rothenberg (Ed.), María Sabina. Selections, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2003, p. 130-131.

68

These studies, instigated by Wasson, involved collaboration with ILV linguists. álvaro Estrada was later asked to explain and complete still-unresolved translation issues that remained (álvaro Estrada, “Introduction to the Life of María Sabina,” in Jerome Rothenberg (Ed.), María Sabina. Selections, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2003, p. 130-131).

69

Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero, “El etnógrafo: autor, mediador y empatía en La noche de Tlatelolco, Chin Chin el teporocho y Vida de María Sabina,” Literatura Mexicana, vol. XXIX, n° 1, 2018, p. 122.

70

Ana Lourdes Álvarez Romero, “El etnógrafo: autor, mediador y empatía en La noche de Tlatelolco, Chin Chin el teporocho y Vida de María Sabina,” Literatura Mexicana, vol. XXIX, n° 1, 2018, p. 122.

71

Concerning the history of these different terminologies and their theoretical implications, see Séverine Graff, “‘Cinéma-vérité’ ou ‘cinéma direct’: hasard terminologique ou paradigme théorique?,” Décadrages, n° 18, 2011, p. 32-46.

72

As Echevarria explains, using a masculine voice was deliberate decision. It was not a matter of imitation or presenting it as Maria Sabina’s voice, but on the contrary of preserving the documentary realism of the film.

73

Dario Marchiori, “Le cinéma direct: du sujet retrouvé à l’invention du subjectif,” Cahier Louis-Lumière, n° 8, 2011, p. 43.

74

Serge Gruzinski, La Guerre des images. De Christophe Collomb à “Blade Runner”, Paris, Fayard, 1990.

75

Serge Gruzinski, La Guerre des images. De Christophe Collomb à “Blade Runner”, Paris, Fayard, 1990, p. 335.

76

Ignacio López Bocanegra (1923-1986).

77

See Óscar Colorado Nates, “Nacho López, entre lo documenta y lo autoral,” Archivo de la etiqueta: Guillermo Bonfil, Oscar en Fotos, 7 December 2012. While also representing the photographer’s itinerary, the article offers an overview of his work.

78

Óscar Colorado Nates, “Nacho López, entre lo documenta y lo autoral,” Archivo de la etiqueta: Guillermo Bonfil, Oscar en Fotos, 7 December 2012.

79

From the advertising poster of the film (René Rebetez, La Magía, Mexico, 1972).

80

Walter Benjamin, “Petite histoire de la photographie,” Études photographiques, n° 1, 1996, p. 3.

81

Walter Benjamin, “Petite histoire de la photographie,” Études photographiques, n° 1, 1996, p. 3.

82

In addition to her presence on Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram, it is worth citing the following French-language web pages: [Maria Sabina (oniros.fr)]; [Maria Sabina: La femme champignon magique (mind-gravy.com)]; [Doc // Qui était la chamane Maria Sabina? | Thérapie Anankea (therapie-anankea.com)].

83

Frédéric Maguet, “Le portrait de Che Guevara,” Gradhiva, n° 11, 2010, p. 144.

84

I have merely sketched this interplay of transpositions, which merit further development. The abundant literature on this national icon is beyond the scope of this article, but for more information, see the chapter by Ana Cecilia Hornedo Marin, “L’invocation à la Vierge de Guadalupe et les paradoxes de la Révolution mexicaine,” in Anne Creissels & Giovanna Zapperi (Eds.), Subjectivités, pouvoir, image. L’histoire de l’art travaillée par les rapports coloniaux et les différences sexuelles, Toulouse, EuroPhilosophie édition, 2017. The author examines the metamorphoses of the Virgin in the wake of the Mexican Revolution, particularly the inversions involved in post-revolutionary representations. See also Jacques Lafaye’s classic book, Quetzalcóatl et Guadalupe. La formation de la conscience nationale in Mexico (1531-1813), Paris, Gallimard, 1974. The author cites the origins of the creation myth of the Creolized, Mexicanized Virgin and her relationship with the Aztec goddess Tonantzin to explain her conversion into a “patriotic epiphany” on Independence.

85

Huipil [a Nahuatl word]: a traditional Indian article of clothing.

86

Homero Aridjis, Carne de Dios, Mexico City, Alfaguara, 2003.

87

See in particular Jerome Rothenberg (Ed.), with texts and commentaries of Álvaro Estrada and others, Maria Sabina. Selections, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2003. The book includes articles by North American authors, including, posthumously, Wasson, and Mexican, including two Mazatec authors, álvaro Estrada, and the poet Juan Gregorio Regino).

88

Bring Me the Heart of Maria Sabina. Alice Walker, Absolute Trust in the Goodness of the Earth. New Poems, New York, Random House, 2003.

89

Elena Poniatowska, “Femmes, peintures et politique du Mexico,” Rencontre. Revue haïtienne de société et de culture, n° 28-29, 2013, p. 149-155.

Bibliographie

Aguirre Valdés Lucero Margarita, « Los huicholes, de Fernando Benítez: un relato de viaje », La colmena, n° 87, 2015, p. 25-37.

Álvarez Romero Ana Lourdes, « El etnógrafo: autor, mediador y empatía en La noche de Tlatelolco, Chin Chin el teporocho y Vida de María Sabina », Literatura Mexicana, vol. XXIX, n° 1, 2018, p. 99-124.

—, « El testimonio problematizado en Hasta no verte Jesús mío: convergencias y divergencias con Oscar Lewis en la reconstrucción del Otro », in Carla Fernandes (dir.), D’oublis et d’Abandons. Notes sur l’Amérique latine, Binjes, Orbis Tertius, 2017, p. 59-74.

Aridjis Homero, Carne de Dios, Mexico, Alfaguara, 2003.

Augustín José, La Contracultura en México. La historia y el significado de los rebeldes sin causa, los jipitecas, los punks y las bandas, Mexico, Grijalbo, 1996.

Beaucage Pierre, « Un débat à plusieurs voix : les Amérindiens et la nation au Mexique », Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, vol. 25, n° 4, 1995, p. 15-30.

Benítez Fernando, Los Hongos Alucinantes, México, Serie Popular Era, 1969 [1964].

—, « Los días de la ignominia », Siempre!, n° 349, 23 octobre 1968.

—, « La santa de los hongos, vida y misterio de Marla Sabina », RUMex, vol. XVIII, 1er septembre 1963, p. 15-20.

Benjamin Walter, « Petite histoire de la photographie », Études photographiques, no 1, 1996 [en ligne].

Boidin Capucine, « Études décoloniales et postcoloniales dans les débats français », Cahiers des Amériques latines, n° 62, 2009, p. 129-140.

Bonfil Batalla Guillermo, México Profundo. Una civilización negada, Mexico, Grijalbo, 1994 [1987].

Bourguignon Claude et Colin Philippe, « De l’universel au pluriversel. Enjeux et défis du paradigme décolonial », Raison présente, vol. 199, n° 3, 2016, p. 99-108.

Chamboredon Jean-Claude, « Production symbolique et formes sociales. De la sociologie de l’art et de la littérature à la sociologie de la culture », Revue française de sociologie, vol. 27, n° 3, 1986, p. 505-529.

Clifford James, « Introduction : Partial Truths », in James Clifford, George E. Marcus (dir.), Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986, p. 1-50.

Collectif, « La Cultura en México », Siempre!, n° 349, 23 octobre 1968.

Colorado Nates Óscar, « Nacho López, entre lo documenta y lo autoral », Archivo de la etiqueta: Guillermo Bonfil, Oscar en Fotos, 7 Diciembre, 2012 [en ligne].

Demanget Magali, « La patrimonialisation de l’occulte. Secret et écritures en terres mazatèques (Mexique) », Mondes contemporains, n° 5, 2014, p. 29-52.

—, « Quand le secret devient parure. Les passeurs de chamanisme chez les Indiens mazatèques (Mexique) », in Gaetano Ciarcia (dir.), Ethnologues et passeurs de mémoires, Paris, Karthala-MSH-Montpellier, 2011, p. 171-194.

—, « Aux sources d’une communauté imaginée. Le tourisme chamanique à Huautla de Jimenez (Indiens mazatèques, Mexique) », Ethnologies, vol. 32, n° 2, 2010, p. 199-232.

Denogent Jehanne et Magnenat Nadejda, « Décoloniser le primitivisme », Acta fabula, vol. 21, n° 2, 2020 [en ligne].

Estrada Álvaro, « Introduction to the Life of María Sabina », in Jerome Rothenberg (dir.), María Sabina. Selections, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2003, p. 127-132.

—, (propos recueillis par) Autobiographie de Maria Sabina, La Sage aux Champignon Sacrés, Paris, Le Seuil, 1979.

—, Vida de María Sabina, la Sabia de los Hongos, México, Siglo XXI, 1977.

Etherington Ben, Literary Primitivism, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2018.

Feinberg Benjamin, « “A symbol of wisdom and Love?” Counter-cultural tourism and the multiple faces of María Sabina in Huautla », in Michiel Baud, Annelou Ypeij (dir.), Cultural Tourism in Latin America. The Politics of Space and Imagery, Leiden-Boston, Cedla Latin American Studies, vol. 96, 2009, p. 93-114.

Foucault Michel, Histoire de la sexualité, I, La volonté de savoir, Paris, Gallimard, 1994 [1976].

Galinier Jacques et Molinié Antoinette, Les Néo-Indiens. Une religion du IIIe millénaire, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2006.

González Casanova Pablo, « Société plurale, colonialisme interne et développement », Tiers-Monde, t. 5, n° 18, 1964, p. 291-295.

Graff Séverine, « “Cinéma-vérité” ou “cinéma direct” : hasard terminologique ou paradigme théorique ? », Décadrages, n° 18, 2011, p. 32-46.

Gregorio Regino Juan, « Escritores en lenguas indígenas », in Carlos Montemayor (dir.), Situación actual y perspectivas de la Literatura en Lenguas Indígenas, Mexico, Consejo Nacional para las Culturas y las Artes, 1993, p. 119-137.

Gruzinski Serge, La Guerre des images. De Christophe Collomb à « Blade Runner », Paris, Fayard, 1990.

Hernández Reyna Miriam, « Memoria histórica y pluralidad cultural en México: un nuevo imaginario sobre el pasado “indígena” para un futuro posible », Revista Cambios y Permanencias, vol. 8, n° 2, 2017, p. 736-768.

Hornedo Marin Ana Cecilia, « L’invocation à la Vierge de Guadalupe et les paradoxes de la Révolution mexicaine », in Anne Creissels, Giovanna Zapperi (dir.), Subjectivités, pouvoir, image. L’histoire de l’art travaillée par les rapports coloniaux et les différences sexuelles, Toulouse, EuroPhilosophie édition, 2017 [en ligne].

Inchaustegui Carlos, « Cinco años y un programa. El centro coordinador indigenista de la Sierra Mazateca », América Indígena, vol. 26, n° 1, 1966, p. 12-26.

Lempérière-Roussin Annick, « Le mouvement de 1968 au Mexique », Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, n° 23, 1989, p. 71-82.

Lévi-Strauss Claude, « Les Champignons dans la culture. À propos d’un livre de R. G. Wasson », in Anthropologie Structurale, Paris, Plon, 1996 [1973], p. 263-279.

Lomnitz Claudio, Modernidad Indiana. Nueve ensayos sobre nación y mediación en México, Mexico, Planeta, 1999.

Maguet Frédéric, « Le portrait de Che Guevara », Gradhiva, no 11, 2010, p. 141-159.

Martinez Vásquez Raúl Víctor, Movimiento Popular y Política en Oaxaca: 1968-1986, Mexico, CNCA, 1990.

Marchiori Dario, « Le cinéma direct : du sujet retrouvé à l’invention du subjectif », Cahier Louis-Lumière, n° 8, 2011, p. 40-49.

Medina Hernández Andrés, « ¿Etnología o literatura? El caso de Benítez y sus indios », Anales de antropología, n° 11, 1974, p. 109-140.

Nolascos Armas Margarita, « La antropología aplicada en México y su destino final », in Mercedes Olivera et al. (dir.), De eso que llaman antropología mexicana, México, Comité de publicaciones de Los alumnos de la ENAH, 1970, p. 66-93.

Peña Guillermo de la, « Territoire et citoyenneté ethnique dans la nation globalisée », in Marie-France Prévot Scharpia, Hélène Rivière d’Arc (dir.), Les Territoires de l’État-nation en Amérique Latine, Paris, IHEAL, 2001, p. 282-300.

Plu-Jenvrin Raphaële, « Mémoire, chronique et discours culturel dans le Mexique de l’après 1968 », Mémoire et culture en Amérique latine, América, Cahiers du CRICCAL, n° 30, 2003, p. 117-124.

Poniatowska Elena, La noche de Tlatelolco, México, Ediciones Era, 2015 [1970].

—, « Femmes, peintures et politique du Mexique », Rencontre. Revue haïtienne de société et de culture, n° 28-29, 2013, p. 149-155.

Rabaté Dominique, « Le secret et la modernité », Modernités, n° 14, 2001, p. 9-32.

Rothenberg Jerome (dir), Maria Sabina. Selections, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2003.

Ruffinelli Georges, « María Sabina Mujer Espíritu », in América Latina en 130 documentales, Chili, Uqbar editores, 2012, p. 68-69.

Sommers Joseph, « El ciclo de Chiapas: nueva corriente literaria », Cuadernos Americanos, marzo-abril 1964, p. 246-261.

Stresser-Péan Guy, « Travels with R. Gordon Wasson in Mexico, 1956-1962 », in Thomas J. Riedlinger (dir.), The Sacred Mushroom Seeker. Essays for R. Gordon Wasson, Rochester, Park Street Press, 1997 [1990], p. 231-238.

Thomas Nicholas et Humphrey Caroline, « Introduction », in Nicholas Thomas et Caroline Humphrey (dir.), Shamanism, History and the State, University of Michigan Press, 1996, p. 1-12.

Walker Alice, Absolute Trust in the Goodness of the Earth. New Poems, New York, Random House, 2003.

Wasson Gordon R., « Chapitre II- Le champignon sacré au Mexique Contemporain », in G. R. Wasson, R. Heim (dir.), Les Champignons Hallucinogènes du Mexique. Études ethnologiques, taxinomiques, biologiques, physiologiques et chimiques, Archives du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, 7e série, 1958, p. 45-100.

—, « Seeking the magic mushroom », Life, vol. 49, n° 19, 13 may 1957, p. 100-120.

—, Mushroom Ceremony of the Mazatec Indians of Mexico, New York, Folkways Records and Service Corp, 1957.

Wasson Gordon R. et Heim Roger (dir.), Les Champignons Hallucinogènes du Mexique. Études ethnologiques, taxinomiques, biologiques, physiologiques et chimiques, Archives du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Septième série, Paris, 1958.

Weinberger Eliot, « Elogio de la droga », Semanal, n° 169, 6 septembre 1992, p. 17-20.

Znamenski Andrei A., The Beauty of the Primitive. Shamanism and the Western Imagination, New York, Oxford University Press, 2007.