Taiwan: a history of the island’s colonisation

In an effort to keep pace with Korea, the Government-General of Taiwan launched a programme designed to institutionalise the human and social sciences in the early 1920s.

This included the creation in 1922 of the Taiwan Government-General Committee for the Compilation of Historical Materials (Taiwan sōtokufu shiryō hensan iinkai 臺灣總督府史料編纂委員會)1 and the establishment of Taihoku (Taipei) Imperial University in 1928.

Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan

The Committee for the Compilation of Historical Materials (henceforth the Committee) was founded by the governor-general Den Kenjirō 田健治郎 (1855–1930, in office from 1919 to 1923)

by decree no. 101 on 1 April 19222.

Mochiji Rokusaburō (mentioned in Part I) was appointed chair of the Committee and its related bodies3.

His duties included supervising the Committee’s research and compilation work, which was carried out by a smaller team than its Korean counterpart.

Notable members included Tahara Teijirō 田原禎次郎 (1868–1923), classical Chinese expert Ozaki Hotsuma 尾崎秀眞 (1874–1952)4, Inō Kanori, who was back in Taiwan specifically for the Committee, linguist Ogawa Isayoshi 小川尚義 (1869–1947), who had trained at Tōkyō Imperial University under Ueda Kazutoshi 上田萬年 (1867–1937)5, and Taiwanese supporters of the Japanese6.

The initial objective was to produce a History of New Taiwan (Shin Taiwan shi 新臺灣史) that would serve as a counter-discourse to works published in continental China and elsewhere – the Taiwanese figure Lien Hweng 連橫 (1878–1936) and his Complete History of Taiwan7, published in 1921, echoes the Korean Pak Ŭnsik – by emphasising the specificity of Taiwan in relation to Asia and the island’s proximity to Japan. Lien’s work, which presented the unbroken history of Taiwan from the Sui Dynasty (605) to 1895, illustrates how the continuist view of history had become widespread. The title of the book planned by the Committee can also be translated as New History of Taiwan, but History of New Taiwan seems a more accurate translation due to the work’s emphasis on the period after 1895, as we shall see.

Mochiji set out the Committee’s objectives at a lecture in July 1922. The text was published in Japanese and Chinese the following month in the journal Taiwan jihō 臺灣時報.

The setting up of this committee was driven by our observation that the historical records of our rule in Taiwan since we took possession of the island 27 years ago, more than a quarter of a century ago now, have never been accurately compiled. If they were abandoned, the archives [relating to colonial rule] risk being lost as staff working for the government-general leave or die. The value of these documents must be recognised so that they may be presented to society and prevented from being lost. It is therefore urgent that we compile a complete history of the government-general. We plan to carry out and complete this work over three years, from Taishō 11 to Taishō 13 [1922 to 1924]. The motivations, content and general orientation of this historical project will be limited to those set out below8.

Liquor trademarks of the Taiwan Government-General Monopoly Bureau in 1929 and 1937

He went on to underline – like the Japanese historians of Korea – that Japan needed to revolutionise the paradigm applied to the writing of Taiwan’s history by rejecting earlier Manchu bureaucratic works.

Until now, “Chinese-style” works on the history of the prefectural government focused on its actions, failures and successes, not on politics and the economy, or the joys and hardships of the population. These bureaucratic publications cannot be considered pertinent due to the approach they adopted, which spurned contemporary methodology in history writing and in Western-style writing about the history of civilisation. The Committee’s work will thus seek to achieve a balance between Chinese-style prefectural histories and the form adopted by Western historical works, all the while respecting the objectives and contents defined for this project…. Historical facts are always linked to a wider context and are thus interconnected: isolated historical facts do not exist. For this reason, anyone wanting to write the history of the governance of Taiwan must be equally versed in the intentions of the government and popular sentiment, as well as in the political situation and popular sentiment within the Japanese Empire during the same period. Furthermore, these elements must be placed in the global context, highlighting the Japanese Empire’s place in the global dynamics of the period in question9.

This ambitious project was divided into five parts. Part one was to provide an overview of the island’s history and geography, as well as relations between Japan and Taiwan. However, the subsequent sections all focused on Japan’s conquest of the island and the history of Japanese rule since 1895. Extensive bibliographies (Tosho sōmokuroku 圖書總目錄 and Tosho kaidai 圖書解題) were also planned, just as in Korea. And yet, this initial History of New Taiwan never saw the light of day. Several factors caused the project to fail. One was the fact that supervision of the project was entrusted jointly to Tahara, Ozaki and Mochiji, the latter of whom had lived mostly in Tōkyō since the end of his term of office at the Government-General of Korea in 192110. The project was further hampered by the deaths of Mochiji and Tahara in 1923.

The outcome of this initial failure – as in Korea after the failure of the 1911 Hantō-shi project – was that supervision of the project passed from colonial officials to academic disciplinary specialists. In both Korea and Taiwan, a preliminary period of attempts at bureaucratically managed institutional projects was followed by one in which historians took control to develop more specialised projects involving archive compilation. The Japanese never abandoned their colonial projects, but they did make modifications. The new Taiwanese history project was entrusted to Murakami Naojirō, a leading historian in Tōkyō. He joined the Committee in 1923 to carry out research on the ancient history of Taiwan, meaning the period of European colonisations. At the Shiryō hensanjo where he worked, Murakami specialised in the history of international relations and the history of Spain and the Netherlands, the European powers that had colonised Taiwan in the seventeenth century.

Taihoku Imperial University takes control

Having been shelved in 1925, the project to compile a history of Taiwan was relaunched in 1929 by the new governor-general, Kawamura Takeji 川村竹治 (1871–1955, in office from June 1928 to July 1929). Supervision of the Committee (now called the Taiwan sōtokufu shiryō hensankai 臺灣總督府史料編纂會) was entrusted to Murakami, who by 1928 was a history professor at Taihoku Imperial University and became head of the Faculty of Literature and Politics in 1929. Under Murakami’s leadership, the history of the island’s colonisations definitively became the main focus of the project. The Committee’s new configuration placed it under the umbrella of the imperial university, making it part of a dynamic in which faculty staff from the History Department and members of the Committee largely overlapped.

MURAKAMI Naojirō

The aim was no longer to write a comprehensive history but rather to compile archives and historical documents following – as in Korea – the model of the Dai Nippon shiryō published by the Shiryō hensanjo11. The Committee’s new objective was to produce two sets of historical materials consisting of either recent or ancient sources, or of specialised studies. In concrete terms, these were: 1) the Taiwan shiryō 臺灣史料 (Historical Materials on Taiwan) series, known as kōhon 稿本 and kōbun 綱文, which focused specifically on Japanese rule since 1895 and ultimately comprised 51 volumes; and 2) the Taiwan shiryō zassan 臺灣史料雜纂 (Miscellaneous Historical Documents on Taiwan) series, presenting the colonial government’s archives and comprising 7 volumes12. Only three copies of the first series, Taiwan shiryō, appear to have been published and the originals are extremely rare13. In contrast to Korea, Japanese historiography in Taiwan perpetuated late-nineteenth-century biases by focusing on the period of Japanese rule, or at best the history of the European colonisations, events seen as marking the moment Taiwan truly “entered” history.

Taihoku Imperial University a few years after its inauguration

In fact, among all the corpora of archives and documents to be compiled, the 1929 archival project distinguished only between European or Manchu documents and Japanese documents. The historical events and dynamics of the period preceding the arrival of the Japanese were thus distinguished according to which power was attempting to control the island. The focus was not on the history of the island itself but of its domination: Taiwan’s Han populations were not considered worthy of interest and research on the aboriginal populations had been relegated to the field of anthropology, which also studied prehistory (as in Hokkaidō with the Ainu). This colonialist view in which all pre-colonial periods were seen as belonging to “pre-History” also existed in Africa and elsewhere in the Pacific, for example in New Caledonia.

The volumes on Japan, the Netherlands and Spain were supervised by Murakami, while those on China were overseen by Kubo Tokuji 久保得二, a professor who occupied the chair in East Asian Literature at Taihoku Imperial University. The composition of Taiwan shiryō zassan in particular, which was a compilation of miscellaneous sources and materials, reveals the interests of Murakami and his team and underscores his long-standing specialisation in Spanish and Dutch history14. Volume two of the series Taiwan shiryō zassan, for example, consists of a partial translation of the Daily Journals of Batavia Castle (Dagh-register gehouden int Casteel Batavia, Shōyaku Batavia-jō nisshi 抄譯バタヴィア城日誌)15, written by the governor-general of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in present-day Jakarta (the port of Anping in Taiwan was formerly a VOC trading post). The translated extracts focused on Japan and Taiwan in an attempt to illustrate the historical links between the two. This same topic was the subject of a lecture given by Murakami to the Society for the Study of Archives on Japan-Netherlands Exchange Networks (Tōkyō Nichi-Ran kōtsū shiryō kenkyūkai 東京日蘭交通史料研究會) in Tōkyō in 193716. Although other subjects more closely related to Japan were also studied, such as the history of Japanese trading posts, European-Manchu history remained the central theme: volume three presented the diary of the Dutch naval commander Cornelis Reijersz, who served in Asia from 1622 to 1624 and launched the construction of Fort Zeelandia (Anping port, present-day Tainan); while volume four presented sources relating to the Manchu domination of Taiwan in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Fort Zeelandia (Taiwan), seventeenth-century French engraving

Although the History of New Taiwan was replaced in 1929 by an archival project, two general reference works on Taiwan were published almost simultaneously. One was Inō Kanori’s vast posthumous work A Cultural Treatise on Taiwan (Taiwan bunka shi 臺灣文化志), published in 1928, which definitively blurred the boundaries between history and anthropology by stressing how artificial the distinction between them was in the context of colonial scholarship on Taiwan. Despite constant improvements in the technical quality of historical research, Inō’s work illustrates how little the angles of scientific inquiry had changed since 1900. The same can be said of the second work, Teikokushugi ka no Taiwan 帝國主義下の臺灣 (Taiwan under Imperialism)17, published in Japan in 1929 by Yanaihara Tadao 矢内原忠雄 (1893–1961)18. Yanaihara held the chair in Colonial Policy at Tōkyō Imperial University and was yet another researcher to focus on the Japanese colonial regime. After 35 years of colonisation, the content compiled in both Taiwan and the metropole showed the same concentration on the aboriginal question and a loss of interest in the history of the island itself.

But let us now turn our attention to the two imperial universities in the colonies and their history chairs.

3. The imperial university chairs and publications by colonial learned societies

Why create the colonial universities? Despite the apparent unity of Japanese imperial policy, the context in Taiwan and Korea was markedly different. To understand this, we need to widen our focus a little. In Taiwan, the hard sciences had always been dominant and the factors leading to the creation of the Faculty of Science and Agriculture at Taihoku Imperial University reflected a longstanding desire to merge the research facilities in place since 1895 in the field of agronomics, pharmacopoeia and tropical diseases. In 1909 these facilities were affiliated to the Taiwan Government-General Research Institute and then incorporated into the Central Research Institute (Chūō kenkyūjo 中央研究所) in 1921, when management of the hard sciences was centralised. In a sense, the policy adopted in Taiwan was characteristic of the interwar period and comparable to that of the USSR, the Republic of China and France19. It had no equivalent, however, in metropolitan Japan or Korea, where the regime’s main concern was to counter anti-colonial resistance.

The two imperial universities and colonial historiography

In February 1922, a revision of the ordinances governing education in Korea and Taiwan made it legally possible to open universities there, and for Koreans and Taiwanese to attend them20. Although the education systems in Korea and Taiwan were theoretically unified with that of Japan, they continued to be administered by the respective governments-general21.

In Korea in particular, the reform paved the way for local initiatives launched by the colonised peoples: in June 1922, the Society for Korean Education (Chosŏn kyoyukhoe 朝鮮教育會), headed by Yi Sang-jae 李商在 (1881–1927), took advantage of the newly relaxed legal framework to propose a national (i.e. Korean) university comprising four faculties in law, literature, economics and science22. This idea was discouraged by the colonial government, which restricted public fundraising appeals, and the project ended after the “convenient” disappearance of some of its backers. Nevertheless, such projects hailing from Korea’s independence movement drove Japan to create an imperial university there.

Keijō Imperial university

A preparatory school (Yoka daigaku 豫科大學) opened its doors in April 1924. Then in 1926, Keijō Imperial University (Keijō teikoku daigaku 京城帝國大學) opened a Faculty of Law and Literature (Hōbunka daigaku 法文科大學) and a Faculty of Medicine (Ika daigaku 醫科大學) with its own teaching hospital.

The Faculty of Medecine at Keijō Imperial university

Later, in 1941, the university was endowed with a Faculty of Science (Rikōka daigaku 理工科大學). In 1929 the university held 49 chairs in the Faculty of Law and Literature and 26 in the Faculty of Medicine, with a teaching body comprised of 70 professors and 43 associate professors, and a student body of around 500. The teaching and research undertaken by this university and its counterpart in Taiwan (see below) focused on “traditional” subjects, just as in Japan. Although students in the Faculty of Law and Literature’s History Department could take classes on China and Korea, the majority of courses covered general subjects like administrative law, the penal code, Western history, economic policy, diplomatic history, Russian, Ancient Greek and Latin23. In other words, these were universities “in a colonial context” rather than “colonial universities” per se. Korean students, who followed courses entirely in Japanese, represented around one third of the student body. This was a fairly high proportion for a colonial institution, compared, for example, to the University of Algiers under French colonisation24. However, they remained in inferior positions25.

In Taiwan, the decision to create an imperial university reflected the previously mentioned drive to centralise research in the hard sciences and also followed a similar move to institutionalise research in Korea. The Government-General of Taiwan decided to emulate Korea by creating a Japanese-style general university. Just like its Korean counterpart, however, Taihoku Imperial University (Taihoku teikoku daigaku 台北帝國大學), which opened in 1928, was not controlled by the Japanese Ministry of Education but by the colonial government26. It initially comprised two faculties: the Faculty of Literature and Politics (Bunsei gakubu 文政學部), and the Faculty of Science and Agriculture (Rinō gakubu 理農學部). In 1930, each faculty had 20 chairs. A Faculty of Medicine (Igakubu 醫學部) was created in 1936 and in 1938 it took over the running of the Taiwan Government-General Hospital, one of the oldest institutions in the colony. The influence of the war saw a Faculty of Technology (Kōgakubu 工學部) established in 1943, while the Faculty of Science and Agriculture was split into two separate entities27. Until the end of Taiwan’s colonisation, the research conducted at Taihoku Imperial University continued to have a southern, nanshin-ron 南進論 bias, referring to the doctrine advocating military expansion into South East Asia and the Pacific Islands, while the work carried out at Keijō Imperial University had a northern, hokushin-ron 北進論bias, reflecting the idea of a “Korea-Manchuria sphere”. The subjects explored by historical research in the colonies thus tended to extend into the neighbouring territories.

Between 1928 and 1937, Taihoku Imperial University was headed by renowned Oriental historian Shidehara Taira, introduced in the section on Korea. The two universities established in the colonies were elite institutions, open to a select number of students, as was generally the case prior to 194528. Taiwanese students represented a quarter of the student body in 1943, except in the Faculty of Medicine, where, as in Korea, they were more numerous29.

SHIDEHARA Taira

The history chairs at Keijō Imperial University, between Korean history and Japanese-Korean history

The creation of the Faculty of Law and Literature in Keijō, in 1926, saw two chairs in Korean History established: “Korean History Chair No 1” (Chōsen shigaku daiichi kōza 朝鮮史學第一講座), initially held by philologist and historian Imanishi Ryū, and “Korean History Chair No 2”, held by historian Oda Shōgo. When Imanishi died in May 1932, he was replaced the following month by archaeologist Fujita Ryōsaku, who had been an associate professor at the university since 1926 and was head curator at the Government-General Museum. As for chair number 2, it remained empty for several years following Oda’s retirement in November 1932 before being taken up in 1939 by Suematsu Yasukazu 末松保和 (1904–1992), a specialist in ancient Korea who had been an associate professor at the university and was a member of the Committee for the Compilation of Korean History30.

In parallel, the faculty also had two chairs in National History (Kokushigaku 國史學)31: the first was taken up by Tabohashi Kiyoshi 田保橋潔 (1897–1945) in 1927 and the second by Matsumoto Shigehiko 松本重彦 (1887–1969) in 1929. Both remained in their respective positions until 1945. Tabohashi was a historian of international relations and specialised in what was known as the “Far Eastern question”, meaning the history of the tensions between China, Korea, Japan, Russia and the Western powers since the mid-nineteenth century. This subject was also popular in France at the time, as evidenced by the mid-century work of Pierre Renouvin. The links between the metropole and the colonies are clear: Suematsu and Tabohashi both hailed from the Department of National History at Tōkyō Imperial University. Tabohashi, who graduated in 1921, had previously worked for the Committee for the Compilation of the History of the Meiji Restoration and at the Shiryō hensanjo. Keijō Imperial University also had two chairs in Oriental History, as well as a course in Western History as of 1941, taught by the specialist in French economic history Takahashi Kōhachirō 高橋幸八郎 (1912–1982), who was close to the Annales school of French historians32.

An Archaeological dig at Kongju (1908-1922).

According to the South Korean historian Cho Donggŏl, “a dual system took shape in which the Institute for the Compilation of Korean History was tasked with organising and disseminating primary sources and with presenting the colonial historiography to the population, while Keijō Imperial University was responsible for mass-producing books and articles validating this historiography”33. This needs qualifying however: although the colonial historiography did function according to just such an arrangement, the Chōsen shi project compiled by the Institute (mentioned in Part I) was perhaps more impressive for its volume than for its contents – which were simply a compilation of ancient sources – and as we shall see further on, the scholarly outputs of the various learned societies consisted either of general-public texts or of general overviews of a given subject. Finally, it was not only the Faculty of Law and Literature’s History Department that published a bulletin covering Korea and other cultural areas; the faculty’s three other departments also published bulletins to a greater or lesser extent in the field of Korean Studies (including linguistics).

The subjects explored as part of Korean history largely mirrored the questions examined by Japanese Oriental scholarship in the late nineteenth century. At the top of the list were the ancient history of Korea, the Chinese colonisation of Korea during the Western Han Dynasty (the Lelang Commandery, etc.) and the question of “Japan-Korea” relations (kankei 關係), notably with regards the “Japanese” protectorate of Kaya (Mimana) during ancient times34, and the invasions by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the sixteenth century35. Suematsu was an important figure in post-colonial Korean Studies and his role warrants a more detailed discussion than is possible here (for example, his post-1945 production of working indexes and bibliographies)36. Of the 94 dissertations submitted in Keijō’s History Department until 1943 – 37 of them by Korean students and 57 by Japanese – 33 focused on Korea37. No Korean students wrote a dissertation on national (i.e. Japanese) history.

In Taiwan: the history of colonial rule

At Taihoku Imperial University, the number of chairs in the Faculty of Literature and Politics evolved over the years within the four human and social science departments established in 1928: Philosophy, History, Literature and Politics. Three chairs were directly concerned with Taiwanese society. The general organisation of the chairs and focus of historical research were as follows38: The History Department (Shigaku-ka 史學科) initially had three chairs in Oriental History, History of the South Pacific (Nanyō shigaku kōza 南洋史學講座), and National History. To this was added a chair in Ethnology (Dozoku jinshu gaku kōza 土俗人種學講座), which was thus structurally linked to the History Department but focused exclusively on Austronesian aborigines39. Then in 1930 a chair in Western Historiography and Geography was established. This configuration and distribution of research responsibilities was specific to Taiwan. The three chairs in Ethnology, History of the South Pacific, and Anatomy No 2 (created in 1936) were devoted to studying Taiwan40. Finally, between 1934 and 1942 the Department published an annual report entitled Shigakuka kenkyū nenpō 史學科研究年報 (History Department Annual Report)41.

The only thing that set the imperial universities of the colonies apart from their metropolitan counterparts was the “local” focus of their research and their chairs dedicated to the colonial society and/or its history. They thus adopted, albeit at a later date, the same tripartite division of historical research seen in the metropole – national history, Oriental history and Western history – in addition to the chairs in “Colonial History”42.

The chair in the History of the South Pacific was assigned to Murakami in 1928, just as he was appointed head of the Committee for the Compilation of Historical Materials. He was assisted in his task by the associate professor Iwao Seiichi 岩生成一 (1900–1988), a specialist in the history of Japanese settlements and Japan-South East Asia relations, and by the lecturer Yanai Kenji 箭内健次 (1910–death unknown). Like Murakami, both were graduates of the History Department at Tōkyō Imperial University and Iwao had also worked as an assistant at the Shiryō hensanjo43. Murakami was initially sent in 1928 on a one-year study trip, financed by the Government-General of Taiwan, to the Netherlands, Great Britain, Spain, Portugal and the Dutch territory of Java.

At Taihoku Imperial University, Murakami, Iwao and Yanai were to study the history of the South Pacific, in other words, to expand the focus of research beyond the colonial conception of Taiwan’s history that had prevailed since the late nineteenth century and which had previously been limited to the period of Japanese rule. As previously noted, Murakami had a predilection for the history of the Dutch and Spanish colonisation of Taiwan44. Learning these two languages was thus an integral part of the South Pacific History curriculum. Murakami ultimately published some 120 works on the subject. He was also given the chair in Western Historiography and Geography when it was created in 1930. When Murakami left in 1935, the South Pacific chair was taken over the following year by Iwao, while the chair in Western Historiography and Geography was entrusted to Sugawara Ken 菅原憲 (dates unknown). Finally, the History Department’s research programmes sometimes involved anthropologists, who as we saw belonged to the same department. In 1937 for example, Utsushikawa Nenozō 移川子之藏 (1884–1947), who headed the chair in Ethnology, was sent to the National Archives of the Netherlands to photograph a substantial volume of documents relating to the Dutch colonisation of Taiwan in the seventeenth century.

This notwithstanding, the students themselves – some of whom were Taiwanese – changed the orientation of the South Pacific History section’s research outputs. This contrasted with the situation in Korea, where Korean scholars had their own research structures independent of the Japanese (see below). On the one hand, Murakami’s group focused exclusively on the history of the Dutch and Spanish colonisations of Taiwan and on the history of Japan’s relations with the European colonial powers present in South East Asia. The titles of the seminars taught on Murakami’s South Pacific History course, as presented in the faculty’s annual report, show a focus on the study of Spanish and Dutch documents and archives (which also concerned the Philippines), and on the study of these two languages (but emphatically not Chinese)45. On the other hand, as remarked by Taiwanese historian Chen Weizhi 陳偉智, who has studied the dissertations written by students on the course: among the thirteen graduates supervised by Murakami, Iwao and Yanai, four students (including one Taiwanese) wrote a dissertation on the history of seventeenth-century Taiwan proper, including two on the historical figure of Koxinga46. This shows that while the subject was generally avoided, it was not entirely supressed as it was after 1945 under Chiang Kai-shek.

Historical society publications on the “Blue Hills”

This final section provides a brief overview of the historical and philological societies linked to the colonial institutions, as well as their main publications47. Since figures are much more eloquent than a sterile inventory, suffice it to say that colonial Korea had no less than five major learned societies dedicated to Korean history, and while Taiwan once again cannot compare, it made up for it in the field of anthropology, which for fifty years was highly productive. Let us now look at some of the most significant publications of these societies, which will also shed light on the circulation of scholars among the different structures and institutions.

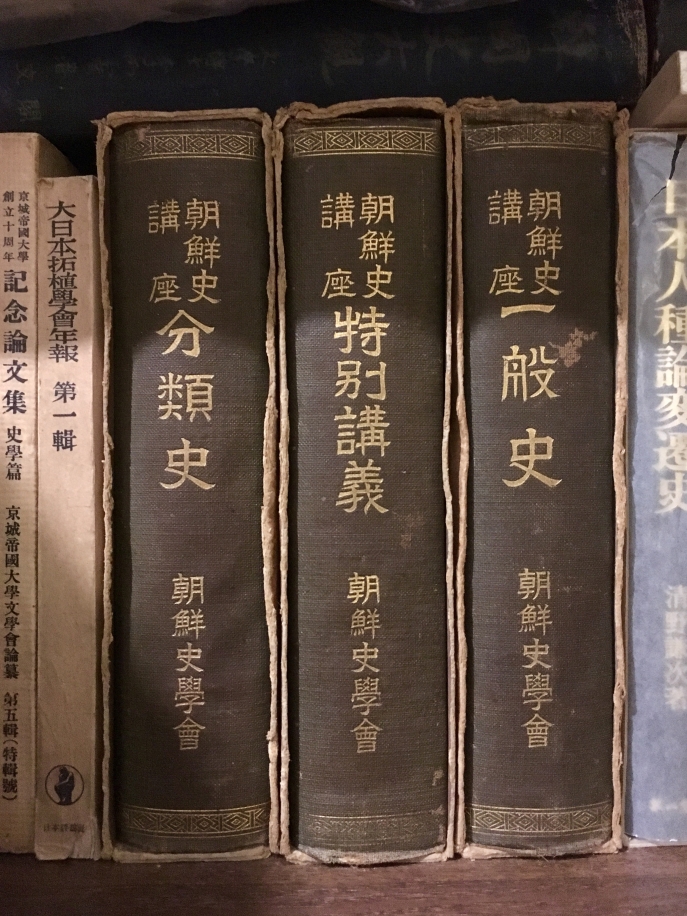

The most important of these societies was certainly Chōsen shi gakkai 朝鮮史學會, the Korean History Society, founded in 1923. Chōsen shi gakkai can be considered the first institutional learned society specialising in Korean history, all periods and research themes combined, although it is impossible to establish a link with the post-1945 period48. This society stood out for the number of collective works and reprints of older works it published. Headed by Oda Shōgo, then an official in the colonial government, its other members included historians Kuroita, Miura and Imanishi, architectural history specialist Sekino Tadashi 關野貞 (1868–1935)49, and Korean scholars50, giving the Chōsen shi gakkai an entirely official appearance. Nevertheless, unlike the Institute for the Compilation of Korean History, its research was not led from the top down and merits a more detailed presentation. It provides a much clearer picture of the academic face of the colonial historiography than the Chōsen shi produced by the Institute, which as we saw, was merely a annalistic compilation of documents.

From September 1923 to November 1924, Chōsen shi gakkai published its fifteen-part Korean History Lessons (Chōsen shi kōza 朝鮮史講座). These fifteen fascicules were originally distributed to members of the society but in 1924 were published in three volumes containing some forty lectures51. The proposed general outline for Korean history is set out in volume one. Although not fundamentally different from that proposed by Hayashi Taisuke in 1912, or by other early-twentieth-century works, in reality its contents were much more clearly defined. The colonial authors contributing to this 1924 publication also worked on the 1933–1935 book Japanese History Lessons, published by Iwanami, illustrating the esteem in which colonial research was held in the metropole (7 fascicules on Korean history out of a total of 130). Ultimately, the colonial historiography of Korea had a much greater presence in Japan than that of Taiwan (which was not included in the Japanese History Lessons series, for example).

The three volumes of Chōsen shi kōza

Another major work by Chōsen shi gakkai was the Compendium of Korean History (Chōsen shi taikei 朝鮮史大系), the title of a five-volume general history of Korea published in 1927. This extensive yet erudite textbook features references to books and academic journals from Japan and to archaeological reports and annexes in Chinese. The ancient periods (Lelang and the Three Kingdoms) are presented by Oda, with the rest of the compendium composed of manuscripts taken from Hantō-shi, notably texts by Seno and Sugimoto. Finally, there was the republication of the thirteenth-century Samguk yusa by Chōsen shi gakkai in 1928, under the supervision of historian Imanishi.

In conclusion: “colonial history” versus “national narrative”

The history of Taiwan and Korea was systematically studied throughout the entire colonial period, from the 1890s onwards. The period from 1890 to 1940 can be divided into several distinct phrases, as I have endeavoured to show in this paper. Work began during the pre-colonial period and was characterised by studies conducted by Oriental scholars (i.e. sinologists) from the metropole. This was followed by initiatives aimed at establishing general histories of Korea and Taiwan, and finally by the creation of institutions tasked with producing archival series. These endeavours culminated in the creation of specialised chairs at the colonial universities founded during the interwar period. The histories produced were “colonial” in the sense that they emanated from the colonising power and its agents, and concerned the colonised territories.

However, the question of the nature of this historiography has several possible answers. Generally speaking, Japanese academic scholarship in Korea and Taiwan can be described as having been produced “in a colonial context” rather than being specifically “colonial” in the sense of having some distinctive characteristic. Yet more than any other field, the colonial historiography was particularly prone to being imbued with a kind of “coloniality” due to its object of study and its commanding position over the colonised society, in a context where anti-colonial discourses were systematically invalidated.

In the empires of the modern era, colonial history was often synonymous with the history of colonial conquest, in other words, it resembled a “colonial epic”. This was the case in Africa52 and in much of the work carried out in Taiwan. The study of ancient worlds, notably in the Mediterranean, seemed on the face of it unrelated to the history of the colonised societies and connected instead with the history of earlier settlements. This was also true for the discovery of the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe (in what was then Rhodesia) in Sub-Saharan Africa53. In this context, the cases of Cambodia in Indochina and colonial Korea, where histories of the countries themselves were written – based on archaeology in Cambodia and a combination of historiography and archaeology in Korea – seem exceptional in the sense that genuine studies of the colonised society were undertaken. This in turn raises the question of the legacy of such research in the post-colonial era. In Korea, as in Indochina, the existence of an emminently ancient past, and the sense of their having a “mission”, captivated colonial scholars, who did not hesitate to compare the importance of their work, in particular on the Three Kingdoms (first to tenth centuries), to the research carried out in the Mediterranean.

The concept of Japanese colonial historiography thus actually points to two different realities in Taiwan and Korea. Nevertheless, as this paper has shown, Japan’s entire body of colonial historiography was part of a unified “system” that included metropolitan Japanese scholarship on East Asia and, as of the interwar period, the archive specialists at Tōkyō Imperial University’s Shiryō hensanjo. This configuration contrasts markedly with that, for example, of the French colonial empire, in that it involved a single network of scholars (mirroring its counterpart of colonial officials). Accordingly, studying Japanese colonial historiography means simultaneously studying modern Japanese historiography. It also reveals a distinctive feature of Japanese colonial scholarship, something only visible if we adopt an empire-level view, as I have attempted to do here. Doing so also raises the question of the links between colonial history and national history: the way these fields were established virtually simultaneously in Japan and the colonies, the way “national history” specialists from the metropole dominated scholarly networks in the colonies, the sharing of a common perception of history by coloniser and colonised, who paralleled each other in writing a “national narrative” type history, albeit with very different motivations.

Japanese colonial historiography ultimately appears to have been a means for the metropole to exert its power, regardless of the subjects examined. Indeed, the aim was as much to control what was written about the dominated society as it was to bring to a close the independent history of that country in order to facilitate its incorporation as a “region” of Japan. By definition, these two aspects were intertwined: only Japanese scholars were authorised to express their opinions, while dissenting voices were merely tolerated and anti-colonial ones were completely invalidated. All of these differing opinions resurfaced after Japan’s colonial empire was dismanteled in 1945, when a “decolonisation” of Japanese scholarship took place and Oriental Studies was divided into separate disciplines focusing specifically on Korea or Taiwan (for example via the Japanese Society for the Study of Korean History, founded in 1959). The post-1945 period also saw nationalist historiographies come to the fore, particularly in Korea, the only ex-colony to achieve independence, while Taiwan found itself absorbed by the Republic of China54.

►Access to the first part of the article:

Colonial Historiography in Taiwan and Korea under Japanese Rule, 1890s–1940s (Part I)

Notes

1

See: Wu Micha 吳密察, “Taiwan zongdufu xiushi shiye yu Taiwan fenguan guancang” 台灣總督府修史事業與台灣分館館藏 (Historical Works of the Taiwan Government-General and the Collection of the National Central Library’s Taiwan Branch), Taiwan fenguan guancang yu Taiwan shi yanjiu yantaohui 台灣分館館藏與台灣史研究研討會, Taipei, Guoli zhongyang tushuguan Taipei fenguan 國立中央圖書館台北分館, 1994a, 10, p. 39–72; Sakano Tōru 坂野徹, Teikoku Nihon to jinruigakusha 帝国日本と人類学者 (Imperial Japan and the Anthropologists), Tōkyō, Keisō shobō 勁草書房, 2005; Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35; Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Taibei diguo daxue yu jingcheng diguo daxue shixueke zhi bijiao (1926–1945)” 臺北帝國大學與京城帝國大學史學科之比較 (1926–1945) (A Comparison of the History Departments at Taihoku and Keijō Imperial Universities, 1926–1945), Taiwan shi yanjiu 臺灣史研究, Academia Sinica, 2009, 16 (3), p. 87–132.

2

Decree no 101, “Taiwan sōtokufu shiryō hensan iinkai kitei” 臺灣總督府史料編纂委員會規程.

3

The Committee was overseen by the Government-General of Taiwan’s Office of Compilation (Hensan-bu 編纂部).

4

Tahara was editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinpō 臺灣日日新報, published in Japanese and Chinese. Ozaki, who lived in Taiwan from 1901 to 1946, was head of the Chinese-language version. Zhong Shumin 鍾淑敏, “Taiwan riri xinbao hanwenbu zhuren Weiqi Xiuzhen” 臺灣日日新報漢文部主任尾崎秀真 (Ozaki Hotsuma, Head of the Chinese Section of Taiwan Nichinichi shinpō), Taiwanxue tongxun 臺灣學通訊, 2015, 85, p. 8–9.

5

For more on Ueda, see the detailed study by Lozerand Emmanuel, Littérature et génie national, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2005. Ogawa was later given the chair in Linguistics at Taihoku Imperial University when it was created in 1930.

6

Hiyama Yukio 檜山幸夫 et al. (eds), Taiwan shiryō kōbun臺灣史料綱文, Nagoya, Seibundō 成文堂, 1989, vol. 3, “Kaisetsu” 解説 (Exegesis), p. 325–477, specifically p. 354–355.

7

臺灣通史 Taiwan tongshi (Japanese reading: Taiwan tsūshi). This work collected and linearised earlier regional Chinese histories of Taiwan. For more information on the historical paradigms applied to Taiwan, see: Wu Micha吳密察, “Taiwan shi no seiritsu to sono kadai” 台灣史の成立とその課題 (The Constitution and Themes of Taiwanese History), in Mizoguchi Yūzō 溝口雄三 et al. (eds), Shūen kara no rekishi 周縁からの歴史 (History from the Fringes), Tōkyō, Tōkyō daigaku shuppankai, 1994b, p. 219–242.

8

Mochiji Rokusaburō 持地六三郎, “Shiryō hensan ni kan suru Mochiji hensan buchō no enjutsu” 史料編纂に關する持地編纂部長の演述 (Lecture on the Compiling of Historical Sources by Director Mochiji from the Office of Compilation), Taiwan jihō 臺灣時報, 1922, 37 (August), p. 23–26.

9

Mochiji Rokusaburō 持地六三郎, “Shiryō hensan ni kan suru Mochiji hensan buchō no enjutsu” 史料編纂に關する持地編纂部長の演述 (Lecture on the Compiling of Historical Sources by Director Mochiji from the Office of Compilation), Taiwan jihō 臺灣時報, 1922, 37 (August), p. 23–26, specifically p. 24.

10

Having worked in Taiwan from 1900 to 1910, Mochiji was posted to Korea in 1912 and remained there until 1920. He is a great example of the circulation of administrative staff within the empire. See: Kaneko Fumio 金子文夫, “Mochiji Rokusaburō no shōgai to chosaku” 持地六三郎の生涯と著作 (The Life and Work of Mochiji Rokusaburō), Taiwan kingendai shi kenkyū 台湾近現代史研究 (Journal of Modern and Contemporary Taiwanese History), 1979, 2, p. 119–128, in particular p. 120–121.

11

Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35, in particular p. 22.

12

Hiyama Yukio 檜山幸夫 et al. (eds), Taiwan shiryō kōbun臺灣史料綱文, Nagoya, Seibundō 成文堂, 1989, vol. 3, “Kaisetsu” 解説 (Exegesis), p. 325–477, in particular p. 330–333 and p. 414–415; Wu Micha 吳密察, “Taiwan zongdufu xiushi shiye yu Taiwan fenguan guancang” 台灣總督府修史事業與台灣分館館藏 (Historical Works of the Taiwan Government-General and the Collection of the National Central Library’s Taiwan Branch), Taiwan fenguan guancang yu Taiwan shi yanjiu yantaohui 台灣分館館藏與台灣史研究研討會, Taipei, Guoli zhongyang tushuguan Taipei fenguan 國立中央圖書館台北分館, 1994a, 10, p. 39–72, in particular p. 51; Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35.

13

These three copies are held at the National Central Library in Taiwan (Guojia tushuguan Taiwan fenguan 國家圖書館臺灣分館), the National Taiwan University Library, and in the East Asia archives at Kyōto University. The series was republished in the 1980s.

14

Wu Micha 吳密察, “Taiwan zongdufu xiushi shiye yu Taiwan fenguan guancang” 台灣總督府修史事業與台灣分館館藏 (Historical Works of the Taiwan Government-General and the Collection of the National Central Library’s Taiwan Branch), Taiwan fenguan guancang yu Taiwan shi yanjiu yantaohui 台灣分館館藏與台灣史研究研討會, Taipei, Guoli zhongyang tushuguan Taipei fenguan 國立中央圖書館台北分館, 1994a, 10, p. 39–72, in particular p. 51; Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35, in particular p. 22–23.

15

This book was republished by the Tōkyō-based company Heibonsha in three volumes between 1970 and 1975.

16

Tōhō gakkai 東方学会 (Institute of Eastern Culture) (ed.), Tōhōgaku kaisō 東方学回想 (Recollections of Eastern Studies), 9 vols., Tōkyō, Tōsui shobō 刀水書房, 2000, vol. 1; Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35, in particular p. 24–25.

17

Compare Yanaihara’s book to the series Lectures on the History of the Development of Japanese Capitalism, published in 1932–1933, which offered a much more objective analysis of Japan’s colonial rule. Akisasa Masanosuke 秋笹正之輔, Shokumin seisaku shi 殖民政策史 (History of [Japanese] Colonial Policy), in Hirano Yoshitarō 平野義太郎 et al. (eds), Nihon shihon shugi hattatsu shi kōza 日本資本主義發達史講座 (Lectures on the History of the Development of Japanese Capitalism), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1933.

18

For more on Yanaihara, see: Wakabayashi Masahiro 若林正丈, Teikokushugi ka no Taiwan seidoku 帝国主義下の台湾 精読 (Taiwan under Imperialism: Exegesis), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 2001; Souyri Pierre-François (ed.), Japon colonial, 1880–1930. Les voix de la dissension, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2014.

19

The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union was founded in 1925 (though its forerunner had a much longer history); Academia Sinica was founded in Nanking in 1928 and the CNRS, in France in 1939.

20

See: Abe Hiroshi 阿部洋, “Nihon tōchi-ka Chōsen no kōtō kyōiku” 日本統治下朝鮮の高等教育 (Higher Education in Korea under Japanese Rule), Shisō 思想, 1971, 565, p. 920–941, in particular p. 927–928; Chŏng Kŭnsik 정근식 et al., Singmin kwŏllyŏk kwa kŭndae chisik 식민권력과 근대지식 (Colonial Power and Modern Knowledge), Seoul, Seoul National University Press, 2011; Matsuda Toshihiko 松田利彦, Sakai Tetsuya 酒井哲哉 (eds), Teikoku Nihon to shokuminchi daigaku 帝国日本と植民地大学 (The Colonial Universities of Imperial Japan), Tōkyō, Yumani shobō ゆまに書房, 2014.

21

Article 12 of the revised ordinance made higher education institutions and universities subject to the same laws as in the metropole, placing them (theoretically) under the jurisdiction of the Japanese Ministry of Education.

22

A Preparatory Committee for the Society for the Creation of a National University (Millip taehak kisŏnghoe chunbihoe 民立大學既成會準備會) was established in November 1922. A fund set up in 1923 was highly successful and raised 150,000 (gold) Yen over the spring. The committee held its first general meeting in Keijō in March 1923, attended by more than 500 people, and a three-stage plan was adopted. See: Keijō teikoku daigaku dōsō-kai 京城帝国大学同窓会 (ed.), Konpeki, haruka ni 紺碧遙かに (Far Away, Deep Blue), Tōkyō, Keijō teikoku daigaku dōsō-kai, 1974, p. 3–9; Abe Hiroshi 阿部洋, “Nihon tōchi-ka Chōsen no kōtō kyōiku” 日本統治下朝鮮の高等教育 (Higher Education in Korea under Japanese Rule), Shisō 思想, 1971, 565, p. 920–941, in particular p. 927–936; Han Yongjin 韓龍震, “Il’che singmin t’ongch’i-ha ŭi taehak kyoyuk” 日帝 植民統治下의 大學教育 (University Education under Japanese Colonial Rule), Hanguk sa simin kangjwa 한국사 시민강좌, 1996, 18, p. 94–112, in particular p. 102–104.

23

See the annual report for 1941: Keijō teikoku daigaku 京城帝國大學 (Keijō Imperial University), Keijō teikoku daigaku ichiran 京城帝國大學一覽 (Keijō Imperial University Annual Reports), microfiches, National Library of Korea, 1924–1942, vol. 1941, p. 61–111.

24

See: Singaravélou Pierre, “L’enseignement supérieur colonial. Un état des lieux”, Histoire de l’éducation, 2009, 122, p. 71–92.

25

The Koreans published substantially within the Faculty of Medicine, where they wrote (or co-wrote) 13 percent of the faculty’s papers (35 out of 277). See: Chŏng Kŭnsik 정근식 et al., Singmin kwŏllyŏk kwa kŭndae chisik 식민권력과 근대지식 (Colonial Power and Modern Knowledge), Seoul, Seoul National University Press, 2011.

26

Imperial Decree no 30 “On Taihoku Imperial University” (Taihoku teikoku daigaku ni kan suru ken 臺北帝國大學ニ關スル件). Subsequent decrees set out its management (decree no 31), its faculties (decree no 32) and finally its chairs (decree no 33).

27

The Pacific War saw the university establish three specialised research centres, which were separate from the research units run by the chairs, in order to study the Pacific territories Japan hoped to exploit. These research centres in the hard sciences (Centre for Research in Tropical Medicine founded in 1939, Centre for Research on Southern Cultures and the Centre for Research on Southern Raw Materials, both founded in 1943) do not fall strictly within the bounds of the colonial period.

28

Wu Micha 吳密察, “Shokuminchi ni daigaku ga dekita!?” 植民地に大学ができた !? (A University in the Colony!?), in Matsuda Toshihiko, Sakai Tetsuya, Teikoku Nihon to Shokuminchi daigaku, Tōkyō, Yumani shobō, 2014, p. 75–105, in particular p. 93–94.

29

Ou Suying 歐素瑛, “Taihoku teikoku daigaku to Taiwan kenkyū” 台北帝国大学と台湾学研究 (Taihoku Imperial University and Research on Taiwan) in Kokusai kenkyū shūkai hōkokusho 国際研究集会報告書, 2012, 42, p. 19–37, in particular p. 23.

30

Keijō teikoku daigaku 京城帝國大學 (Keijō Imperial University), Keijō teikoku daigaku ichiran 京城帝國大學一覽 (Keijō Imperial University Annual Reports), microfiches, National Library of Korea, 1924–1942; Chŏng Kŭnsik 정근식 et al., Singmin kwŏllyŏk kwa kŭndae chisik 식민권력과 근대지식 (Colonial Power and Modern Knowledge), Seoul, Seoul National University Press, 2011, p. 349–350.

31

Initially, in 1927, there was only one; a second was created in 1928.

32

For the titles of the seminars that made up this course, see: Jang Shin 張信, “Kyŏngsŏng cheguk taehak sahakkwa ŭi chijang” 경성제국대학 사학과의 지장 (The Domain of the History Department at Keijō Imperial University), Yŏksa munjae yŏngu 역사문재 연구, 2011, 26, p. 45–83, in particular p. 79–81.

33

Cho Donggŏl 趙東杰, Hyŏndae hanguk sahak-sa 現代韓國 史學史 (A History of Historical Studies in Contemporary Korea), Seoul, Na’nam ch’ulp’an 나남출판, 2002, p. 271.

34

Suematsu Yasukazu 末松保和, Nikkan kankei 日韓關係 (Japan-Korea Relations), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1933.

35

Nakamura Hidetaka 中村榮孝, Bunroku, bunchō no eki 文祿・文長の役 (The Bunroku and Bunchō Era Invasions [by Toyotomi Hideyoshi]), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1935.

36

See in particular: Suematsu Yasukazu末松保和, Chōsen kenkyū bunken mokuroku 1868–1945 朝鮮研究文献目録1868–1945 (Bibliography of Materials in Korean Studies, 1868–1945), Tōkyō, Kumiko sho’in 汲古書院, 2 vols., 1980.

37

Jang Shin 張信, “Kyŏngsŏng cheguk taehak sahakkwa ŭi chijang” 경성제국대학 사학과의 지장 (The Domain of the History Department at Keijō Imperial University), Yŏksa munjae yŏngu 역사문재 연구, 2011, 26, p. 45–83, in particular p. 71–78.

38

Matsuda Toshihiko 松田利彦, Sakai Tetsuya 酒井哲哉 (eds), Teikoku Nihon to shokuminchi daigaku 帝国日本と植民地大学 (The Colonial Universities of Imperial Japan), Tōkyō, Yumani shobō ゆまに書房, 2014, p. 221–225; Wu Micha 吳密察, “Shokuminchi ni daigaku ga dekita !?” 植民地に大学ができた !? (A University in the Colony!?), in Matsuda Toshihiko, Sakai Tetsuya, Teikoku Nihon to Shokuminchi daigaku, Tōkyō, Yumani shobō, 2014, p. 75–105, in particular p. 93–94.

39

See: Sakano Tōru 坂野徹, Teikoku Nihon to jinruigakusha 帝国日本と人類学者 (Imperial Japan and the Anthropologists), Tōkyō, Keisō shobō 勁草書房, 2005.

40

This Anatomy chair (Kaibōgaku kōza 解剖學講座) was held by the physical anthropologist Kanaseki Takeo 金關丈夫 (1897–1983), whose work combined anthropology and prehistorical studies on Taiwan. Incidentally, a further chair in “Normal” Anatomy existed, held by the eldest son of the writer Mori Ōgai.

41

Taihoku teikoku daigaku Bunsei gakubu 台北帝國大學文政學部 (Taihoku Imperial University, Faculty of Literature and Politics), Shigakuka kenkyū nenpō 史學科研究年報 (History Department Annual Report), Taipei, 1934–1942.

42

Tanaka Stefan, Japan’s Orient, Berkeley, California University Press, 1993.

43

Under Murakami’s supervision, Iwao helped compile volume 12 of the Dai Nippon shiryō 大日本史料, which focused on Western sources. He undertook a three-month study trip in 1927 to China, Hong Kong, French Indochina, Siam and the Dutch East Indies. Having been appointed to his position in Taihoku (Taipei) in 1929, he was sent to Europe for a year and 10 months. See: Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35, in particular p. 10.

44

Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35, in particular note 31; Matsuda Toshihiko 松田利彦, Sakai Tetsuya 酒井哲哉 (eds), Teikoku Nihon to shokuminchi daigaku 帝国日本と植民地大学 (The Colonial Universities of Imperial Japan), Tōkyō, Yumani shobō ゆまに書房, 2014, in particular p. 261–279.

45

The titles of these seminars can be found in Taihoku teikoku daigaku Bunsei gakubu 台北帝國大學文政學部 (Taihoku Imperial University, Faculty of Literature and Politics), Shigakuka kenkyū nenpō 史學科研究年報 (History Department Annual Report), Taipei, 1934–1942: vol. 1934–1, p. 451–454, vol. 1935–2, p. 421, vol. 1936–3, p. 374; see the overview in Yeh Piling 葉碧苓, “Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu” 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (Murakami Naojirō’s Research on Taiwanese History), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 2008, 17, p. 1–35.

46

Ou Suying 歐素瑛, “Taihoku teikoku daigaku to Taiwan kenkyū” 台北帝国大学と台湾学研究 (Taihoku Imperial University and Research on Taiwan) in Kokusai kenkyū shūkai hōkokusho 国際研究集会報告書, 2012, 42, p. 19–37, in particular p. 25; Matsuda Toshihiko 松田利彦, Sakai Tetsuya 酒井哲哉 (eds), Teikoku Nihon to shokuminchi daigaku 帝国日本と植民地大学 (The Colonial Universities of Imperial Japan), Tōkyō, Yumani shobō ゆまに書房, 2014, in particular p. 280–281.

47

Cho Donggŏl 趙東杰 2002 Hyŏndae hanguk sahak-sa 現代韓國 史學史 (A History of Historical Studies in Contemporary Korea), Seoul, Na’nam ch’ulp’an 나남출판, 2002, p. 269–272; Yi Hyojin 李暁辰, Keijō teikoku daigaku no Kankoku jukyō kenkyū 京城帝国大学の韓国儒教研究 (Research on Korean Confucianism at Keijō Imperial University), Tōkyō, Bensei shuppan 勉誠出版, 2016.

48

The other learned societies are: Chōsen shi dōkō-kai 朝鮮史同攷會, the Society for the Study of Korean History, created in 1925 or 1926, which published the monthly bulletin Chōsen shi gaku 朝鮮史學 (Korean Historiography); Seikyū gakkai 青丘學會, the Blue Hills Society (Ch’ŏnggu, or Blue Hills, was an alternative name for Korea), founded in 1930 by members of the Faculty of Law and Literature, which published a seasonal bulletin called Seikyū gakusō 青丘學叢 (Blue Hills Bulletin), while the other bulletin published by the faculty was Konpeki 紺碧 (Deep Blue); Shomotsu dōkō-kai 書物同好會, the Society of Book Enthusiasts, founded in May 1937 by the archivist Sakurai Yoshiyuki 櫻井義之 (1904–1989), which published a bulletin called Shomotsu dōkō-kai kaihō 書物同好會會報 (see Sakurai’s postscript to the reprinted bulletin Shomotsu dōkō-kai kaihō); and the Korean society Chindan hakhoe 震檀學會 (the Chindan Society) founded in 1934 by Yi Pyŏngdo 李丙燾and others to counter the Seikyū gakkai (see Cho Kwanja 趙寛子, Shokuminchi Chōsen / Teikoku Nihon no bunka renkan 植民地朝鮮 / 帝国日本の文化連環 [The Cultural Links Between Colonial Korea and Imperial Japan], Tōkyō, Yūshi-sha 有志舎, 2007, chaps. 3, 4, 5). The Chindan Society published a bulletin entitled Chindan hakpo 震檀學報.

49

For more on Sekino, see: Nanta Arnaud, “L’organisation de l’archéologie antique en Corée coloniale (1902–1940)”, Ebisu, 2015, 52.

50

Cho Donggŏl 趙東杰 2002 Hyŏndae hanguk sahak-sa 現代韓國 史學史 (A History of Historical Studies in Contemporary Korea), Seoul, Na’nam ch’ulp’an 나남출판, 2002, p. 269.

51

Chōsen shi gakkai 朝鮮史學會 (ed.), Chōsen shi kōza 朝鮮史講座 (Korean History Lessons), Keijō, Chōsen shi gakkai (Korean History Society), 1924; Nanta Arnaud, Mémoire inédit à propos de l’histoire des savoirs coloniaux japonais en Corée colonisée et de Sakhaline entre les empires, HDR dissertation, Paris-Diderot, March 2017.

52

Dulucq Sophie, Écrire l’histoire de l’Afrique à l’époque coloniale (XIXe-XXe siècles), Paris, Karthala, 2009.

53

This site was initially attributed to a “pre-African” population when it was discovered in the second half of the nineteenth century.

54

I would like to thank Yi Sŏngsi at Waseda University, Takezawa Yasuko at Kyōto University, Misawa Mamie at Nihon University and Chen Haojia at Academia Sinica for their help with my research

Bibliographie

ABE Hiroshi 阿部洋, “Nihon tōchi-ka Chōsen no kōtō kyōiku” 日本統治下朝鮮の高等教育 (Higher Education in Korea under Japanese Rule), Shisō 思想, 565, 1971, p. 920–941.

AKISASA Masanosuke 秋笹正之輔, Shokumin seisaku shi 殖民政策史 (History of [Japanese] Colonial Policy), in HIRANO Yoshitarō 平野義太郎 et al. (eds), Nihon shihon shugi hattatsu shi kōza 日本資本主義發達史講座 (Lectures on the History of the Development of Japanese Capitalism), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1933.

BEASLEY William G., PULLEYBLANK Edwin G. (eds), Historians of China and Japan, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1961.

BERTRAND Romain, L’histoire à parts égales, Paris, Le Seuil, 2011.

CHEN Xiaochong 陈小冲, Riben zhimin tongzhi Taiwan wushi nian shi 日本殖民统治五十年史 (The 50-Year History of Japanese Colonial Rule in Taiwan), Beijing, Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe 社会科学文献出版社, 2005.

CHO Donggŏl 趙東杰, Hyŏndae hanguk sahak-sa 現代韓國 史學史 (A History of Historical Studies in Contemporary Korea), Seoul, Na’nam ch’ulp’an 나남출판, 2002.

CHO Kwanja 趙寛子, Shokuminchi Chōsen / Teikoku Nihon no bunka renkan 植民地朝鮮 / 帝国日本の文化連環 (The Cultural Links Between Colonial Korea and Imperial Japan), Tōkyō, Yūshi-sha 有志舎, 2007.

CH’OE Sŏg’yŏng 崔錫榮, Il’che ŭi Chosŏn yŏngu wa singminji-jŏk chisik saengsan 일제의 조선연구와 식민지적 지식생산 (Imperial Japanese Research on Korea and the Construction of Colonialist Perceptions), Séoul, Minsok-wŏn 민속원, 2012.

CHOI Kyongrak, « Compilation and publication of Korean historical materials under Japanese rule (1910-1945) », The developing economies, 7-3, 1969, p. 380-391.

CHŎNG Kŭnsik 정근식 et alii (dir.), Singmin kwŏllyŏk kwa kŭndae chisik 식민권력과 근대지식 (Colonial Power and Modern Knowledge), Seoul, Seoul national University press, 2011.

CHŌSEN KOSHO KANKŌ-KAI 朝鮮古書刊行會 Chōsen kosho mokuroku 朝鮮古書目錄 (Bibliography of Old Korean Books), Keijō, Chōsen zasshi-sha 朝鮮雜誌社, 1911.

CHŌSEN SHI GAKKAI 朝鮮史學會 (dir.), Chōsen shi kōza 朝鮮史講座 (Korean History Lessons), Keijō, Chōsen shi gakkai (Korean History Society), 1924.

CHŌSEN-SHI HENSHŪ-KAI 朝鮮史編修會 (The Institute for the Compilation of Korean History) (dir.), Chōsen-shi henshū-kai yōran 朝鮮史編修會要覽 (General Information on the Institute for the Compilation of Korean History), Keijō, Government-General of Korea , 1930.

CHŌSEN SHI HENSHŪ-KAI (dir.), Chōsen shi 朝鮮史 (The History of Korea), 36 volumes, Keijō,Government-General of Korea, 1932-1940.

CHŌSEN SHI HENSHŪ-KAI (dir.), Chōsen shi henshū-kai jigyō gaiyō 朝鮮史編修會事業概要 (Overview of the Institute for the Compilation of Korean History), Keijō, Government-General of Korea, 1938.

CHŌSEN SŌTOKU-FU 朝鮮総督府 (dir.), (Government-General of Korea) Chōsen hantō shi hensei no yōshi oyobi junjo 朝鮮半島史編成ノ要旨及順序 (Compiling the History of the Korean Peninsula: Objectives and Procedures), Keijō, Government-General of Korea, 1916.

DULUCQ Sophie, Écrire l’histoire de l’Afrique à l’époque coloniale (XIXe-XXe siècles), Paris, Karthala, 2009.

GUEX Samuel, Nouvelle histoire de la Corée des origines à nos jours, Paris, Flammarion, 2016.

HAKOISHI Hiroshi 箱石大, « Kindai Nihon shiryōgaku to Chōsen sōtoku-fu no Chōsen-shi hensan jigyō » 近代日本史料学と朝鮮総督府の朝鮮史編纂事業 (Archiving in Modern Japan and the Colonial Compilation of Korean History), in SATŌ Makoto 佐藤信 et alii (dir.), Zen-kindai Nihon rettō to Chōsen hantō 前近代日本列島と朝鮮半島 (The Japanese Archipelago and the Korean Peninsula in the Pre-modern Period), Tōkyō, Yamakawa shuppan-sha 山川出版社, 2007, p. 241-263.

HAN Yongjin 韓龍震, « Il’che singmin t’ongch’i-ha ŭi taehak kyoyuk » 日帝 植民統治下의 大學教育 (University Education under Japanese Colonial Rule), Hanguk sa simin kangjwa 한국사 시민강좌, 18, 1996, p. 94-112.

HAYASHI Taisuke 林泰輔, Chōsen tsūshi (Zen) 朝鮮通史(全)(The Complete History of Korea), Tōkyō, Toyama-bō 冨山房, 1912.

HÉMERY Daniel, BROCHEUX Pierre, Indochina. An Ambiguous Colonization 1858-1954, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011.

HIYAMA Yukio 檜山幸夫 et alii. (eds), Taiwan shiryō kōbun臺灣史料綱文, Seibundō 成文堂, Nagoya, vol. 3, « Kaisetsu » 解説 (Exegesis), 1989, p. 325-477.

INŌ Kanori 伊能嘉矩, Ryō Tai jūnen shi 領臺十年史 (A 10-Year History of Our Possession of Taiwan), Taipei, Niitaka-dō 新高堂, 1905.

JANG Shin 張信, « Kyŏngsŏng cheguk taehak sahakkwa ŭi chijang » 경성제국대학 사학과의 지장 (The Domain of the History Department at Keijō Imperial University), Yŏksa munjae yŏngu 역사문재 연구, 26, 2011, p. 45-83.

KANEKO Fumio 金子文夫, « Mochiji Rokusaburō no shōgai to chosaku » 持地六三郎の生涯と著作 (The Life and Work of Mochiji Rokusaburō), Taiwan kingendai shi kenkyū 台湾近現代史研究 (Journal of Modern and Contemporary Taiwanese History), 2, 1979, p. 119-128.

KASAHARA Masaharu 笠原政治, « Inō Kanori no jidai – Taiwan genjūmin shoki kenkyūshi e no sokuen » 伊能嘉矩の時代 台湾原住民初期研究への測鉛 (The Inō Kanori Era – Gauging the History of Early Research on Taiwanese Aborigines), Taiwan genjūmin kenkyū 台湾原住民研究 (Journal of Research on Taiwanese Aborigines), 3, 1998, p. 54-78.

KEIJŌ TEIKOKU DAIGAKU 京城帝國大學 (Keijō Imperial University) (ed.), Keijō teikoku daigaku ichiran 京城帝國大學一覽 (Keijō Imperial University Annual Reports), microfiches, National library of Korea, 1924-1942.

KEIJŌ TEIKOKU DAIGAKU DŌSŌKAI 京城帝国大学同窓会 (KTDD) (ed.), Konpeki, haruka ni 紺碧遙かに (Far Away, Deep Blue), Tōkyō, Keijō teikoku daigaku dōsōkai éd., 1974.

KIM Sŏngmin 김성민, « Chosŏn-sa p’yŏnsuhoe ŭi sosik kwa unyong » 朝鮮史編修會의 組織과 運用 (The Institute for the Compilation of Korean History: Organisation and Practice), Hanguk minjok undongsa yŏngu 한국민족 운동사 연구, 3, 1989, p. 121-164 ; Japanese translation in Nihon shisō-shi 日本思想史, 2010, 76, p. 7-60.

KUROITA Katsumi 黒板勝美, Kokushi no kenkyū sōsetsu 國史の研究 總說 (General Remarks on Studies in National History), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1931.

LOZERAND Emmanuel, Littérature et génie national, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2005.

MATSUDA Kyōko 松田京子, Teikoku no shikō. Nihon teikoku to Taiwan genjūmin 帝国の思考 日本「帝国」と台湾原住民 (The Logic of Empire. The Japanese Empire and Taiwanese Aborigines), Tōkyō, Yūshisha 有志舎, 2014.

MATSUDA Toshihiko 松田利彦, SAKAI Tetsuya 酒井哲哉 (eds), Teikoku Nihon to shokuminchi daigaku 帝国日本と植民地大学 (The Colonial Universities of Imperial Japan), Tōkyō, Yumani shobō ゆまに書房, 2014.

MIYAMOTO Nobuto 宮本延人, Inō Kanori shi to Taiwan kenkyū 伊能嘉矩氏と台湾研究 (Inō Kanori and his Research on Taiwan), Tōno shi kyōiku iinkai 遠野市教育委員会, 1971.

MOCHIJI Rokusaburō 持地六三郎, Taiwan shokumin seisaku 臺灣殖民政策 (Colonial Policy in Taiwan), Tōkyō, Toyama-bō 冨山房, 1912.

MOCHIJI Rokusaburō, « Shiryō hensan ni kan suru Mochiji hensan buchō no enjutsu » 史料編纂に關する持地編纂部長の演述 (Lecture on the Compiling of Historical Sources by Director Mochiji from the Office of Compilation), Taiwan jihō 臺灣時報, 37 (août 1922), p. 23-26.

NAKAMURA Hidetaka中村榮孝, Bunroku, bunchō no eki 文祿・文長の役 (The Bunroku and Bunchō Era Invasions [by Toyotomi Hideyoshi]), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1935.

NAKAMURA Hidetaka, « Chōsen shi no henshū to Chōsen shiryō no shūshū » 朝鮮史の編集と朝鮮史料の蒐集 (The Collection and Compilation of Archives on the History of Korea), in Nissen kankei shi no kenkyū 日鮮関係史の研究 (Research on the History of Japan-Korea Relations), Tōkyō, Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, vol. 3, 1969 [1964], p. 653-694.

NAKAYAMA Shigeru 中山茂, Teikoku daigaku no tanjō 帝国大学の誕生 (The Birth of the Imperial University), Tōkyō, Chūō kōron sha, 1978.

NANTA Arnaud, « Torii Ryūzō: discours et terrains d’un anthropologue et archéologue japonais du début du XXe siècle », Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, 22, 2010, p. 24-37.

NANTA Arnaud, « The Japanese Colonial Historiography in Korea (1905-1945) », in CAROLI Rosa, SOUYRI Pierre François (eds), History at Stake in East Asia, Venezia, Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina, 2012, p. 83-105.

NANTA Arnaud, « L’organisation de l’archéologie antique en Corée coloniale (1902-1940) », Ebisu, 52, 2015.

NANTA Arnaud, Mémoire inédit à propos de l’histoire des savoirs coloniaux japonais en Corée colonisée et de Sakhaline entre les empires, HDR dissertation, Paris-Diderot, March 2017.

OU Suying 歐素瑛, « Taihoku teikoku daigaku to Taiwan kenkyū » 台北帝国大学と台湾学研究 (Taihoku Imperial University and Research on Taiwan) in Kokusai kenkyū shūkai hōkokusho 国際研究集会報告書, 42, 2012, p. 19-37.

OZAWA Eiichi 小沢栄一, Kindai Nihon shigakushi no kenkyū. Meiji-hen 近代日本史学史の研究 (Study of the History of Modern Japanese Historiography: Meiji Period), Tōkyō, Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 1968.

SAEKI Arikiyo 佐伯有清, Kōkaido-ō hi to sanbō honbu 広開土王碑と参謀本部 (General Staff Office and the Question of King Kwanggaet’o’s Stele), Tōkyō, Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 1976.

SAKANO Tōru 坂野徹, Teikoku Nihon to jinruigakusha 帝国日本と人類学者 (Imperial Japan and the Anthropologists), Tōkyō, Keisō shobō 勁草書房, 2005.

SCHMID Andre, Korea Between Empires 1895-1919, New York, Columbia University Press, 2002.

SENO Umakuma 瀨野馬熊 (edited by NAKAMURA Hidetaka 中村榮孝) Seno Umakuma ikō 瀨野馬熊遺稿 (Posthumous Manuscripts of Seno Umakuma), Keijō, Chōsen insatsu-sha, 1936.

« SHIOKAWA » 鹽川, « Wagakuni to gaikoku to no kankei » 我國と外國との關係 (Relations Between our Country and its Neighbours), Kankoku kenkyūkai danwaroku 韓國研究會談話錄, 1, 1902, p. 1-8.

SINGARAVÉLOU Pierre, « L’enseignement supérieur colonial. Un état des lieux », Histoire de l’éducation, 122, 2009, p. 71-92.

SOUYRI Pierre-François, « L’histoire à l’époque Meiji: enjeux de domination, contrôle du passé, résistances », Ebisu, 44, 2010, p. 33-47.

SOUYRI Pierre-François, Histoire du Japon médiéval, Paris, Perrin, 2013.

SOUYRI Pierre-François (dir.), Japon colonial, 1880-1930. Les voix de la dissension, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2014.

SUEMATSU Yasukazu 末松保和, Nikkan kankei 日韓關係 (Les relations nippo-coréennes), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 1933.

SUEMATSU Yasukazu, Chōsen kenkyū bunken mokuroku 1868-1945 朝鮮研究文献目録1968-1945 (Bibliography of Materials in Korean Studies, 1868–1945), Tōkyō, Kumiko sho.in 汲古書院, 2 vols, 1980.

TAIHOKU TEIKOKU DAIGAKU BUNSEI GAKUBU 台北帝國大學文政學部 (Taihoku Imperial University, Faculty of Literature and Politics), Shigakuka kenkyū nenpō 史學科研究年報 (History Department Annual Report), Taipei, 1934-1942.

TANAKA Stefan, Japan’s Orient, Berkeley, California University Press, 1993.

TŌHŌ GAKKAI 東方学会 (Société des études orientales) (ed.), Tōhōgaku kaisō 東方学回想 (Recollections of Eastern Studies), 9 vols., Tōkyō, Tōsui shobō 刀水書房, 2000.

WAKABAYASHI Masahiro 若林正丈, Teikokushugi ka no Taiwan seidoku 帝国主義下の台湾 精読 (Taiwan under Imperialism: Exegesis), Tōkyō, Iwanami, 2001.

WU Micha 吳密察, «Taiwan zongdufu xiushi shiye yu Taiwan fenguan guancang » 台灣總督府修史事業與台灣分館館藏 (Historical Works of the Taiwan Government-General and the Collection of the National Central Library’s Taiwan Branch), Taiwan fenguan guancang yu Taiwan shi yanjiu yantaohui 台灣分館館藏與台灣史研究研討會, Taipei, Guoli zhongyang tushuguan Taipei fenguan 國立中央圖書館台北分館, 10, 1994a, p. 39-72.

WU Micha吳密察, « Taiwan shi no seiritsu to sono kadai » 台灣史の成立とその課題 (The Constitution and Themes of Taiwanese History), in MIZOGUCHI Yūzō 溝口雄三 et alii. (dir.), Shūen kara no rekishi 周縁からの歴史 (History from the Fringes), Tōkyō, Tōkyō daigaku shuppankai, 1994b, p. 219-242.

WU Micha, « Shokuminchi ni daigaku ga dekita !? » 植民地に大学ができた !? (A University in the Colony!?), in MATSUDA Tetsuya, SAKAI Toshikiko, Teikoku Nihon to Shokuminchi daigaku, Tōkyō, Yumani shobō, 2014, p. 75-105.

YEH Piling 葉碧苓, « Cunshang Zhicilang de Taiwan shi yanjiu » 村上直次郎的臺灣史研究 (La recherche en histoire taiwanaise réalisée par Murakami Naojirō), Guoshiguan xueshu jikan 國史館學術集刊, 17, 2008, p. 1-35.

YEH Piling, « Taibei diguo daxue yu jingcheng diguo daxue shixueke zhi bijiao (1926-1945) » 臺北帝國大學與京城帝國大學史學科之比較 (1926-1945) (A Comparison of the History Departments at Taihoku and Keijō Imperial Universities, 1926–1945), Taiwan shi yanjiu 臺灣史研究, Academia Sinica, 16 (3), 2009, p. 87-132.

YI Hyojin 李暁辰, Keijō teikoku daigaku no Kankoku jukyō kenkyū 京城帝国大学の韓国儒教研究 (Research on Korean Confucianism at Keijō Imperial University), Tōkyō, Bensei shuppan 勉誠出版, 2016.

YI Sŏngsi 李成市, « Koroniarizumu to kindai rekishigaku. Shokuminchi tōchika no Chōsen shi henshū to koseki chōsa o chūshin ni » コロニアリズムと近代歴史学 植民地統治下の朝鮮史編修と古蹟調査を中心に (Colonialism and Modern Historiography. The Compilation of Korean History and Surveys of Ancient Sites in Korea under Colonial Rule), in TERAUCHI Itarō 寺内威太郎 et alii, Shokuminchi to rekishigaku 植民地と歴史学, Tōkyō, Tōsui shobō, 2004, p. 71-103.

ZHONG Shumin 鍾淑敏, « Taiwan riri xinbao hanwenbu zhuren Weiqi Xiuzhen » 臺灣日日新報漢文部主任尾崎秀真 (Ozaki Hotsuma, Head of the Chinese Section of Taiwan Nichinichi shinpō), Taiwanxue tongxun 臺灣學通訊 85, 2015, p. 8-9.