(University of Zurich - Research Center for Social and Economic History (FSW))

Kunsthaus Zurich Chipperfield Building, Zurich.

“Zurich has shot itself in the foot”

On October 9, 2021, the Kunsthaus Zürich opened with great pomp and circumstance a new extension designed by British star architect David Chipperfield. The new building was erected on Heimplatz, facing the museum’s main building, which dates from 1910, and it showcases the Bührle Collection.1 This private loan from the Bührle Foundation comprises roughly two hundred paintings, including some world-famous Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, and it’s a first-rate crowd puller. The Kunsthaus website boasts that thanks to this world-class collection, Zurich now ranks “just below Paris.” Not only does Zurich now have the largest exhibition space in Switzerland, but the Bührle collection has catapulted the city into the top tier of the world’s museum cities.

There had already been a great deal of hubbub in the immediate run-up to the opening, with talk of a huge reputational risk. And indeed, the exuberance was short-lived. For no sooner had the golden gates of the new extension opened than all hell broke loose in the press. “A Nazi Legacy Haunts a Museum’s New Galleries,” headlined The New York Times.2 The article quotes the historian Erich Keller, whose book Das kontaminierte Museum3 immediately triggered international scrutiny, summing up the ghastly provenance of the Bührle trove in a nutshell: “It’s a collection built with money from arms sales, from slave labor, from child labor.”4 In mid-November 2021, bilan, a French-language business magazine published in Geneva, employed a mischievous metaphor to describe the fallout from the Bührle scandal: “Zurich has shot itself in the foot, not with a bullet, but with a cannonball.”5 The “cannonball” was an allusion to the German arms manufacturer Emil G. Bührle, who, from 1936 to the year of his death in 1956, had amassed his collection using profits from the production and sale of munitions, including massive supplies of arms to Nazi Germany until 1944. While Bührle’s story is fairly well known, the provenance of many of the paintings that ended up in his collection remains unexplored, and this is the aspect critics have zeroed in on.

Scandals have an unfortunate habit of fading away without repercussions. In this case, however, the controversy orchestrated by the media has led to some permanent changes. This article retraces the causes and consequences of that controversy, a raft of scandals in which several longer-term developments synergistically converged and came to a head. This wider backdrop has created optimal conditions to draw attention to the “Bührle complex,” in which the politics of national and local remembrance, the dynamics of the art market, provenance research and restitution practices are closely intertwined. The first three sections of this article outline the current controversy over the Bührle Collection. Section IV explains why this collection in particular has such a high potential for scandal, which involves a digression into the life of arms manufacturer and art collector Emil G. Bührle and his networks in the city of Zurich, the hub of the Swiss economy and finance. Section V recaps periodic criticism of the failure of post-war restitution efforts. Section VI retraces the tremendous expansion of international art markets and the parallel growth of provenance research since the 1980s. These developments, compounded by a rekindled awareness of the history of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, have fueled the debate about the restitution of looted art and, as shown in Section VII, have brought pressure to bear on private art dealers and public exhibitors and collections to address provenance issues previously swept under the rug. Section VIII concludes by pointing up the international consequences, unfinished business and unresolved issues stemming from the controversy in Zurich.

The Bührle Foundation fends off: science, politics and the public ask new questions

The Kunsthaus Zürich and the Bührle Foundation were surprised at the vehemence of the criticism attending the Bührle Collection opening in the new Chipperfield extension. After the Bührle family in the late 1990s claimed that no documents were left with which to trace the collection’s provenance, the Bührle Foundation suddenly discovered an archive and began provenance research under its new director, Lukas Gloor.6 The assumption underlying these inquiries was that the Swiss art trade between 1933 and 1945 was conducted by and large according to the rule of law, so all participants in market transactions were acting with full freedom of agency and no sales were made under pressure or duress. And that, where there was any sense of uncertainty about the exact origin of a work, the acquisition was bona fide, thereby divesting restitution claims of any moral or legal basis.

In a word, the Bührle Foundation thought it was “in the clear.” For the grand Kunsthaus opening in 2021, the Swiss Institute for Art Research came out with a comprehensive report on the Bührle Collection: in the foreword, foundation members who had financed the report lauded the “painstaking scholarly research” that went into the earlier catalogs and could now be considered completed.7 Lukas Gloor, the lead author, regretted that the collection has been viewed since the turn of the millennium “mainly in terms of looted art and the arms trade.” Brushing off critical objections, he claimed that “full verification” had been carried out in contentious cases, thereby averting any “risk that the Emil Bührle Collection might become a political liability for the Kunsthaus.”8

Braced by this robust reassertion of a self-assurance steeled by fending off criticism for several decades, the Bührle Foundation and the Kunsthaus at first summarily rebuffed the challenges that had resurfaced, which the leading media increasingly came to regard as an inability or unwillingness to learn from past mistakes.

But all that changed during a disastrous press conference held by the Kunsthaus on December 15, 2021. Instead of clearing up the situation, the director of the museum ended up having to walk back false statements. The local press coverage took a harsher line. In early 2022, Swiss painter Miriam Cahn accused the Kunsthaus of “artwashing” and announced her intention to buy back her works on exhibit there.9 In the Tagesanzeiger, the leading Zurich daily, one commentator wrote, “Why not turn the Chipperfield building into a Swiss memorial to Switzerland’s complicated entanglements with Nazi Germany?”10

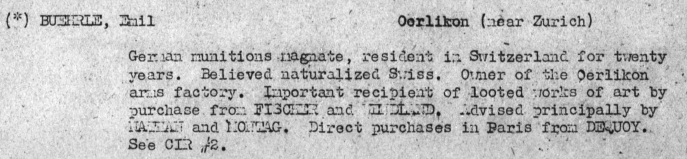

ALIU Final Report Red Flag List of Names 1945-6 Entry for BUEHRLE, Emil NARA M1782 Record Group: RG 239 Roll: M1782_10F1.

Text: “Buehrle, Emil. Oerlikon (nr Zurich). German munitions magnate, resident in Switzerland for twenty years. Believed naturalised Swiss. Owner of the Oerlikon arms factory. Important recipient of looted works of art by purchase from Fischer and Wendland. Advised principally by Nathan and Montag. Direct purchases in Paris from Dequoy.”

Past calls for transparency, including recurrent demands by the leftist Alternative List, the Green Party and Social Democrats in the communal and cantonal parliaments since 2012, have returned to the fore in recent years. In late 2020, the IG-Transparenz (“Transparency Alliance”) started up a petition entitled “Licht in die Kunstsammlung Bührle” (i.e. to shed “light on the Bührle Collection”), which was submitted to Zurich’s Mayor Corine Mauch in January 2021 with 2,300 signatures. The petition called on the mayor and the Kunsthaus to disclose the – previously secret – terms of the loan agreement and to investigate and disclose the provenance of the entire collection. Furthermore, a research team under the direction of Matthieu Leimgruber at the University of Zurich’s history department put together a study in late 2021 on Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus (“War Profiteering, Capital and Kunsthaus”).11 Erich Keller’s combative book about the “contaminated museum” came out with a bang at a big launch held just weeks before the inauguration of the new Kunsthaus extension. And Heinz Nigg’s book cum video documentary came out that year too: entrechtet – beraubt – erinnert (“disenfranchised – despoiled – remembered”) tells the stories of various victims of Nazi persecution and spoliation, including women forced to labor in Bührle’s arms factories in Nazi Germany.12

To channel public outrage, former members of the “Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War” (ICE for short, also known as the “Bergier Commission” after its president, Jean-François Bergier) put out a much-publicized statement in the press in mid-November 2021, making three demands: First, the “documentation room” providing information about the history of the collection should be overhauled to incorporate the latest research findings. Second, the entire collection and the Bührle Foundation previous pro domo provenance research should be reviewed for cases of “property seizure resulting from Nazi persecution.” And third, a national commission should be set up to look into restitution claims in accordance with international law.13

Chronicle of an announced scandal

Why did the “red-green” coalition that has reigned over the Swiss “capital of secrecy” for three decades now ignore criticisms of the Bührle Collection for so many years? And why did they disregard all the telltale signs that opening this collection up to the general public was not going to be a matter of business as usual? After all, Friedrich Christian Flick was sent packing in 2001 when he tried to open a museum in Zurich for his contemporary art collection. His plan was rejected owing to his grandfather Friedrich Flick’s Nazi past and the dubious origins of the family fortune.14

So there was clearly some awareness of the historical problems with these tainted legacies, but the troublesome past was hushed up when it came to the personal networks linking Zurich finance to its art scene via the tax base, philanthropy and the elitist behavior of the traditional urban guilds. Bührle’s “involvement in the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft” from 1940 on and “the connections between Bührle’s financial, cultural and political activities,” even long after World War II, are documented in the aforementioned historical study.15 The Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft, the organization that runs the (publicly funded) Kunsthaus, serves as an interface between various sectors of the economy. Since World War I, its presidents have all come from major banks, insurance companies, or both, with close ties to industrial companies. From 1987 to 2021, all the presidents were from Credit Suisse or Swiss Re.16 Since 2022, the position has been held by Philipp Hildebrandt, who was president of the Swiss National Bank until 2012 and has since served as vice chairman at the global asset manager BlackRock.

Notwithstanding Emil G. Bührle’s close ties to the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft, his collection was not integrated into the Zürcher Kunsthaus. He died suddenly in 1956 without leaving a will, and in 1960 his heirs decided to display the valuable paintings in the family villa, a makeshift arrangement that remained unchanged for several decades. So the Bührle Collection received relatively little attention and led a wallflower existence on the outskirts of Zurich. At the dawn of the 21st century, there was still no end in sight to this untroubled state of affairs.

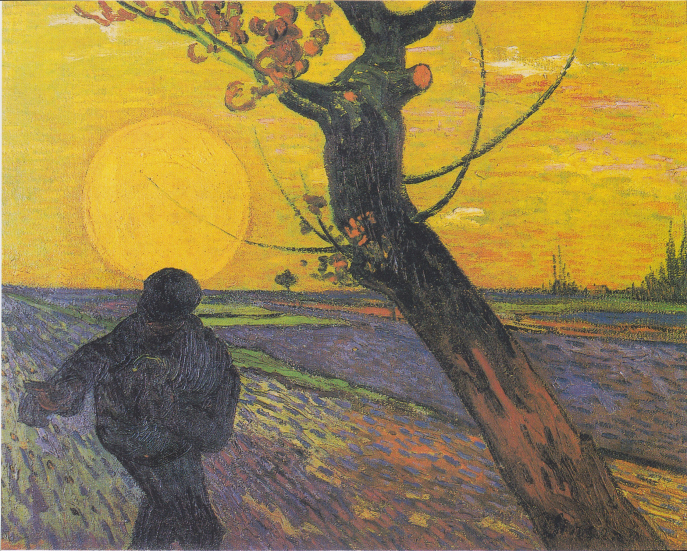

Sower at Sunset, Vincent van Gogh, 1888. Emil Bührle’s Collection.

But Zurich was rudely awakened from its slumbers on February 10, 2008, when armed robbers stole four of the most valuable paintings – a Cézanne, a Van Gogh, a Monet and a Degas – from the poorly protected private museum. It was probably the biggest art heist in Europe to date: the media reported in astonishment that these four works alone were worth 180 million Swiss francs.17 Hence the subsequent plan to transfer the Bührle Collection to the Kunsthaus Zürich. Eager to play this trump card, the city issued a call for architectural proposals, which David Chipperfield won with his massive cube.

On November 25, 2012, 54 percent of Zurich voters came out in favor of the cube. Right-wing parties, especially Christoph Blocher’s xenophobic Swiss People’s Party, vehemently opposed the CHF 206 million plan, 43 percent of which was to be funded by private donations. Bourgeois liberals and the social democrats, on the other hand, championed this ambitious cultural project as a matter of local political pride.18 And the media played up the competitive edge the collection would give Zurich vis-à-vis other European cultural capitals.

But critics of the collection did not fall silent. No sooner had the diggers shown up at Heimplatz in 2015 than the Schwarzbuch Bührle (“Bührle Black Book”) came out, tracing the historical background of the arms manufacturer and his collection and pointing out unresolved restitution issues.19 The book was based on a substantial amount of preliminary research. A team of authors had provided an initial overview in the Bührle Saga back in 1981.20 Historian Thomas Buomberger began investigating the problem of looted art in Swiss museums in the 1990s.21 As part of the research conducted by the ICE, a two-volume report by Peter Hug was published in 2001 along with other ICE studies on looted art and the Zurich financial hub.22 So there was an abundance of available information to pave the way for a critical look at the arms manufacturer Emil G. Bührle and his art collection. But suchlike warnings were successfully marginalized in Zurich’s political context and routinely faded away without any effect.

Bührle bust in the new building from 1958 (financed by Bührle).

Emil G. Bührle: the arms dealer and art collector in the eye of the hurricane

The rise of arms magnate Emil G. Bührle in the 1920s and ’30s roughly paralleled the emergence of the Swiss financial industry as a hub of international asset management. The groundwork had been laid in the years following World War I. In Germany, an attempt to foment a democratic revolution was put down at gunpoint by right-wing Freikorps volunteers. Emil Georg Bührle, who was 28 years old at the time, marched with General von Roeder’s notorious “Freiwilliges Landes-Schützen-Korps,” who had assassinated Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in January 1919. Neutral Switzerland, spared the ravages of the war, had become a magnet for capital flight, holding companies and direct investors. Emil Georg Bührle was sent to Zurich by Magdeburger Werkzeugmaschinenfabrik, which had bought Werkzeugmaschinenfabrik Oerlikon (WO) in 1923. A year later, WO took over the insolvent Seebach machine factory and came into possession of its patent on a 20-millimeter canon, on which he had probably set his sights from the outset. In 1929, Bührle, now the principal shareholder, consolidated his control over WO, whose canon had long since become its key sales driver. Like other neutral countries (Sweden, Netherlands), Switzerland was a paragon of German offshore arms production, and WO contributed significantly to the clandestine rearmament of the paramilitary “Black Reichswehr” – thereby circumventing the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles and constituting a violation of international law.23

Bührle’s business really took off when Hitler unleashed World War II and the German Wehrmacht advanced across Europe. By 1944, he had delivered CHF 540 million worth of weapons to the Axis powers, corresponding to 70 percent of Switzerland’s total arms exports. From 1941 on, a large part of this business was financed directly by the Swiss state treasury via what was known as the “clearing billion,” thereby breaching the law of neutrality. Thanks to these state subsidies, Bührle soon became the richest man in Switzerland, rounding off his profits with licenses to exploit forced labor in Germany and later on diversifying into the Swiss textile industry, in which the miserable working conditions were exacerbated by the imposition of forced labor.24

Although he was blacklisted by the Allies, that did not keep him from patronizing the arts in Zurich (and other Swiss cities, including Lucerne). While he ultimately failed to gain sway over the anti-fascist Zurich Schauspielhaus (also known as the “Pfauenbühne” or “Peacock Theater”), he did make inroads at the Kunsthaus and had been buying up works of art since 1936. He became a Swiss citizen in 1937, took a seat on the collection committee of the Kunstgesellschaft in 1940, and in 1942 he promised to build a big modern museum wing. But criticism of the arms industrialist’s financial showmanship and outsize influence on Zurich’s arts policy began to mount towards the end of the war. In February 1945, the anti-fascist newspaper Die Nation denounced Bührle as “the biggest and most unscrupulous war profiteer in our country” and described his millions as “blood money from the first to the last centime.”25 By the end of the war he had acquired 146 artworks.

Under massive Allied pressure, the Swiss Federal Council issued a “Raubgutbeschluss” (looted property decree) on December 10, 1945, and the Federal Supreme Court created a “Raubgutkammer” (looted property court) to adjudicate restitution claims. Emil G. Bührle had to restitute thirteen paintings, nine of which he immediately bought back in 1951. Not only that, but because the Federal Court – in blatant disregard for the facts – recognized his claim of “bona fide acquisition” of this looted art, the state had to help defray Bührle’s “restitution costs.”

By the end of the 1940s, the Cold War had already begun and Bührle’s arms factory was now banking on supplying armaments for the Pax Americana. Beginning in 1951, he supplied some 250,000 powder rockets for the Korean War and systematically expanded his markets. He traveled to the US several times and purchased first-rate paintings in New York and London. The bulk of his collection, which would ultimately count 638 works, dates from this period. When Bührle died unexpectedly in 1956, the extension he had financed was not yet operational. It was ceremoniously opened two years later with an exhibition of part of his collection. But, as mentioned above, the much-anticipated donation to the Kunsthaus failed to materialize. In 1960, the Bührle family established a private foundation to hold nearly a third of the collection: 203 items, mainly paintings, including the cream of the crop. This Bührle Collection is the bone of contention today because it is held in a publicly funded museum, but there may well be unresolved restitution issues regarding the rest of the collection, which is large and hardly vetted to date, and which has remained the non-public property of the Bührle family.26

Switzerland as a hub for looted art and long-term ramifications

During the Nazi era, neutral Switzerland played a central role as a hub of the trade in art and other cultural goods, especially looted art and Fluchtgut or “flight assets.” A number of German collections of paintings were relocated to neutral territory, with a number of savvy art dealers following in their wake. The Fides Treuhand-Gesellschaft, a trust company owned by the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (SKA, which later became Credit Suisse (CS)), served as the key cog in the financial machinery for the transactions.27 Some auction houses, in particular the Galerie Fischer in Lucerne, handled large-scale barters, especially with the Göring collection and Hitler’s collection for his pet “Führermuseum” project in Linz. Through these works and deals, the “loot” resulting from Nazi practices of disenfranchisement, persecution, spoliation and extermination found its way into Switzerland. Bührle profited in equal measure from the armaments boom and from plundered art. War, capital accumulation and the looting and collecting of art are, as it turns out, complementary pursuits.28

By early 1943, if not before, when the Allied powers warned that after the Wehrmacht’s unconditional surrender, any business transacted with Nazi Germany would be declared null and void, anyone amassing artworks at the time knew the risks involved. But the spoliation of cultural assets resulting from Nazi persecution remained a widespread problem even after 1945. Allied Military Government Law No. 52 concerning the “Blocking and Control of Property,” which remained in force until the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, continued to prohibit all transactions involving “significant artworks or cultural objects.”29 Nevertheless, according to one Swiss legal expert, “More looted art was probably traded in the first post-war years than during the war, for the actual trade took off immediately after the Second World War, when the stolen works entered the art market.” Purchases of art during this period clearly could not presumed to be “bona fide acquisitions,” but this fact was suppressed in Switzerland.30

Paintings were not the focus of restitution efforts in the early postwar period, however. In order to identify cultural property whose former owners had been murdered, Jewish Cultural Reconstruction (JCR), Inc. published from 1946 to 1948 a “Tentative List of Jewish Cultural Treasures in Axis-Occupied Countries,” which included 854 newspapers and magazines, 643 Jewish publishing houses, 430 Jewish libraries and roughly 3.5 million written documents that had been either destroyed or stolen and in any case could no longer be located. Armed with this list, Hannah Arendt, who was JCR’s executive director at the time, traveled to Germany in 1949, still a stateless Jew at the time, and negotiated with US authorities as well as with German librarians and museum administrators. Central to this investigation was the reconstruction of Jewish writing and book culture.31 From 1951 onwards, the Jewish Claims Conference represented the restitution claims of Jewish victims of National Socialism and survivors of the Shoah, focusing on plundered companies, shareholdings, real estate and other assets.

Swiss courts paid scant attention to these issues during the postwar period.32 As far as the “art trade’s duties of diligence” were concerned, “no added requirements” were imposed, as an IEC legal expertise noted in 2001.33 Like other objects of value, such as automobiles and refrigerators, works of art and cultural assets could be purchased or resold in the first three decades after World War II without having to inquire about their origin. But that became more difficult in the 1980s, when the number of transactions increased and prices curved steeply upwards. In 1987, for example, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court required dealers in used vehicles (especially sports cars and limousines, which were often stolen by gangs) to “exercise greater due diligence in their business” and to be “particularly careful” when acquiring such automobiles.34

Price explosion on art markets and the rise of provenance research

In the 1980s, prices exploded on the art markets, too. Art sales increased in aggregate value over seventy-fold from the 1970s to the 2010s. So it was only logical to extend “this jurisprudence on stiffer due diligence requirements for used car dealers [...] to the art trade,” as occurred in 1996 in a Federal Court decision on a case in the antiques trade.35 The stiffer due diligence standards were not due to a heightened historical awareness, but had far more to do with increased income and wealth inequalities at the global level and within nations, which in turn was propelled by the rise of financial market capitalism and the concomitant financialization.36 The growing demand for art reflected efforts to diversify investment portfolios as well as a penchant for cultural self-stylization among the nouveaux riches. It spurred a spectacular increase in the number of high-turnover art galleries and the turbulent expansion of art markets. Artistic creativity and processes of economic value creation were intertwining in a new way.37

The Offering, Paul Gauguin, 1902. Emil Bührle’s Collection.

As art historian Philip Ursprung noted, “The art market, which had been vibrant since the 1980s, increasingly became the focus of public attention after a crash in 1991, and even hedge fund managers began trading in artists as if they were stock portfolios.” It was precisely the crises of those years that prompted purchases of cultural goods: “While the financial economy was collapsing and threatening to drag the real economy down with it, the art market was flourishing more than ever.”38 The upshot was a rush to invest in artworks with high recognition value: the prices for “Impressionists” in the broadest sense (i.e. including Gaugin, Van Gogh, Cézanne, Degas, etc.) went through the roof, as did the Old Masters. These investors had an interest in knowing the precise provenance of an artwork before buying it. As a result, art historical expertise served to grease the workings of a buzzing art market.

Under these conditions, provenance research served more to secure investments than to right past wrongs. The demand for this service shot up as precipitously as the prices for high-caliber artworks. Emil G. Bührle’s collection, too, reaped the benefits of this meteoric growth in value, this tremendous enrichissement.39 From 1936 to 1956, he spent a total of about CHF 40 million (equivalent to CHF 300 million today) on his collection. The six hundred works were assessed for tax purposes at a derisory CHF 10 million in 1957. Their present-day value runs into the billions. The 203 paintings that were included in the collection established in 1960 that came to be known as the “Sammlung Bührle,” the ones now on display in Zurich, are worth roughly CHF 3 billion today. The fact that the entire collection is still in private hands is a matter of some concern. The viewable part of the collection is covered by a loan agreement that was renewed and made public in 2021, but which could be terminated as early as 2034. All the rest, around two thirds of the works collected by Bührle, is the exclusive domain of his heirs. The image of the altruistic philanthropist letting society share in the fruits of his labor is misleading. It can be assumed that the prominent display of the Bührle Collection at the Kunsthaus, which is subsidized with tax money, will trigger a win-win process that serves to increase its value in the private sector. And provenance research will do its part to buttress that value.40

On the other hand, since the entire collection was amassed during the Nazi era and the first decade after the war, closer scrutiny of the paintings’ provenance also contributed to transitional justice from the 1990s on. Public awareness of the “Final Solution,” a historically unique crime against humanity involving the persecution and extermination of European Jewry and resulting in the relocation of all kinds of property on an unprecedented scale, was rekindled towards the end of the Cold War – partly thanks to the American television series Holocaust broadcast in 1979.41 Switzerland, which has a long-standing tradition of repressing its entanglements, connivance and collusion with Nazi Germany, could not escape that development. In 1996, a full-blown foreign policy crisis broke out when, despite compelling evidence, Swiss banks continued to refuse to finally address the problem of so-called “dormant assets” resulting from the Holocaust. Throughout the post-war period, inquiries into restitution claims were suppressed or, if unavoidable as in the 1960s, pursued perfunctorily with minimal investment of time and effort. Now, however, the Swiss parliament and government felt compelled to appoint an Independent Commission of Experts (ICE) to investigate not only the issue of dormant assets, but also looted gold, Swiss companies’ involvement in forced labor and Aryanization, and Switzerland’s anti-Semitic refugee policy. Furthermore, in-depth studies came out on the connection between clandestine financial operations and the art market, including the trade in looted art.

The ICE study Flight Assets/Looted Assets, published in 2001,42 was backed up by previous research, in particular Lynn H. Nicholas’s groundbreaking 1994 study “The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War.” More and more private collectors and museums were faced with restitution claims. A 1990 exhibition of some masterpieces from the Bührle collection at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, had provided a foretaste of the controversies to come.43 Art critic Michael Kimmelman wrote bluntly at the time that the museum “should never have undertaken” the exhibition. “The point is not that these works shouldn’t be seen, but that they should be seen in a meaningful context.”44 And this context was by no means outside the art world, but a whole raft of problems that permeated and caused multiple shocks within the art world.

Special exhibition at Museum Wallraf-Richartz: “Von Dürer bis Van Gogh-Sammlung Bührle trifft Wallraf (From Dürer to van Gogh – the Bührle Collection meets Wallraf).”

The impact of the Washington Principles (1998)

So it was to be expected that the question of Nazi plunder would increasingly beset museums, policymakers and the courts over the course of the 1990s. The Swiss ICE pointed out, in particular, parallels between looted art and dormant assets45: just as the money in these dormant accounts was kept by the banks after World War II, so, too, did artworks become “dormant” and end up being retained by their new owners. In both cases, serious research was obstructed and even prevented for over half a century.

After the Cold War, however, this debate gained international momentum. At the 1998 Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets, a set of principles under international (soft) law was negotiated – in which the Swiss representative played a significant part – to achieve “just and fair solutions.”46 These principles were confirmed in Terezín in 2009 and the term “Nazi-confiscated and looted art” was made binding in order to prevent so-called “flight assets” from continuing to be regarded as unproblematic and kept out of inquiries. As a result, the approach taken by Switzerland, which had hitherto considered itself to be on the “safe side” with regard to restitution claims (and had dismissed inquiries), became anachronistic and untenable – all the more so as the Kunsthaus Zürich is a member of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and a signatory to the Washington Declaration. These international legal norms are so-called “soft law,” they allow considerable wiggle room in their implementation at national level. While many countries have created restitution commissions, some of which can make recommendations and others binding decisions, Switzerland has merely set up a “contact point” at its Federal Office of Culture. In the meantime, the government supports, at least in principle, a parliamentary motion submitted in late 2021 calling for the creation of a Swiss commission on Nazi-confiscated and looted art that would also permit investigations into artworks from colonial contexts.47

Over the past ten years, the Kunstmuseum Bern has galvanized the art world at home and abroad with the “Gurlitt Legacy”, a trove of about 1600 works.48 It is named after German collector Hildebrand Gurlitt (1896–1956), who was directly involved in “cleansing” museums of artworks regarded as “degenerate” and in looting art under the Nazi regime in the 1930s. His son, Cornelius Gurlitt, recently made a wholly unexpected donation of this entire hoard to Bern. What to do with such a Greek gift? After some hesitation, the museum expressed its determination to investigate the origins of the trove in compliance with the Washington Principles. It was the first Swiss art museum to set up a department for provenance research. In an exemplary and transparent fashion, each item in the vast collection was classified according to a traffic light rating system that identified unambiguous restitution cases, revealed gaps in information, and left “room for the unexplained” – always with the express intention of not exhibiting any works suspected of having been acquired by violent or coercive means. New methods and standards of provenance research were developed over the course of this mammoth undertaking, and the results were presented at three exhibitions: “Entartete Kunst – beschlagnahmt und verkauft” (2017), “Der NS-Kunstraub und die Folgen” (2018) and “Gurlitt. Eine Bilanz” (2022/23). The Bern museum’s open-ended and unbiased approach went down well with the public and the experts alike: in reversing the burden of proof to the museum’s disadvantage, it not only took a new ethical stance, but also showed a way out of the complicit secrecy prevalent in so many public institutions.

The Kunstmuseum Basel proceeded in a similar way with the works in the “Glaser Collection,” which had been expropriated and exploited by the National Socialists, and various modernist paintings acquired from the Third Reich’s vast stocks of “degenerate art” beginning in 1939. Two parallel exhibitions, Zerrissene Moderne. Die Basler Ankäufe “entarteter Kunst”49 and Die Sammlung Curt Glaser50 (2022-2023), have provided a look at the current state of provenance research, and the Glaser exhibition itself formed part of a “fair and equitable settlement” with the Glaser family.

Special exhibition at Museum Wallraf-Richartz: “Von Dürer bis Van Gogh-Sammlung Bührle trifft Wallraf (From Dürer to van Gogh – the Bührle Collection meets Wallraf).”

Persistence and change in Zurich, mixed prospects for Switzerland

In Zurich, on the other hand, the entrenched defensive position was at first reinforced. The Bührle Foundation, which had rediscovered the collection’s documentation archive in 2010, assumed that the entire collection was “clean” despite all the evidence to the contrary. This dismissive attitude now came under increasing pressure. In the fall of 2022, the city and canton of Zurich and the Kunsthaus convened a “round table” to come up with a viable solution. In mid-March 2023, Philipp Hildebrandt, a former Swiss National Bank president and vice chairman (since 2012) of the BlackRock investment company as well as being the new president of the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft, and Belgian literary scholar and art critic Ann Demeester, the new director of the Kunsthaus, announced that experts would look into the history of about two hundred paintings and sculptures from the museum’s collection. In accordance with the round table’s proposal, historian Raphael Gross, currently the director of the German Historical Museum in Berlin, has now been officially entrusted with checking the provenance of the Bührle artworks and is to submit his report on this very first thorough investigation next year.51

The Kunsthaus, for its part, decided to take advantage of the terms of the new loan agreement concluded with the private Bührle Foundation in early 2022 in order to open a new exhibition of the Emil Bührle Collection in November 2023, even before the completion of Gross’s report. The 120 most important works are now arranged “by chronology of acquisition” in a show entitled “The Bührle Collection: A Future for the Past. Art, Context, War and Conflict.”52 Far more information is now provided about Nazi looting and the provenance of the contentious paintings, but there is still far too little consideration of the “decades-long entanglement between the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft, the association behind the Kunsthaus Zürich, and Emil Bührle.”53 The whole advisory board for this new exhibition resigned a week before the opening over its failure to adequately present the victims’ side of the story. The new Kunsthaus director Ann Demeester riposted that this was merely an interim stage in the process of coming to grips with the past, a process that is by no means complete.

For all its obvious shortcomings, the new exhibition does mark a significant change in the handling of the historically fraught Bührle Collection. But it raises the question of who is to pay for the cost of the ongoing inquiries. If the Kunsthaus is showing the paintings, it has a responsibility to provide funding for serious provenance research. In order to prevent the costs from being defrayed by the public while the profits line private pockets, a formal donation of the Bührle Collection to the Kunsthaus Zürich would be the best solution.54 It also solves another problem, for the current ownership situation leaves open the question of who is to decide what to do about contentious restitution claims. The Kunsthaus, as a signatory to the Washington Agreement, is bound by international law to participate in “just and fair solutions”. But that does not apply to the current owner, the Bührle Foundation.

Museums, which have a responsibility to the public, must also be accorded autonomy in decisions regarding how to handle artworks. This goes without saying for other Zurich museums, too. The Museum Rietberg is a poignant case in point, for it was founded in 1952 with a donation from Nazi banker (and one-time Nazi party member) Eduard von der Heydt, who was a big collector of “non-European” art (especially from China and India), i.e. works that were also acquired under exploitative colonial circumstances and may well present restitution issues – this remains to be cleared up in a transparent manner.55

As far as the Bührle Collection is concerned, we’ve been witnessing a remarkable coincidence lately. Just as the Kunsthaus Zürich was “opening up its dark chambers”56 and controversy over the Bührle Collection was coming to a head, Credit Suisse, a key player in the cultural sponsorship, spiraled into a crisis of confidence. It should be recalled that the presidents of the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft from 1922 to 1940 and then again from 1987 to 2021 all came from Credit Suisse.57 Just a year after the crisis set in, a raft of scandals that had dragged on for over ten years, attended by a precipitous drop in stock market prices, all ground to a halt. On March 19, 2023, the fate of Credit Suisse was sealed. This venerable old institution, founded in Zurich back in 1856, which had long been the flagship of international finance in Zurich, ceased to exist. It was taken over by its rival, UBS – with substantial risks take on by the state. This spectacular collapse is also the result of a deep crisis of the free-market economics that have had such a formative influence on the history of the Swiss Confederation. The representatives of the art-and-capital complex who used to set the tone and pace of elite Zurich society have now suffered a double debacle. Their Bührle smokescreen scheme at the Kunsthaus has blown up in their faces, only to be followed by the loss of their most important bank.

Zurich, the Swiss economic powerhouse, and with it the whole nation, have come to realize once again that the choice is simple: learn from past mistakes or go under. As for the Kunsthaus and its handling of the historically contaminated Bührle Collection, there is some hope that the ongoing learning process will bear fruit. But it won’t make the art world’s problems go away. It has long been clear to experts that the thorniest complications now lie not in the public sector, but in the world of private art dealing. Since the 1980s, works of art, especially paintings, have increasingly become investments that are legally configured through trusts and shell companies to take advantage of tax breaks.58 They serve HNWIs (high-net-worth individuals) not only as stores of value, but also for purposes of transnationally integrated financial management. Although Switzerland was forced by the US and the OECD to join in the fight against tax evasion after 2009, there is good reason to suspect that it remains a hub of the global art trade used for tax avoidance by the ultra-rich.59

With its coarse-meshed free-market regulatory regime and its freeports (high-security extraterritorial duty-free zones) in Geneva, Zurich and Basel, this neutral country provides a global platform for dubious and illegal transactions. Wars and failed states as well have led to an influx not only of weapons, but also of artworks. The “antiquities trade” encompasses a wide variety of precious objects, many of which are deposited in a freeport, whence they can be transferred easily and unobserved. And yet the Swiss government sees no need for intervention there. This could pose a future political risk because the guaranteed discretion of the past has been compromised lately by critical reporting in the press. It is also foreseeable that other countries will no longer accept the special exemptions that Switzerland has claimed and enjoyed so far.

Over the past ten years, a spate of scandals and court cases have exposed a number of families and companies’ business strategies based on secrecy and confidentiality. The operations of the Mugrabi and Nahmad families, for example, which are both organized as companies and have large art collections, were brought to light in 2013.60 The Nahmads own over three thousand Impressionist and modern artworks (worth as much as $5 billion), most of which are – or until very recently, were – stored in a bonded warehouse near Geneva.61 A case has now been reopened in France against the Wildenstein dynasty, who have been active in the art trade since 1870 and have relied on absolute discretion as a recipe for success over the course of many generations. The public prosecutor has called their business a “criminal enterprise” engaged in the “longest and most sophisticated tax fraud” in modern French history.62 It comes as little surprise that Swiss freeports and banks are also involved in this international case. Whether in Switzerland or elsewhere around the globe, the art world is going to keep making headlines.

Notes

1

Officially the “Sammlung Emil Bührle,” owned by the Stiftung Sammlung Emil G. Bührle registered in Zurich, hereinafter referred to respectively as the “Bührle Collection” and “Bührle Foundation”.

2

Catherine Hickley, “A Nazi Legacy Haunts a Museum’s New Galleries,” The New York Times, Oct. 11, 2021.

3

Erich Keller, Das kontaminierte Museum. Das Kunsthaus Zürich und die Sammlung Bührle, Zurich, Rotpunkt Verlag, 2021.

4

Catherine Hickley, “A Nazi Legacy Haunts a Museum’s New Galleries,” The New York Times, Oct. 11, 2021.

5

Etienne Dumont, “La Collection Emil G. Bührle crée de nouveaux remous à Zurich,” Le Bilan, Nov. 15, 2021.

6

Thomas Ribi, “Hat die Stiftung Bührle gelogen? Mitglieder der Bergier-Kommission kritisieren, ihnen seien Akten vorenthalten worden,” nzz.ch, Nov. 09, 2021.

7

Lukas Gloor (ed.), Die Sammlung Emil Bührle: Geschichte, Gesamtkatalog und 70 Meisterwerke, Munich, Hirmer, 2021, p. 9.

8

Lukas Gloor (ed.), Die Sammlung Emil Bührle: Geschichte, Gesamtkatalog und 70 Meisterwerke, Munich, Hirmer, 2021, p. 233, 235.

9

Daniele Muscionico, “Die Bombe Bührle tickt überall – Künstler auf der ganzen Welt fordern wegen umstrittener Politik ihre Werke zurück,” Tagblatt, Jan. 28, 2022.

10

Christoph Heim, “Es reicht jetzt, Herr Becker! Übergeben Sie das Zepter an Ann Demeester!” Tagesanzeiger, Jan. 2, 2022.

11

Lehrstuhl Leimgruber, Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus. Die Entstehung der Sammlung Emil Bührle im historischen Kontext, Zurich, buch & netz, 2021. The first version of this study itself became a subject of controversy. See the two expert reviews commissioned by the University of Zurich and published in late 2021. Lehrstuhl Leimgruber’s personal page: www.fsw.uzh.ch/de/personenaz/lehrstuhlleimgruber

12

Heinz Nigg, entrechtet – beraubt – erinnert: Dokumentation über Opfer des Nationalsozialismus mit Bezug zu Zürich, Zurich, Edition 8, 2021. Video: remembered.ch/

13

Lehrstuhl Leimgruber’s personal page: www.fsw.uzh.ch/de/personenaz/lehrstuhlleimgruber

14

The Flick Collection was exhibited at Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin in 2004. Cf. Peter Kessen, Von der Kunst des Erbens: Die “Flick-Collection” und die Berliner Republik, Berlin, Philo Verlag, 2004; Thomas Ramge, Die Flicks. Eine deutsche Familiengeschichte um Geld, Macht und Politik, Frankfurt am Main, Campus Verlag, 2004.

15

Lehrstuhl Leimgruber, Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus. Die Entstehung der Sammlung Emil Bührle im historischen Kontext, Zurich, buch & netz, 2021, p. 149, Fig. 4; p. 173, Fig. 5.

16

Adolf Jöhr, head of Credit Suisse (formerly Schweizerische Kreditanstalt), served as president of the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft from 1922 to 1940. He was also a prominent figure in the Swiss electric power industry. See: Stéphanie Ginalski et al., Art, finance, and elite networks. The Presidents of the Zurich Art Society (Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft), 1890-2021, working paper, Lausanne & Zurich, May 2021.

17

“Grösster Kunstraub der Schweizer Geschichte,” Swissinfo.ch, Feb. 11, 2008. Four years later, the Bührle Foundation was able to announce that the paintings were back in its possession. This repossession was the result of a crafty undercover maneuver, in the course of which €1.4 million was handed over to the thieves as a down payment on the ransom, which has yet to be recovered. See: Alois Feusi, “Der Raubüberfall auf die Sammlung Bührle hallt noch immer nach,” nzz.ch, Feb. 09, 2018.

18

The left-wing “Alternative Liste” also voted “no”.

19

Thomas Buomberger and Guido Magnaguagno (eds.), Schwarzbuch Bührle: Raubkunst für das Kunsthaus Zürich?, Zurich, Rotpunktverlag, 2015.

20

Dölf Duttweiler et al., Die Bührle-Saga: Festschrift für einen Waffenindustriellen, der zum selbstlosen Kunstmäzen wurde, Zurich, Limmat Verlag, 2021 [1981].

21

See his crucial study: Thomas Buomberger, Raubkunst – Kunstraub: die Schweiz und der Handel mit gestohlenen Kulturgütern zur Zeit des Zweiten Weltkriegs, Zurich, Orell Füssli Verlag, 1998.

22

Peter Hug, Schweizerische Rüstungsindustrie und Kriegsmaterialhandel zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (2 Vol.), Zurich, Chronos Verlag 2002; Marc Perrenoud et al., La place financière et les banques suisses à l’époque du national-socialisme: Les relations des grandes banques avec l’Allemagne (1931-1946), Lausanne/Zurich, Payot/Chronos, 2002; Esther Tisa Francini, Anja Heuss, and Georg Kreis, Fluchtgut – Raubgut. Der Transfer von Kulturgütern in und über die Schweiz 1933–1945 und die Frage der Restitution, Zurich, Chronos Verlag, 2001.

23

Peter Hug, Schweizerische Rüstungsindustrie und Kriegsmaterialhandel zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (2 Vol.), Zurich, Chronos Verlag, 2002; Lehrstuhl Leimgruber, Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus. Die Entstehung der Sammlung Emil Bührle im historischen Kontext, Zurich, buch & netz, 2021, Ch. 1, “Transformationen”, pp. 33-106.

24

Yves Demuth, Schweizer Zwangsarbeiterinnen: Eine unerzählte Geschichte der Nachkriegszeit, Zurich, Beobachter-Edition, 2023.

25

Jakob Tanner, “Heimsuchungen am Heimplatz. Wie der Waffenfabrikant Emil G. Bührle in Zürich Kulturpolitik betrieb,” Geschichte der Gegenwart, Sept. 15, 2021.

26

Lehrstuhl Leimgruber, Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus. Die Entstehung der Sammlung Emil Bührle im historischen Kontext, Zurich, buch & netz, 2021, Ch. 3, “Translokationen”, pp. 197-255.

27

Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War, Switzerland, National Socialism and the Second World War. Final Report, Pendo Editions, Zurich, 2002.

28

This is the assumption underlying the study: Lehrstuhl Leimgruber, Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus. Die Entstehung der Sammlung Emil Bührle im historischen Kontext, Zurich, buch & netz, 2021.

29

Militärregierung – Deutschland Kontrollgebiet des 0bersten Befehlshabers, Gesetz No. 52 Sperre und Beaufsichtigung von Vermögen.

30

Peter Mosimann, “‘Ist die Schweiz ein Paradies für Raubkunst?’ Interview with Yves Kugelmann,” Tachles, May 13, 2022, pp. 18-20, here p. 20.

31

Natan Sznaider, Fluchtpunkte der Erinnerung. Über die Gegenwart von Holocaust und Kolonialismus, Frankfurt am Main, Hanser, 2022, pp. 58-60, here: p. 60.

32

For an overview, see: Peter Mosimann, Marc-André Renold, and Andrea F.G. Raschèr, Kultur, Kunst, Recht. Schweizerisches und internationales Recht, Basel, Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 2020.

33

Kurt Siehr, “Rechtsfragen zum Handel mit geraubten Kulturgütern in den Jahren 1933-1950,” in Daniel Thürer and Frank Haldemann (eds.), Die Schweiz, der Nationalsozialismus und das Recht. Vol 2. Privatrecht (ICE-Juridical Contributions No. 19), Zurich, 2001, pp. 125-203, here p. 148.

34

Kurt Siehr, “Rechtsfragen zum Handel mit geraubten Kulturgütern in den Jahren 1933-1950,” in Daniel Thürer and Frank Haldemann (eds.), Die Schweiz, der Nationalsozialismus und das Recht. Vol 2. Privatrecht (ICE-Juridical Contributions No. 19), Zurich, 2001, pp. 125-203, here p. 146.

35

Kurt Siehr, “Rechtsfragen zum Handel mit geraubten Kulturgütern in den Jahren 1933-1950,” in Daniel Thürer and Frank Haldemann (eds.), Die Schweiz, der Nationalsozialismus und das Recht. Vol 2. Privatrecht (ICE-Juridical Contributions No. 19), Zurich, 2001, pp. 125-203, here p. 146 and 183.

36

Greta R. Krippner, “The Financialization of the American Economy,” Socio-Economic Review, vol. 3, 2005, p. 173-208. Luc Boltanski and Éve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, London, Verso, 2018; Thomas Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2013.

37

Luc Boltanski and Arnaud Esquerre, Enrichissement: Une critique de la marchandise, Paris, Gallimard, 2017.

38

Philip Ursprung, Die Kunst der Gegenwart. 1960 bis heute, Munich, Beck, 2019, p.105; see also: Peter Watson, From Manet to Manhattan: The Rise of the Modern Art Market, New York, Random House, 1992; Julie Metzdorf, “Kunst und Profit – Über den Kunstmarkt,” radioWissen, July 5, 2022.

39

Luc Boltanski and Arnaud Esquerre, Enrichissement: Une critique de la marchandise, Paris, Gallimard, 2017.

40

Articles that address this problem can be found in: Bertrand Forclaz et al. (eds.), “Collectionner comme pratique,” Traverse, Zeitschrift für Geschichte, vol. 19, n° 3, 2012, pp. 17-124; and in: Sébastien Guex and Chantal Lafontant Vallotton (eds.), “Der Schweizer Kunstmarkt (19.-20. Jahrhundert),” Traverse, Zeitschrift für Geschichte, vol. 9, n° 1, 2002, pp. 7-177.

41

Elazar Barkan, The Guilt of Nations: Restitution and Negotiating Historical Injustices, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001; Jakob Tanner, “Memory, Money, and Law. How to Come to Terms with the Injustices and Atrocities of the Second World War,” in Mô Bleeker and Jonathan Sisson (eds.), Dealing with the Past. Critical Issues, Lessons Learned, and Challenges for Future Swiss Policy, Bern, SwissPeace, 2004, pp. 77-87.

42

Esther Tisa Francini, Anja Heuss, and Georg Kreis, Fluchtgut – Raubgut. Der Transfer von Kulturgütern in und über die Schweiz 1933-1945 und die Frage der Restitution, Zurich, Chronos Verlag, 2001.

43

This exhibition was a stop on a tour that included the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Montreal, the Yokohama Museum of Art, and the Royal Academy of Arts in London, as well as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in 1990-1991.

44

Michael Kimmelman, “Was This Exhibition Necessary?” The New York Times, May 20, 1990.

45

Barbara Bonhage, Hanspeter Lussy, and Marc Perrenoud, Nachrichtenlose Vermögen bei Schweizer Banken. Depots, Konten und Safes von Opfern des nationalsozialistischen Regimes und Restitutionsprobleme in der Nachkriegszeit, Zurich, Chronos, 2002.

46

Andrea Raschèr, “Washingtoner Raubkunst-Richtlinien – Entstehung, Inhalt und Anwendung,” Kunst und Recht, vol. 11, n° 3-4, 2009, pp: 75-79.

47

Jon Pult, Unabhängige Kommission für NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogene Kulturgüter, Motion submitted to Swiss National Council, Dec. 09, 2021. The debate on the translocation of artworks in a colonial context cannot be addressed here. Cf: Bénédicte Savoy, Beutekunst: Eine Geschichte des Kunstraubs von der Antike bis heute, Munich, Beck Verlag, 2018.

48

See: Kunstmuseum Bern (ed.), Gurlitt. Eine Bilanz, Exhibition brochure, Bern, 2022.

51

Regionaljournal Zürich Schaffhausen, “Kunsthaus Zürich verkündet neue Strategie für Provenienzforschung,” Sfr.ch, March 14, 2023. While the commissioners of this study assume that the investigations are to be confined to the period before 1945, they clearly need to cover the first post-war decade, too, as noted above.

54

Jakob Tanner, “‘Die beste Lösung wäre eine Schenkung’. Zur historischen Einordnung der Bührle-Sammlung im Zürcher Kunsthaus,” NZZ am Sonntag, Feb. 27, 2022, pp. 52-53; Jakob Tanner and Jacques Picard, “Die Bührle-Sammlung sollte dem Kunsthaus geschenkt werden,” Tagesanzeiger, Nov. 16, 2023, p. 27.

55

In the current exhibition “Pathways of Art: How Objects Get to the Museum,” the Museum Rietberg seeks to document its provenance research efforts for the public.

56

Gisela Blau, “Kunsthaus Zürich öffnet die Dunkelkammern,” Tachles, vol. 17, 2023, p. 4.

57

Lehrstuhl Leimgruber, Kriegsgeschäfte, Kapital und Kunsthaus. Die Entstehung der Sammlung Emil Bührle im historischen Kontext, Zurich, buch & netz, 2021, Ch. 2, “Netzwerke,” pp. 107-196.

58

Still worth reading: Gabriel Zucman, La Richesse cachée des nations, Paris, Seuil, 2013; William Vlcek, Offshore Finance and Small States: Sovereignty, Size and Money, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

59

Solutions to this problem are proposed by: Marc Henzelin and Deborah Lechtman, “Le monde de l’art doit s’adapter à la lutte contre le blanchiment, la fraude fiscale et le terrorisme,” Not@Lex, vol. 75, 2015.

60

Stefan Eiselin, “Ein Playboy, ein Gangster und ein Schweizer Konto,” Handelszeitung, Apr. 19, 2013; Tim Ackermann, “Die überraschende Verletzlichkeit eines Halbgotts,” Welt, Feb. 3, 2013.

61

Olga Kronsteiner, “Warum ein von Trump begnadigter Kunsthändler kein Waisenknabe ist,” Der Standard, Jan. 30, 2021.

62

Rachel Corbett, “The Inheritance Case That Could Unravel an Art Dynasty,” The New York Times Magazine, Aug. 23, 2023.