What makes men and women from all over the world, of all ages, and sometimes very young, from extremely varied cultural and social backgrounds, rich and poor, the affluent and the oppressed, suddenly “tip” into unheard-of and hitherto unimaginable violence, in which killing their neighbor becomes their daily task? There is no shortage of recent examples. The genocidal violence that swept through Rwanda between April and July 1994 left over 800,000 Tutsis dead. They were methodically hunted down, rounded up, confined, and assassinated, by hundreds of Hutu men and women armed with machetes and rifles. Former neighbors, mostly, and even members of families tied by kinship, did not hesitate to kill those they had greeted but recently, or considered as their kin in the event of mixed couples. But despite having been close previously, nothing seemed able to end their assassinating fury1. In the main psychiatric hospital in Rwanda, in the suburb of Kigali, where Hutu and Tutsi care workers had hitherto displayed the same devotion to all of their patients, the selection was just as pitiless from the earliest days of the genocide. Tutsi patients and care workers were hounded, rounded up, and then assassinated by doctors, nurses, and auxiliaries who had suddenly turned killer2. This murderous violence continued for over one hundred days, without respite, from sunrise to sunset, and all night long. It raged indiscriminately against men, women, children, and the elderly, on the sole suspicion of being Tutsi. All, down to the very last one, had to die. No sanctuary could protect them. Churches, hospitals, and schools were turned into places of systematic slaughter. Some Tutsi women were spared, but the survivors were only allowed to live after being mutilated by atrocious sexual violence, indelibly marked by the deeds of the perpetrators3.

Jean Hatzfeld, Une saison de machettes, Paris, Le Seuil, 2003.

These killers, including a very large number of women involved in the massacres, had never killed anyone before. They were not even ideologues or former combatants4. None of them had received any theoretical or practical training. Massacring is not something you are taught; you pick it up as you go along. That, at least, is what most of the perpetrators say, who were themselves surprised at the number of victims they had personally “dealt with”, or in on words killed and disposed of5.

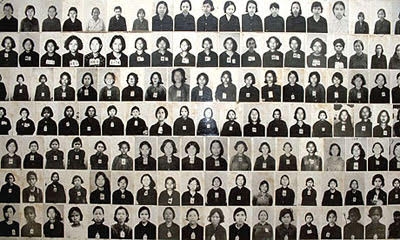

Two decades earlier in Cambodia, between April 1975 and December 1979, nearly 2 million people were assassinated by the Khmer Rouge regime. Young Khmers, often peasants and not necessarily brutes, methodically killed other defenseless Khmers by their tens and hundreds. It was a production line of death, which at times left the killers exhausted. The elimination of over one third of the population in four years is a macabre prowess, and still a source of pride for the country’s former leaders. Such as Duch – the head of the notorious S21 detention centre in Phnom Penh, where over 15,000 Cambodians were tortured and then executed – who proudly stated at his trial in 2010 that had the Khmer Rouge won, he would have been a hero, not a defendant obliged to appear before his judges6.

Photo portraits from the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Prisoners were photographed on arriving at S-21. Photo Krystel Maurice at: http://www.cambodgepost.com/4842-s-21-les-revelations-de-lenquete-menees-par-les-juges-dinstruction-ii/

Rithy Panh, books.

Despite the achievements of the ever swifter international justice system, and the at times severe sentences handed down against the main political leaders responsible for these massacres, the list of genocidal crimes only grows longer. Troops of the Islamic State Organization are currently conducting an unprecedented purge of their supposed opponents, and their relatives, in the territories they control, as attested by reports from survivors in recently liberated towns such as Mosul and Palmyra. The genocidal violence has spilled far out across the borders of these territories, seeking to spread throughout the entire Middle East, across Africa, Asia, Europe, and the United States. President Bashar al-Assad‘s regime in Syria does not even seek to conceal proof of its abuses. The gassing of the population, mass murders of civilians, and transformation of detention centers into extermination centers are the daily weapons of a degenerate regime, prepared to do anything to safeguard its survival7.

Unlike wars and other armed conflicts, it is a matter of killing without trial, and on industrial scale, very large numbers of unarmed civilians, men, women, elderly, children, and even babies, not for what they think or have done, but simply for what they are. Or more exactly, for what their persecutors say they are. And it is precisely this specificity which best captures the nature of genocidal violence. Since the Second World War there has been a profusion of legal, historical, sociological, political, anthropological, psychoanalytic, and philosophical scholarship on the topic. Originating in the United States, and now found in very many universities around the world, Genocide Studies is now a discipline in its own right, drawing scholars from many different horizons, using a necessarily multidisciplinary approach. Their sheer number means there is no room to cite the most important authors and currents of thought currently producing more detailed knowledge about the historical and socio-political processes leading to the introduction of extermination policies. This body of scholarship has progressively moved away from the restrictive legal framework – in which the notion of genocide originated in the work of Raphael Lemkin, in the final stages of the Second World War – and adopted a comparative approach to mass massacres8. In France Jacques Semelin was the first to lay down the groundwork for rigorous analysis of mass massacre. He based his work on a precise distinction between massacres seeking to dominate a population, in which the goal of mass killings is submission, and massacres seeking to completely and definitively eliminate them, in which the goal of the killings is to wipe a people out9.

Despite analysis of the historical and political conditions, despite insights into the role played by indoctrination and ideology, despite the bringing to light of pre-existent ferocious racism and antagonisms, despite the minute study of chains of command linking all the protagonists’ acts and decisions, from those giving the orders through those finally executing them – despite all this, the crucial issue of mass killers’ motivation and conscience often goes unaddressed. Who are these men and women who become mass killers? How do they tip into horror, to the extent that it becomes their daily life? Is there not an inner force in each of us which would prevent any supposedly “normally constituted” person from killing defenseless innocents?

We could explore at length the various theoretical ideas that have sought to explain how ordinary people can become mass killers depending upon the circumstances10. The idea of the banality of evil was first introduced by Hannah Arendt, to emphasize the odiously ordinary nature of these killers and of those giving the orders11. It has been taken up and developed in much subsequent research about mass killers. Whether it be the minute description of members of the 101st reserve battalion of the German police involved in directly assassinating over 35,000 Jewish men, women, elderly, and children, or psycho-sociological theorizings about the executioners of the Third Reich, this scholarship backs up Arendt’s horrifying observation, and confirms the stupefying complicity of banally ordinary people slipping towards mass murder12. Nevertheless, none of these approaches manages to resolve the unfathomable enigma of the conscience of murderers.

Adolf Eichmann, April 1961, Jerusalem.

Yet rather than these works of scholarship, which are often unknown to the general public, it is no doubt film and theater that has done the most to lend a face to the banality of evil, and endow these anonymous killers with an inner psyche. It is by staging the act of those who are going to or have already killed, and especially by seeking to access their inner world, that we can sometimes imagine them, and even wonder what we would have done in their position13. Both theater and cinema pull off the incredible performance of allowing us to watch on, powerless, as an ordinary man turns killer. The most frequently encountered and often most frightening figure – the most common figure in the history of classical theatre and in contemporary cinema – is no doubt not the most faithful representation. I believe that the powerful dramatic device in which a mass killer is depicted as a man grappling with himself in painful inner combat, before his conscience is defeated and he gives himself over to his basest instincts is, in fact, misleading. Things are often a lot simpler. Perversion does not always have to reign. This, however, is what certain works have sought to suggest, instilling the figure of the pervert in the contemporary imaginary as the archetypal bloodthirsty executioner.

Luchino Visconti’s famous 1969 film, The Damned, was an acclaimed hit. It was the culmination of Western introspection into how barbarity can reappear at the heart of the civilization process. It offered a frightening metaphor for the rise of Nazism through the decadence of a wealthy German family. The central theme links the Nazi rise to power with the progressive animation of all of the protagonists’ most perverse instincts, corrupting each member of the family. For the 2016 Avignon Festival, the Belgian director Ivo Van Hove took Visconti’s scenario and staged an even more disturbing version in the great courtyard of the Palais des Papes. Beyond the questioning of Nazism, all contemporary barbarities were denounced. This immediately echoed with the terrifying current events of 2016, made up of murderous attacks and major political change. It referenced the rise of all forms of extremism, where the glorification of hatred of the other prepares to reign undisputed over once democratic lands. The spectators felt the poison of perversion coursing through their bodies, slowly infiltrating each and every one, up until the final scene when they found themselves in the sights of the killers.

Les damnés, Luchino Visconti, film, 1969.

The press rightly reacted by unanimously hailing the event, described as “a shock” in Télérama, “a monster of a play” that was “mind-blowing and disturbing” for Le Figaro, with Le Monde evoking the “demented and demoniac” unveiling of “humanity’s atrocious aptitude for barbarity”. They all agreed on the quality of the performance by the director and the actors from the Comédie Française, including those who normally condemn theatrical display and this sort of brutality. Many commented on the feeling of unease at such voyeurism, imposed by the director on the spectators. Yet Ivo Van Hove was universally credited with having managed to bring to life this terrifying plunge into barbarity, played out in front of a stunned audience. Nothing was overlooked. Perversion, incest, decadence, ignominy, greed, baseness, and the bloodiest and most bloodthirsty of murders were all paraded before the spectators. Bodies wallowed with morbid passion in blood and lust. It was as if nothing could halt this infernal descent, in which death – though unavoidable – no longer seemed the worst of fates, for the worst was already there, and had been since far earlier, since the first transgression.

Les Damnés, Ivo Van Hove, festival d'Avignon, 2016.

In Ivo Van Hove’s stage performance, as in Visconti’s film, the tipping point arrives very early on, at the moment of the first transgression, one might say. Whether it be the death of the patriarch or barely repressed incestuous desire, the theatricalization of this inaugural transgression presages the infernal developments in which everything, truly everything, becomes possible. In a state of horror, everything is permitted. The equation put forward is both simple and bloodcurdling. The first transgression liberates the most violent and unhealthy passions, paving the way to a climax of unbridled gratification in which the other is both the instrument and object of devastating hatred. A hatred that makes your blood run cold, and in which perverse delight becomes the driving force for an abomination that is all the more frightening for being authorized. “Who, in the absence of all sanctions and all reprisals, would turn their back on such gratification?” is the question each protagonist seems to be asking us. Still, the reason why this mise-en-abyme of the worst human passions terrifies and petrifies, the reason why the horror becomes so frighteningly palpable, is mainly because the filmmaker and stage director have both, in their own way, been able to depict irrepresentable genocidal destruction for the spectators. Both have transposed the advent of a totalitarian and genocidal order through the dual register of the decadence of civilization and the psyche of the vilest human passions. Yet even though the transposition is indeed striking, it is nevertheless fundamentally foreign to the reality and organization of mass crimes.

For the genocidal realm is not actually one where everything is possible – quite the contrary in fact. Everything is ordered and methodical. Productivity gains and improvements in working conditions are sought, to enable the killers to continue killing, and up their tempo. The entire process adheres to a perfectly well-established sequencing. From the selection of the victims to their rounding up and execution, and right down to the methodic management of the remains, that is to say their corpses, recuperated objects, and even valuables stripped from them. Nothing is left to chance. Nothing is left to individual decision, even less to the gratification of sadistic impulses that would ineluctably be dulled by repetition, thereby hampering productivity. Order alone prevails. All genocidal societies proceed thus, compartmentalizing populations, designating those who shall necessarily die, and those on the contrary who are to be protected14. Each compartment has its own rules. Everything is exactly not possible. Selection for the compartment of death is pitiless, but what happens on the threshold is of little import given the overriding matter of final destruction. Killing is forbidden in the other category, and liable to severe punishment. The only reason to authorize the killing of an individual who had hitherto been spared is their transfer from one compartment to the other, on the basis of imputed treachery.

The accounts of ordinary executioners all attest to this reality. Killing in large numbers requires a complex organization that cannot respond to individuals’ personal passions. Hence death has a resolutely different status for the executioners and the victims. For the victim it circumscribes their subjective horizon, whereas for the perpetrator it is an awkward residue to be managed15. These killers all say the same thing. Killing, to their eyes, is a lengthy process, starting the minute they encountered the genocidal order, and ending only after their intervention. They only took part on an occasional basis, they declare. They should not be held responsible. They were merely at the end of a long chain of destruction. Nothing more than that, they claim, with disconcerting conviction. It would be misguided to see this justification as some pathetic defense, seeking to dilute their killing in the overall chain of command. It would be equally misguided to reproduce the classic interpretation still frequently deployed today, that submission to authority and blind obedience sufficiently account for what they are telling us16. For far more simply, these men and women consider that giving a final bludgeon, pulling the trigger, or sticking a knife into a throat is so precise, rapid, and mechanical a gesture that it becomes insignificant, leaving no trace on their memory. They can live with it. Only the repetition of the gesture, to the point of exhaustion, would appear to leave any memory trace for these killers. That is not to say their memory was suspended, or their sensations anaesthetized. On the contrary, it is specifically the entire environment of killing – the smell, the cries, the bawling of their chiefs, the projections, the blood, the bodies to be carted off for burial, and finally the physical exhaustion – that fashioned their subjective experience of it. Death, or more exactly its residue, the dead body, only strikes them as a technical constraint to be deal with, together with the difficulty of managing its abundance. “A problem faced by all municipalities” as the head of the Phnom Penh S21, Duch, said at his trial by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. When asked about the reasons leading him to write the words “to be destroyed” at the bottom of the handwritten confessions, obtained from the detainees after days and days of torture, he unhesitatingly presented himself as a mere municipal manager in charge of the security and well-being of the populations placed under his responsibility. “To have a clean town, you have to look after the waste,” he added arrogantly. “Well amongst us, under the Khmer Rouge, there were men and women to be treated along with the waste, this particularity changed nothing in the logistical constraints of municipal waste management!”.

The hypothesis of an infernal descent into the depths of human perversion at least had the merit of offering us a glimmer of hope, the prospect that one day we would see these executioners give up out of exhaustion, fatigued by their gratification in tirelessly repeating the same sequence. The reality is ultimately far more terrifying, for far less exotic. Nobody wallows in lust, nobody quaffs the blood of their victims, nobody feels authorized to breach a moral barrier that would otherwise be forbidden. For the killers, once their victims belong to the destined to die compartment there are no barriers holding them back. Each morning they know they are going to go off killing again. Every evening they know that the following day will be identical. So they prepare themselves, they think about how to avoid getting blisters from pulling the trigger hours on end, or from wielding a heavy bludgeon. They discuss with their chiefs the best way to transport corpses, to manage the remains, that is to say the bodies, the objects, and to get through their day’s labor as quickly as possible before starting again the next morning.

These men and women, far removed from lust and perversity as theoretically portrayed by Luchino Visconti and Ivo Van Hove, go about their daily job in the most ordinary manner, even though there is nothing ordinary about it. And that is horror in its purest form. Is it ultimately possible to transpose the disconcerting banality characterizing ordinary executioners to the performing arts? The American filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer tried to rise to the challenge in his critically acclaimed film “The Act of Killing”17. Oppenheimer’s film combines documentary and fiction to reconstitute the massacre of more than 1 million political opponents in Indonesia in 1965. His is a bold approach, consisting in getting the perpetrators of the period to act out scenes of torture and massacre for the camera. Half a century after the facts these men unhesitatingly reproduced their gestures, terrorizing crowds, selecting victims, before then torturing and executing them. They knew they were being filmed, and reveled in hamming it up, dwelling at length on the torment they were inflicting on their victims, exaggerating their cruel facial expressions. The spectators are nauseated by everything about these men, untouched by the slightest remorse or stirrings of guilt. And what the thereby film loses in credibility it perhaps gains in dread. Clearly they are frightening and frightful. Clearly they fear neither human justice nor the discredit caused by their gesticulations. But can they nevertheless teach us something about how ordinary men are transformed into mass killers? Nothing could be less certain. They readily admit that they were all hoodlums and assassins before enrolling in the regime’s parallel police forces. They were recruited for their technical expertise, for that matter. Most of them continued killing after the events, working amongst various local mafias.

The Act of Killing, film de Joshua Oppenheimer, 2013.

Hence if these men can still take pride in their macabre prowess, with the same jubilation today as they felt at the moment of the facts, it is precisely because they have always been practicing killers. Joshua Oppenheimer’s film is thus an outstanding account of the impunity that still covers the abuse perpetrated by General Suharto’s regime and the brutes who committed these exactions. But it tells us nothing about the more frequent situations in which men and women, though far less staunch partisans than Suharto’s killers, still accepted to become the docile executors/executioners of an implacable killing machine. If the performing arts one day accept to account for and portray that reality, then they will no doubt need to do away with any theatricalization of the act of killing, so as to meticulously dissect the intimate conditions that make it possible.

Notes

1

Hélène Dumas, Le Génocide au village: le massacre des Tutsi du Rwanda, Paris, Le Seuil, 2014.

2

Magnifique Neza, La Double folie. Impact du génocide des Tutsis sur l’hôpital Neuropsychiatrique de Ndera au Rwanda, Masters dissertation, EHESS, 2016.

3

See in particular Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Une Initiation. Rwanda (1994-2016), Paris, Le Seuil, 2017 and Émilienne Mukansoro, Psychothérapie de groupe, Génocide et violences sexuelles. Accès à la parole et résilience au Rwanda, Paris, EHESS, 2016.

4

See the excellent documentary by Violaine Baraduc and Alexandre Westphal, À mots couverts, http://www.amotscouverts.embelliefilms.fr/

5

Jean Hatzfeld, Une saison de machettes, Paris, Le Seuil, 2003.

6

Richard Rechtman, “Reconstitution de la scène du crime. À propos de Duch, le maître des forges de l'enfer, de Rithy Panh”, Études. Revue de Culture Contemporaine, July-August 2011, available online at: https://www.revue-etudes.com/article/a-propos-de-duch-le-maitre-des-forges-de-l-enfer-reconstitution-de-la-scene-du-crime-13908

7

“Près de 13 000 détenus ont été tués dans une prison syrienne en cinq ans, selon Amnesty”, Amnesty International, report, Le Monde, February 7, 2017.

8

Raphaël Lemkin, Qu'est-ce qu'un génocide?, (1944, ed. La Rochelle), Éditions du Rocher 2008.

9

Jacques Semelin, Purifier et détruire. Usages politiques des massacres et génocides, Paris, Le Seuil, 2005.

10

Richard Rechtman, “Que ressentent les génocidaires lorsqu'ils tuent?”, in Jean Jacques Courtine (ed.) L’Histoire des émotions. Vol. 3: De la fin du XIXe siècle à nos jours, Paris, Seuil, 2017, forthcoming.

11

Hannah Arendt. Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil. Viking Press, 1963.

12

Christopher R Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York, HarperCollins, 1992.

13

On this topic see the bold fictional autobiographical essay by Pierre Bayard, Aurais-je été résistant ou bourreau? Paris, Le Seuil, 2013.

14

Abraham de Swaan, Diviser pour tuer. Les régimes génocidaires et leurs hommes de main, Paris, Le Seuil, 2016.

15

Richard Rechtman, “Faire mourir et ne pas laisser vivre. Remarques sur l'administration génocidaire de la mort”, Revue française de psychanalyse, vol. 80, n °1, p. 136-148, 2016.

16

For discussion of submission to authority, see Stanley Milgram, Soumission à l'autorité, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1974. For a critique of abusive use of Milgram’s experiment to account for the transformation of ordinary men into mass killers, see for instance Rechtman, op. cit, 2016.

17

Joshua Oppenheimer, The Act of Killing, Danish, Norwegian, British feature film, 2013.

Bibliographie

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann à Jérusalem. Rapport sur la banalité du mal, Paris, Gallimard, (1966) 2002.

Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Une Initiation. Rwanda (1994-2016), Paris, Le Seuil, 2017.

Pierre Bayard, Aurais-je été résistant ou bourreau?, Paris, Le Seuil, 2013.

Christopher R. Browning, Des hommes ordinaires. Le 101e bataillon de réserve de la police allemande et la solution finale en Pologne, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, (1992) 2006.

Hélène Dumas, Le Génocide au village: le massacre des Tutsis du Rwanda, Paris, Le Seuil, 2014.

Jean Hatzfeld, Une saison de machettes, Paris, Le Seuil, 2003.

Raphaël Lemkin, Qu'est-ce qu'un génocide?, (1944, ed. La Rochelle), Éditions du Rocher, 2008.

Stanley Milgram, Soumission à l'autorité, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1974.

Émilienne Mukansoro, Psychothérapie de groupe, Génocide et violences sexuelles. Accès à la parole et résilience au Rwanda, Paris, EHESS, 2016.

Magnifique Neza, La Double folie. Impact du génocide des Tutsis sur l’hôpital Neuropsychiatrique de Ndera au Rwanda, EHESS, 2016.

Richard Rechtman, “Que ressentent les génocidaires lorsqu'ils tuent?”, in J-J. Courtine (dir.), L’Histoire des émotions. Vol. 3: De la fin du XIXe siècle à nos jours, Paris, Le Seuil, 2017, forthcoming.

Richard Rechtman, “Faire mourir et ne pas laisser vivre. Remarques sur l'administration génocidaire de la mort”, Revue française de psychanalyse, vol. 80, n° 1, 2016, p. 136-148.

Richard Rechtman, “Reconstitution de la scène du crime. À propos de Duch, le maître des forges de l'enfer, de Rithy Panh”, Étvdes. Revue de Culture Contemporaine, 2011, p. 320-339.

Jacques Semelin, Purifier et détruire. Usages politiques des massacres et génocides, Paris, Le Seuil, 2005.

Abraham de Swaan, Diviser pour tuer. Les régimes génocidaires et leurs hommes de main, Paris, Le Seuil, 2016.

Harald Welzer, Les Exécuteurs. Des hommes normaux aux meurtriers de masse, Paris, Gallimard, (2005) 2007.